Pardon for Morant, Handcock and Witton

Pardon for Morant, Handcock and Witton refers to various attempts to secure a pardon for three Australian [1] soldiers convicted of war crimes - the murder of several Boer prisoners-of-war [2] - during the Second Boer War.

Following four courts martial in early 1902, Lieutenants Peter Joseph Handcock and Harry "Breaker" Morant, of the Bushveldt Carbineers (BVC) of the British Army, were executed by a firing squad of Cameron Highlanders, in Pretoria, South Africa, on 27 February 1902, 18 hours after they had been sentenced. Despite the court recommending mercy in both cases, Lord Kitchener confirmed their death sentences. Kitchener personally signed their death warrants.

Following the court also recommending mercy in his case, the sentence of a third brother officer, Lieutenant George Ramsdale Witton, was commuted to life imprisonment by Lord Kitchener. Following public pressure, Witton was released on 11 August 1904, but never pardoned.

As part of an extended historical process (dating from the time of the original courts martial in 1902), and seeking to redress alleged injustices towards all three men, and to gain formal recognition that the verdicts convicting the three for murder, were, in each case, "unsafe verdicts", an Australian military lawyer, Commander James William Unkles, of the Royal Australian Naval Reserve sent petitions for pardons for Morant, Handcock, and Witton to both Queen Elizabeth II and to the Petitions Committee of the Australian House of Representatives in October 2009. The British Government chose to not issue a pardon in November 2010 as there was no historical evidence to justify overturning the court martial decision. The Australian Government announced in May 2012 that it would not seek a pardon for Morant from the British Government as he and the other two men were guilty of killing the prisoners.

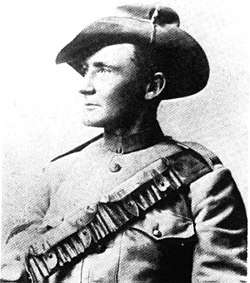

Major James Francis Thomas

.jpeg)

In their courts-martial, the accused Morant, Handcock, and Witton were all defended by James Francis Thomas (1861–1942),[3] a solicitor from Tenterfield, New South Wales.

He had studied law at Sydney University, served as an articled clerk in a reputable Sydney law practice,[4] and had been admitted (unconditionally) to practise as a solicitor on 28 May 1887.[5] However, he had never been admitted to practise as a barrister, and had no substantial court room experience of any kind.

Thomas had previously served with distinction, with the rank of Captain in the New South Wales Citizens' Bushmen Contingent. In 1902, he was unattached, and in South Africa, and solely due to his experience as a solicitor, was suddenly promoted to Major and coerced into representing the three accused; despite having no experience of any sort of the theory or practice of military law, or of the role of a barrister.[6]

Principle of condonation in British military law

The principle of condonation in British military law is traced back to the "Memorandum on Corporal Punishment" issued by the Duke of Wellington on 4 March 1832:

- "The performance of a duty of honour or of trust, after the knowledge of an offence committed by a soldier, ought to convey a pardon for the offence."[7]

According to Clode's Military Forces of the Crown (1869):

- "The principle of condonation for criminal offences is peculiar to the Military Code, and is of comparatively modern origin [viz., The Duke of Wellington's Memorandum]. Sir Walter Raleigh served the Crown under a special Commission, giving him Supreme Command, with the power of life and death over others, but he was afterwards executed upon his former conviction — the doctrine then laid down being "that the King might use the service of any of his subjects in what employment he pleased, and it should not be any dispensation for former offences". The rule is not so now, as applied to Military offences. "The performance of a duty of honour or of trust, after the knowledge of an offence committed, ought," said the late Duke of Wellington, "to convey a pardon for the offence"…[8]

Legal opinion (Isaac Isaacs, 1902)

.jpeg)

On 28 August 1902, the Member for Indi in the Federal Parliament, the eminent jurist Isaac Isaacs, published a legal opinion which recommended that George Witton petition the British monarch, King Edward VII, for a pardon.[9]

Witton petition (1904)

In 1904 a printed petition to King Edward VII was circulated in Australia, for signature by interested parties, requesting clemency in the form of (a) a pardon for George Witton, and (b) the immediate release of Witton from his incarceration. At least one copy of the petition, signed by thirty-seven individuals from the town of Colebrook, Tasmania, is extant. The petition, it seems, was never sent on to its final destination, and this was, most likely, because Witton had been released from custody (on 11 August 1904) before it could be sent.[10]

In 1907 the publication in Australia of Witton's book Scapegoats of the Empire revived debate about the convictions.

