Barngarla people

The Barngarla, formerly known as Parnkalla, are an Aboriginal people of the Port Lincoln, Whyalla and Port Augusta areas. The Barngarla are the traditional owners of much of Eyre Peninsula, South Australia, Australia.[1][2]

Language

Barngarla died out in the 1960s.[3]

Israeli linguist Professor Ghil'ad Zuckermann contacted the Barngarla community in 2011 proposing to revive it, the project of reclamation being accepted enthusiastically by people of Barngarla descent. Workshops to this end were started in Port Lincoln, Whyalla and Port Augusta in 2012.[4] The reclamation is based on 170-year-old documents.[5]

Country

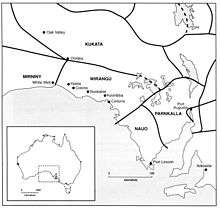

In Tindale's estimation, they Barngarla's traditional lands covered some 17,500 square miles (45,000 km2), around the eastern side of Lake Torrens south of Edeowie and west of Hookina and Port Augusta. The western reaches extended as far as Island Lagoon and Yardea. Woorakimba, Hesso, Yudnapinna, and the Gawler Ranges are formed part of Barngarla lands. The southern frontier lay around Kimba, Darke Peak, Cleve, and Franklin Harbour.[6]

Social organisation

The Barngarla had two tribal divisions, respectively, the northern Wartabanggala, who ranged from north of Port Augusta to Ogden Hill and the vicinity of Quorn and Beltana. A southern branch, the Malkaripangala, lived down the western side of the Spencer Gulf.[6]

In 1844 the missionary C. W. Schürmann stated that the Barngarla were divided into two classes, the Mattiri and Karraru.[7] This was criticized by the ethnographer R. H. Mathews, who, surveying South Australian tribes, argued that Schürmann had mixed them up, and that the proper divisions, which he called phratries shared by all these tribes was as follows:[8]

| Phratry | Husband | Wife | Offspring |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Kirrarroo | Matturri | Matturri |

| B | Matturri | Kirraroo | Kirraroo |

The Barngarla practiced both circumcision and subincision.[6]

Culture

A practice known as 'singing to the sharks' was an important ritual in Barngarla culture, a technique which expired when its last traditional practitioner died in the 1960s. The performance consisted of men lining the cliffs of bays in the Eyre peninsula and singing out, while their chants were accompanied by women dancing on the beach. The aim was to enlist sharks and dolphins in driving shoals of fish towards the shore where fishers in the shallows could make their catch.[3]

History of contact

Even before white colonization, the Barngarla were under pressure from the Kokatha, who were on the move southwards, forcing the Barngarla to retreat from their traditional northern boundaries. One effect was to cut off their access to certain woods used in spear-making, so that they finally had to forage as far as Tumby Bay in order to get supplies of whipstick mallee ash.[6]

Barngarla native title

On 22 January 2015 the Barngarla people were granted native title over much of Eyre Peninsula. They had applied for 44,500 square kilometres (11,000,000 acres) and received most of it.[lower-alpha 2][10]

Alternative names

- Banggala, Bahngala

- Pankalla, Parnkalla,Parn-kal-la,Pankarla

- Pamkala

- Punkalla

- Bangala, Bungela

- Punkirla

- Bungeha

- Kortabina. (toponym)[11]

- Willeuroo[12] ("west"/ "westerner")

- Arkaba-tura. (men of Arkaba, a toponym

- Jadliaura people

- Wanbirujurari. ("men of the seacoast". Northern tribal term for southern hordes)

- Willara

- Kooapudna. (Franklin Harbour horde)

- Kooapidna[6]

Some words

- wilga (tame dog).

- kurdninni (wild dog).

- pappi (father).

- ngammi (mother).

- koopa (whiteman).[13]

- gadalyili, goonya, walgara (shark).[lower-alpha 3]

Notes

- ↑ Tribal boundaries, after Tindale (1974), adapted from Hercus (1999).

