Patricio Aylwin

| Patricio Aylwin | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| 30th President of Chile | |

|

In office 11 March 1990 – 11 March 1994 | |

| Preceded by | Augusto Pinochet Ugarte |

| Succeeded by | Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle |

| President of the Senate of Chile | |

|

In office 12 January 1971 – 22 May 1972 | |

| Preceded by | Tomás Pablo Elorza |

| Succeeded by | José Ignacio Palma Vicuña |

| Senator of the Republic of Chile for the Sixth Provincial Grouping Curicó, Talca, Linares y Maule | |

|

In office 15 May 1965 – 11 September 1973 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Patricio Aylwin Azócar 26 November 1918 Viña del Mar, Chile |

| Died |

19 April 2016 (aged 97) Santiago, Chile |

| Resting place |

Cementerio General de Santiago Santiago, Chile |

| Nationality | Chilean |

| Political party | Christian Democratic Party |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children |

Mariana Isabel Miguel José Antonio Juan Francisco |

| Alma mater | University of Chile |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Signature |

|

Patricio Aylwin Azócar (Spanish pronunciation: [paˈtɾisjo ˈelwin aˈsokaɾ] (![]()

Early life

Aylwin, the eldest of the five children of Miguel Aylwin and Laura Azócar, was born in Viña del Mar. An excellent student, he enrolled in the Law School of the University of Chile where he became a lawyer, with the highest distinction, in 1943. He served as professor of administrative law, first at the University of Chile (1946–1967) and also at the School of Law of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile (1952–1960). He was also professor of civic education and political economy at the National Institute (1946–1963).[2]

His brother Andrés was also a politician.[3]

On 29 September 1948, he was married to Leonor Oyarzún Ivanovic. They had five children (his daughter Mariana worked as a minister in subsequent governments) and 14 grandchildren (among them, popular telenovela and film actress Paz Bascuñán).[4]

Political career

Patricio Aylwin’s involvement in politics started in 1945, when he joined the Falange Nacional. Later he was elected president of the Falange in 1950 and 1951.[5][6] When that party became the Christian Democratic Party of Chile, he served seven terms as its president between 1958 and 1989.

In 1965 he was elected to the National Congress as a Senator. In 1971, he became the president of the Senate. During the government of Popular Unity, headed by Salvador Allende, he was also the president of his party, and he led the democratic opposition to Allende within and without Congress.[7] He is credited, to some degree, with trying to find a peaceful solution to the country’s political crisis. Distrusting Allende, Aylwin "demanded that the president appoint only military men to his cabinet as proof of his honest intent," which Allende did only partially, and Aylwin "apparently sided with pro-coup forces, believing that the military would restore democracy to the nation."[8]

He declared after the coup on Chilean National Television: "We have the conviction, of which, the call Chilean Road of conduction of socialism, which was pushed and hoisted like a flag for the Popular Unity, and exhibited much abroad, it was fully failed, and that knew the militants of the Popular Unity and Allende knew it, and for that reason they prepared themselves through the organization of armed military services, very strongly equipped that constituted a true parallel army, to give a self-coup and to assume by the violence the totality of the power, about those circumstances, we thought that the action of the Armed Forces simply was anticipated to that risk, to save to the country to fall in to a civil war or in a communist tyranny."

Aylwin was president of the Christian Democrats until 1976, and after the death of the party's leader, Eduardo Frei, in 1982, he led his party during the military dictatorship. Later he helped establish the Constitutional Studies Group of 24 to reunite the country's democratic sectors against the dictatorship. In 1979 he served as a spokesman in the group that opposed the plebiscite that approved a new constitution.

In 1982 Aylwin was elected vice president of the Christian Democrats. He was among the first to advocate acceptance of the Constitution as a reality in order to facilitate the return to democracy. The opposition eventually met the legal standards imposed by the Pinochet regime and participated in the 1988 plebiscite.

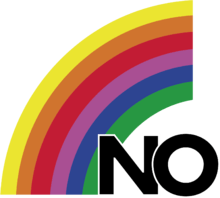

On 5 October 1988, the Chilean national plebiscite was held. A "Yes" vote would grant Pinochet eight more years as president. Despite the widespread expectation that Pinochet would be voted an extended term, the "No" campaign triumphed, in part because of a superb media campaign depicted in the 2012 film No. Patricio Aylwin was at the center of the movement that defeated General Pinochet.[9] After the plebiscite, he participated in negotiations that led the government and the opposition to agree on 54 constitutional reforms, thereby making possible a peaceful transition from 16 years of dictatorship to democracy.

Presidency

.jpg)

Patricio Aylwin was elected president of the Republic on 14 December 1989.

Although Chile had officially become a democracy, the Chilean military remained highly powerful during the presidency of Aylwin, and the Constitution ensured the continued influence of Pinochet and his commanders, which prevented his government from achieving many of the goals it had set, such as the restructuring of the Constitutional Court and the reduction of Pinochet's political power. His administration, however, initiated direct municipal elections, the first of which were held in June 1992. In spite of the severe limits imposed on Aylwin's government by the Constitution, over four years, it "altered power relations in its favor in the state, in civil society, and in political society."[10] Pinochet was determined that the military not be punished for its role in overthrowing Allende's government or for the years of military dictatorship. Aylwin did attempt to bring to justice those in the military who committed abuses.[11]

The Aylwin Government did much to reduce poverty and inequality during its time in office. A tax reform was introduced in 1990 which boosted tax revenues by around 15% and enabled the Aylwin Government to increase government spending on social programs from 9.9% to 11.7% of GDP. By the end of the Aylwin government, unprecedented resources were being allocated to social programs, including an expanded public health programs, vocational and training programs for young Chileans, and a major public housing initiative.[12]

