Patagium

The patagium (plural: patagia) is a membranous structure that assists an animal in gliding or flight. The structure is found in living and extinct groups of animals including bats, birds, some dromaeosaurs, pterosaurs, gliding mammals, some flying lizards, and flying frogs.

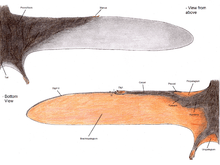

Bats

In bats, the skin forming the surface of the wing is an extension of the skin of the abdomen that runs to the tip of each digit, uniting the forelimb with the body.

The patagium of a bat has four distinct parts:

- Propatagium: the patagium present from the neck to the first digit.

- Dactylopatagium: the portion found within the digits.

- Plagiopatagium: the portion found between the last digit and the hindlimbs.

- Uropatagium: the posterior portion of the body between the two hindlimbs.

Pterosaurs

In the flying pterosaurs, the patagium is also composed of the skin forming the surface of the wing. In these ornithodirans, the skin was extended to the tip of the elongated fourth finger of each hand.

The patagium of a pterosaur had three distinct parts:

- Propatagium: the patagium present from the shoulder to the wrist. Pterosaurs developed a unique bone to support this membrane, the pteroid.

- Brachiopatagium: the portion stretching from the fourth finger to the hindlimbs.

- Uropatagium or cruropatagium: the anterior portion between the two hindlimbs, depending on whether it did or did not include the tail respectively.

- Podopatagium: a hypothetical portion stretching in between the legs that includes the tail, but the tail does not reach to the edge.

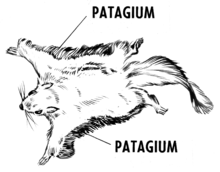

Gliding mammals

Flying squirrels, sugar gliders, colugos, anomalures and other mammals also have patagia that extends between the limbs; as in bats and pterosaurs, they also possess propatagia and uropatagia. Though the forelimb is not as specialised as in true flyers, the membrane tends to be an equally complex organ, composed of various muscle groups and fibers.[1][2] Various species have styliform bones to support the membranes, either on the elbow (colugos, anomalures, greater glider, Eomys) or on the wrist (flying squirrels).

Other

In gliding species, such as some lizards and flying frogs, it is the flat parachute-like extension of skin that catches the air, which allows gliding flight.

In some lepidoptera insect species, it is one of a pair of small sensory organs situated at the bases of the anterior wings.

In birds, the propatagium is the elastic fold of skin extending from the shoulder to the carpal joint, making up the leading edge of the inner wing. Many authors use the term to describe the fold of skin between the body (behind the shoulder) and the elbow that houses the outer segments of the latissimus dorsi caudalis and triceps scapularis muscles.[3] Similarly the fleshy pad that houses the follicles of the remiges (primary and secondary feathers) caudal to the hand and the ulna is also often referred to as a patagium.[4] The interremigial ligament that connects the bases all the primary and secondary feathers as it passes from the tip of the hand to the elbow is thought to represent the caudal edge of the ancestral form of this patagium.

Yi qi has a rather elaborate, superficially bat-like patagium in the forelimbs, unique among dinosaurs. The exact extent isn't clear, but it was extensive and supported by a long styliform bone as in gliding mammals. Other scansoriopterygids might have had similar patagia, based on their long third fingers.

A patagium has been found in the dinosaur Psittacosaurus, and ran from the animal's ankle to the base of the tail.[5]

References

- ↑ Functional anatomy of gliding membrane muscles in the sugar glider (Petaurus breviceps).

- ↑ Evolutionary transformation of the cervicobrachial plexus in the colugo (Cynocephalidae: Dermoptera) with a comparison to treeshrews (Tupaiidae: Scandentia) and strepsirrhines (Strepsirrhini: Primates). Folia Morphol (Warsz). 2012 Nov;71(4):228-39.

- ↑ Pennycuick, C.J. (2008). Modelling the flying bird. Amsterdam: Academic Press. ISBN 9780123742995.

- ↑ King, Antony S. (1985). Raikow RJ Locomotor system. Form and function in birds Vol3. London [u.a.]: Acad. Press. ISBN 9780124075030.

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/sep/14/scientists-reveal-most-accurate-depiction-of-a-dinosaur-ever-created