Payaya people

The Payaya were local indigenous people whose territory encompassed the area of present-day San Antonio, Texas. Spanish priests encountered their village when they established the Alamo Mission in San Antonio in 1718 and recorded converting them. They were a Coahuiltecan band and are the earliest recorded inhabitants of San Pedro Springs Park, the geographical area that became San Antonio.[1] They called their village Yanaguana. It was located next to the river which the Spanish named the San Antonio. Some historians believe the band referred to the river as Yanaguana, but the Spanish Franciscan priest Damián Massanet recorded this as the name of their village .[2][3]

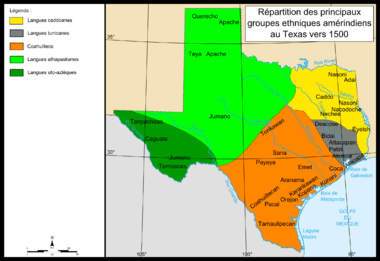

The Payaya (and Coahuiltecan) were a hunter-gatherer culture. The Spanish recorded their nut-gathering activities. Historians have speculated that the band's movements in the Edwards Plateau is an indication that pecans were a substantive diet source to the Payaya.[4] The band are known to have inhabited the areas of the San Antonio River, the Frio River to the west, and Milam County to the east, where they lived among the Tonkawa. By the year 1706, the Spanish had converted some Payaya among the indigenous converts baptized at Mission San Francisco Solano, 5 miles (8.0 km) from the Rio Grande in Coahuila, Mexico. Today's municipality of Guerrero is the approximate location of Mission San Francisco Solano.[5][6] The Payaya were a small band of sixty families by 1709.[7]

The Spanish first encountered them in the 17th century and counted ten different encampments.[8] Spanish Franciscan priest Damián Massanet wrote his impressions of the Payaya in the June 13, 1691 entry to his diary. He described an indigenous people who were friendly toward the Spanish, but warlike and combative within their own group. Massanet described a tribal war dance, deerskin clothing, and practice of stealing horses and women from other groups. He said the Payaya were adept at learning the Spanish language, and had a fondness for Spanish clothing.[9] He portrayed the Payaya as having a respectful attitude towards a higher spiritual power, and noted they had erected a wooden cross in their village. Massanet recounted that the day after the Spanish arrived, he and his group observed the Feast of Corpus Christi with a Mass, during which the Payaya were present.[10]

In 1716, the Payaya befriended Franciscan priest Antonio de Olivares. They became the mission Indians at San Antonio de Valero Mission, later known as the Alamo Mission in San Antonio.[11] The mission began assimilation of the Payaya by teaching them Spanish, and trade skills. The tribe had an elected form of self-government within the mission. In the latter half of the 18th century, infectious diseases took a high toll of the mission Payaya.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ "NRHP-THC San Pedro Springs Park". Texas Historical Commission. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ↑ Federal Writers Project (1940). Texas: A Guide to the Lone Star State. Hastings House. p. 327. ISBN 978-0-403-02192-5.

- ↑ "San Pedro Springs Park". Texas Historical Commission. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ↑ "Who Were the "Coahuiltecans"?". Texas Beyond History. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- ↑ Campbell, Thomas N. "Payaya Indians". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ↑ Weddle, Robert S. "San Francisco Solano Mission". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ↑ Anderson, Gary Clayton (1999). The Indian Southwest, 1580–1830: Ethnogenesis and Reinvention. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8061-3111-5.

- ↑ "Coahuiltecan Indians". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Commission. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ↑ Guerra, Mary Ann Noonan. "Indians of the San Antonio River: Yanaguana". University of the Incarnate Word. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- ↑ Matovina, Timothy (2005). Guadalupe and Her Faithful: Latino Catholics in San Antonio, from Colonial Origins to the Present. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8018-7959-3.

- 1 2 De Zavala, Adina; Flores, Richard R (1996). History and Legends of the Alamo and Other Missions in and Around San Antonio. Arte Publico Press. pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-1-55885-181-8.