A new Solidarity and Social Investment Fund was set up to direct aid towards poorer communities, and social spending (especially on health and education) increased by around one-third between 1989 and 1993. A new labor law was also enacted in 1990, which expanded trade union rights and collective bargaining[13] while also improving severance pay for workers.[14] The minimum wage was also increased,[15] as were family allowances, pensions, and other benefits.[16] Between 1990 and 1993, real wages grew by 4.6%, while the unemployment rate fell from 7.8% to 6.5%. Spending on education increased by 40% while spending on health increased by 54%.[17] The incomes of poor Chileans increased by 20% in real terms (above the rate of inflation) under the Aylwin Government, while increases to the minimum wage meant that it was 36% higher in real terms in 1993 than in 1990. A slum clearance program was also initiated, with over 100,000 new homes built under the Aylwin Government, compared with 40,000 per annum under the Pinochet Government.[18]

Under the Aylwin government, the numbers of Chileans living in poverty significantly decreased, with a United Nations report estimating that the percentage of the population living in poverty had fallen from around 40% of the population in 1989 to around 33% by 1993.[13]

He was succeeded in 1994 by the election of Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle, the son of the late President Eduardo Frei.

Later life

After leaving office in 1994, he continued his lifelong commitment to promoting justice. In 1995, he was the catalyst for a United Nations summit on poverty. He was president of the Corporation for Democracy and Justice, a non-profit organization he founded to develop approaches to eliminating poverty and to strengthen ethical values in politics.

Aylwin received honorary degrees from universities in Australia, Canada, Colombia, France, Italy, Japan, Portugal, Spain, and the United States, as well as seven Chilean universities. In 1997, the Council of Europe awarded the North-South Prize to Aylwin and Mary Robinson, former president of Ireland, for their contributions to fostering human rights, democracy, and cooperation between Europe and Latin America.[19]

In 1998, he received the J. William Fulbright Prize for International Understanding.

Death

.jpg)

On 18 December 2015, Aylwin was hospitalized in Santiago after suffering a cranial injury in a fall at home.[20] He died on 19 April 2016, aged 97.[1]

His state funeral was held on 22 April 2016.[21]

Honours

Foreign

- Fulbright Association: William Fulbright Prize for International Understanding (1988)

References

- 1 2 Kandell, Jonathan; Bonnefoy, Pascale (2016-04-19). "Patricio Aylwin, President Who Guided Chile to Democracy, Dies at 97". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ↑ "Reseña Biográfica Parlamentaria – Patricio Aylwin Azócar". Historia Política Legislativa del Congreso Nacional de Chile. 20 May 2009.

- ↑ http://www.emol.com/noticias/Nacional/2018/08/20/917567/A-los-93-anos-fallece-el-ex-diputado-DC-y-defensor-de-los-DDHH-Andres-Aylwin.html

- ↑ "Paz Bascuñán y su primer hijo: "Tenía mucha ilusión de verlo y conocerlo"". La Tercera. 13 August 2009. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ↑ Harris M. Lentz (2014). Heads of States and Governments Since 1945. Routledge. ISBN 9781134264902.

- ↑ William F. Sater, "Patricio Aylwin Azócar" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 1, p. 249. Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ↑ "Man in the News: Patricio Aylwin; A Moderate Leads Chile". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ Sater, "Patricio Aylwin" p. 249.

- ↑ "Patricio Aylwin, Chile's first post-Pinochet president, dies". BBC. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ Linz, Juan J. & Stepan, Alfred. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

- ↑ Sater, "Patricio Aylwin", p. 249.

- ↑ Constructing democratic governance: South America in the 1990s by Jorge I. Domínguez and Abraham F. Lowenthal

- 1 2 A History of Chile, 1808–1994, by Simon Collier and William F. Sater

- ↑ Victims of the Chilean Miracle: Workers and Neoliberalism in the Pinochet Era, 1973–2002, edited by Peter Winn

- ↑ Safety nets, politics, and the poor: transitions to market economies by Carol Graham

- ↑ Fast forward: Latin America on the edge of the 21st century by Scott B. MacDonald and Georges A. Fauriol

- ↑ Development Challenges in the 1990s: Leading Policymakers Speak from Experience by Timothy Besley and Roberto Zagha

- ↑ Nash, Nathaniel C. (4 April 1993). "Chile Advances in a War on Poverty, And One Million Mouths Say 'Amen'". The New York Times.

- ↑ "The North South Prize of Lisbon". North-South Centre. Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 2008-02-15. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ↑ http://thepeninsulaqatar.com/news/international/362655/chilean-ex-president-aylwin-hospitalized-after-fall

- ↑ http://www.t13.cl/galeria/politica/fotos-funeral-estado-patricio-aylwin-cementerio-general

- ↑ "Senarai Penuh Penerima Darjah Kebesaran, Bintang dan Pingat Persekutuan Tahun 1991" (PDF).

- ↑ "24846 Real Decreto 1223/1990" (PDF). 12 October 1990. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ "10428 Real Decreto 433/1991". 6 April 1991. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Patricio Aylwin. |

- Official Biography in section Galería de Presidentes (President's Gallery) (in Spanish)

- Biography by CIDOB (in Spanish)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Tomás Pablo |

President of the Senate of Chile 1971–1972 |

Succeeded by José Ignacio Palma |

| Preceded by Augusto Pinochet |

President of Chile 1990–1994 |

Succeeded by Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Tomás Reyes |

Falange Nacional President 1951–1952 |

Succeeded by Tomás Reyes |

| Preceded by Narciso Irureta |

Christian Democrat Party President 1973–1976 |

Succeeded by Andrés Zaldívar |

| Preceded by Gabriel Valdés |

Christian Democrat Party President 1989–1991 |

Succeeded by Andrés Zaldívar |