.jpeg)

Unkles' petitions (October 2009)

In October 2009, the Australian military lawyer, Commander James William Unkles, of the Royal Australian Naval Reserve sent petitions for pardons for Morant, Handcock, and Witton to both Queen Elizabeth II and to the Petitions Committee of the Australian House of Representatives in October 2009.

The first petition was considered by the British Government, on behalf of the Queen—"The petition argued that the convictions were unsafe and that their trial was unfair because the men were denied the right to communicate with the Australian government, refused an opportunity to prepare their cases and blocked from lodging an appeal."[11]—and, in November 2010, the UK Ministry of Defence issued a statement that the appeal had been rejected:

"After detailed historical and legal consideration, the Secretary of State has concluded that no new primary evidence has come to light which supports the petition to overturn the original courts-martial verdicts and sentences". (UK Ministry of Defence).[11]

The second petition was considered by the House of Representatives' Petitions Committee at a public hearing on Monday, 15 March 2010. Unkles appeared before the committee, along with others, including the historian Craig Wilcox. On Monday, 27 February 2012, in a speech delivered to the House of Representatives on the 110-year anniversary of the sentencing of the three men, Alex Hawke, M.P. described the case for the pardons as "strong and compelling".[12]

Roxon's rejection (May 2012)

In May 2012, Attorney General Nicola Roxon informed Unkles that the Australian Government would not seek a pardon for Morant from the British Government, on the grounds that Morant, Handcock and Witton did, in fact, kill unarmed Boer prisoners and others.[13] Roxon's letter to Unkles stated that in Australia "a pardon for a Commonwealth offence would generally only be granted where the offender is both morally and technically innocent of the offence".[14] Moreover, her letter stated that "Despite the time that has passed ... I consider seeking a pardon ... could be rightly perceived as glossing over very grave criminal acts".[15]

Following Roxon's decision, Robert McClelland, who served as Australia's Attorney-General, from 3 December 2007 to 14 December 2011 (immediately preceding Roxon), said that he had "concerns over a failure of procedural fairness for Morant and his two co-accused", and announced that "he had decided on principle to write to the British government in his capacity as a private citizen who was a member of parliament".[16]

High Court application (2013)

In July 2013, Unkles said he was planning to file documentation to the High Court in August seeking "a review of the British government decision not to help an independent inquiry".[17]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Note: Morant and the other accused were actually British citizens at the time, and were serving in the British Army.

- ↑ Note; technically no such legal status existed at the time relevant as there had been no declaration of war, nor were the Boers recognised as representing any formal government. Legally the deceased were civilians.

- ↑ Anonymous (2015-06-23). "Cemeteries". www.tenterfield.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 2017-04-21.

- ↑ Public Notices: James Francis Thomas, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Thursday, 26 May 1887), p.2; Public Notices: James Francis Thomas, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Friday, 27 May 1887), p.2;

- ↑ Supreme Court Proceedings: Admission of Attorneys, Australian Town and Country Journal, (Saturday, 4 June 1887), p.14; Law Report: Supreme Court: Saturday, 28 May: Admission of Attorneys, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Monday, 30 May 1887), p.4.

- ↑ Note: it was not usual for a defendant to have any legally-qualified person representing him in his defence during a court martial in-the-field. Normally such qualified persons were simply not available.

- ↑ Memorandum on Corporal Punishment (4 March 1832), pp.233–239, passage cited is at p.237.

- ↑ Clode, C.M., The Military Forces of the Crown: Their Administration and Government, in Two Volumes: Volume I, John Murray, (London), 1869, p.173 (84. Condonation of Military Offences)

- ↑ Isaacs, (1902).