- ↑ Judge Mansfield wrote:'The fact that Barngarla language is now being relearnt by some claimants, due to the work of Adelaide University academic Ghil'ad Zuckermann, is not evidence of continuity of the Barngarla language, although it is evidence of continuity of a notion of Barngarla identity, a notion that clearly existed amongst the Barngarla community at 1846, when Barngarla people told Schürmann of the "Barngarla matta", and which can thus be inferred to have existed at sovereignty.'[9]

- ↑ These three distinct terms for the one species are thought to have designated nuances whose differential meanings are no longer known.[3]

Citations

- ↑ Howitt 1904, p. ?.

- ↑ Prichard 1847, p. 79.

- 1 2 3 Goldsworthy 2014.

- ↑ Atkinson 2013.

- ↑ Anderson 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tindale 1974, p. 216.

- ↑ Mathews 1900, p. 79.

- ↑ Mathews 1900, p. 82.

- ↑ Mansfield 2015.

- ↑ Gage & Whiting 2015.

- ↑ Green 1886, p. 126.

- ↑ Bryant 1879, p. 103.

- ↑ Le Souef & Holden 1886, p. 8.

Sources

- "AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia". AIATSIS.

- Anderson, Lainie (6 May 2012). "Australia's unspeakable indigenous tragedy". The Punch.

- Angas, George French (1847). Savage life and scenes in Australia and New Zealand: being an artist's impressions of countries and people at the Antipodes (PDF). 1, 2. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Atkinson, Stephen (20 September 2013). "Language lost and regained". The Australian.

- Bryant, James (1879). "Gawler Ranges". In Taplin, George. Folklore, manners, customs and languages of the South Australian aborigines (PDF). Adelaide: E Spiller, Acting Government Printer. p. 103.

- Clendon, Mark (2015). Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla grammar: A commentary on the first section of A vocabulary of the Parnkalla language. University of Adelaide Press. ISBN 978-1-925-26111-0.

- Eylmann, Erhard (1908). Die Eingeborenen der Kolonie Südaustralien (PDF). Berlin: D.Reimer.

- Gage, Nicola; Whiting, Natalie (28 January 2015). "Barngarla people granted partial native title over large area of SA Eyre Peninsula,". ABC News.

- Goldsworthy, Anna (September 2014). "In Port Augusta, an Israeli linguist is helping the Barngarla people reclaim their language". The Monthly.

- Green, W. M. (1886). "Eastern Shore of Lake Torrens". In Curr, Edward Micklethwaite. The Australian race: its origin, languages, customs, place of landing in Australia and the routes by which it spread itself over the continent (PDF). Volume 2. Melbourne: J. Ferres. pp. 126–127.

- Howitt, Alfred William (1904). The native tribes of south-east Australia (PDF). Macmillan.

- Le Souef, A. A. C; Holden, R.W. (1886). "Port Lincoln" (PDF). In Curr, Edward Micklethwaite. The Australian race: its origin, languages, customs, place of landing in Australia and the routes by which it spread itself over the continent. Volume 2. Melbourne: J. Ferres. pp. 8–9.

- Mansfield, John (2015). "Croft on behalf of the Barngarla Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia". Federal Court of Australia.

- Mathews, R. H. (January 1900). "Divisions of the South Australian Aborigines". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 39 (161): 78–91+93. JSTOR 983545.

- Prichard, James Cowles (1847). Researches into the physical history of mankind (PDF). Volume 5 (3rd ed.). Sherwood, Gilbert & Piper.

- Schürmann, Clamor Wilhelm (1879). "The Aboriginal Tribes of Port Lincoln" (PDF). In Woods, James Dominick. The Native Tribes of South Australia. Adelaide: E.S. Wigg & Son. pp. 207–252.

- Strehlow, C. (1910). Leonhardi, Moritz von, ed. Die Aranda- und Loritja-Stämme in Zentral-Australien Part 3 (PDF). Joseph Baer & Co.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Pangkala(SA)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad; Walsh, Michael (2014). Heinrich, Patrick; Ostler, Nicholas, eds. "Our Ancestors Are Happy!": Revivalistics in the Service of Indigenous Wellbeing. FEL XVIII Ockinawa: Indigenous Languages: their Value to the Community. Foundation for Endangered Languages and Ryukyuan Heritage Language Society. pp. 113–119 – via professorzuckermann.com.