- ↑ 1904 Witton Petition.

- 1 2 Malkin 2010.

- ↑ House of Representatives: Constituency Statement: Alex Hawke: Speech: Lieutenants Morant, Handcock and Witton (Monday, 27 February 2012).

- ↑ Welch, 2012.

- ↑ Griffiths, Meredith (10 May 2012). "Roxon rejects Morant pardon plea". ABC News. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ↑ Nicholson, Brendan (10 May 2012). "Pardon ruled out for Harry 'Breaker' Morant". The Australian. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ↑ Berkovic, 2012, p.3.

- ↑ Copping, Jasper (25 July 2013). "High Court 'pardon' bid for Boer war soldier 'Breaker' Morant". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

References

- Anon, "Execution of Officers: Important Statement by Mr. Barton", Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal, (Thursday, 3 April 1902), p.2.

- Anon, "Despatch from Lord Kitchener: Morant, Handcock, and Witton: Charged with Twenty Murders", Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal, (Monday, 7 April 1902), p.3.

- 'Our London Correspondent', "The Executed Officers: Statement by the War Office", Australian Town and Country Journal, (Saturday, 12 April 1902), p.13.

- Executed Officers: Detailed Reports of the Trial: Five Main Charges, The Brisbane Courier, (Saturday, 24 May 1902), p.6.

- Isaacs, I.A., "Opinion of the Hon. Isaac A. Isaacs K.C., M.P., re the case of Lieutenant Witton", (Melbourne), 28 August 1902.

- 'L.', "Australian Military Legislation", The Sydney Morning Herald, (Wednesday, 1 July 1903), p.5.

- Petition for clemency, pardon, and the immediate release from incarceration of George Ramsdale Witton, addressed to King Edward VII, and signed by 37 citizens of Colebrook, Tasmania, c.1904.

- Witton, G.R., Scapegoats of the Empire, Angus & Robertson, (Sydney), 1907.

- Copeland, H., "A Tragic memory of the Boer War: When Two Australian Officers Were Shot by Lord Kitchener's Orders", The Argus Week-End Magazine, (Saturday, 11 June 1938), p.6.

- Paterson, A.B. ("Banjo"), "An Execution and a Royal Pardon", The Sydney Morning Herald, (Saturday, 25 February 1939), p.21.

- Burke, A., "Melodrama of Boer War", The Sydney Morning Herald, (Saturday, 7 August 1954), p.14.

- "Bartle Frere", "Harry Morant", The Townsville Daily Bulletin, (Friday, 10 December 1954), p.9.

- "Move to Bring Morant Home", The Canberra Times, (Friday, 26 September 1980), p.3.

- Standing Committee on Petitions, "Petition regarding the convictions of Morant, Handcock and Witton", House of Representatives, (Canberra), 15 March 2010.

- Malkin, B., "Britain rejects pardon for executed solider {sic} Breaker Morant", The Telegraph, 29 August, 2013.

- Wald, T., "Royal pardon for Harry ‘Breaker' Morant rejected by British Government", Herald Sun, 12 November 2010.

- Unkles, J., "Justice has been denied the Breaker for too long", The Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday, 17 December 2010.

- Welch, D., "Roxon Rejects Pardon Bid for Breaker Morant", Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday, 10 May 2012.

- Jean, D., "Fight to Go on to Pardon for Breaker", The Adelaide Advertiser, (Friday, 11 May 2012), p.39.

- Berkovic, N., "McClelland defies A-G on Morant", The Australian, (Friday, 11 May 2012), p. 3.

External links

- House of Representatives' Grievance Debate: Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant, (speaker Alex Hawle, MP), Monday, 15 March 2010.

- Standing Committee on Petitions, "Petition regarding the convictions of Morant, Handcock and Witton", House of Representatives, (Canberra), 15 March 2010.

- National Boer War Memorial Association: Petition for a Pardon for Lieutenants Morant, Handcock and Witton.

- Australians at War: Boer War: Major Thomas Defended Breaker Morant.

- Personal Histories: Boer War & WW1: James Francis Thomas - The Man Who Defended Breaker Morant.