Pangolin trade

The pangolin trade is the illegal poaching, trafficking, and sale of pangolins, parts of pangolins, or pangolin-derived products. Pangolins are believed to be the world's most trafficked mammal, other than humans, accounting for as much as 20% of all illegal wildlife trade.[1][2][3] According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), more than a million pangolins were poached in the decade prior to 2014.[4]

The animals are trafficked mainly for their scales, which are believed to treat a variety of health conditions in traditional Chinese medicine, and as a luxury food in Vietnam and China.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which regulates the international wildlife trade, has placed restrictions on the pangolin market since 1975, and in 2016, it added all eight pangolin species to its Appendix I, reserved for the strictest prohibitions on animals threatened with extinction.[5][6] They are also listed on the IUCN Red List, all with decreasing populations and designations ranging from Vulnerable to Critically Endangered.[7]

Background

.jpg)

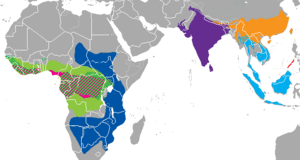

Pangolins are mammals of the order Pholidota, of which there is one extant family, Manidae, with three genera: Manis includes four species in Asia, and Phataginus and Smutsia each comprise two species in Africa. They are the only mammal known to have a layer of large, protective keratin scales covering their skin. Though sometimes known by the common name "scaly anteater," and formerly considered to be in the same order as anteaters, they are taxonomically distant, grouped with Carnivora under the clade Ferae.

Pangolin behavior varies by species, with some living on the ground, in underground burrows, and some living in trees. A common predator, big cats, struggle to contend with pangolins' scales when rolled up. But while well-equipped to defend against natural predators, they are easily caught by poachers, who simply pick up the animals when they roll into a ball.[2][5]

All eight species of pangolin are listed on the IUCN Red List, with designations ranging from Vulnerable to Critically Endangered.[7] According to the IUCN and other scientists and activists, the populations of all species are rapidly decreasing.[7][1]

History

The pangolin trade is centuries old. An early known example is in 1820, when Francis Rawdon, 1st Marquis of Hastinges and East India Company Governor General in Bengal, presented King George III with a coat and helmet made with the scales of Manis crassicaudata.[8] The gifts are now stored in the Royal Armouries in Leeds.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which regulates the international wildlife trade, added the eight known species of pangolin to its appendices in 1975. CITES places species it seeks to protect in three appendices organized according to urgency and, correspondingly, the strictness of the regulations. Appendix I includes the strictest prohibitions and is reserved for animals threatened with extinction.[6] In 1975, Smutsia temminckii was placed in Appendix I; Manis crassicaudata, Manis culionensis, Manis javanica, and Manis pentadactyla were placed in Appendix II; Smutsia gigantea, Phataginus tetradactyla, and Phataginus tricuspis were placed in Appendix III.[9] In 1995, Smutsia and Phataginus were moved to Appendix II. Finally, in 2016, at the 17th CITES Conference of Parties in Johannesburg, representatives of 182 countries unanimously enacted a ban on the international trade of all pangolin species by moving them to Appendix I.[5] Though the individual species are listed in Appendix I, the family as a whole (Manidae) is under Appendix II, with the implication that if additional species are discovered, they will be automatically placed in Appendix II.[9]

Despite restrictions on trade in place since 1975, enforcement is not uniformly strong. Most efforts have focused on curbing the supply side of the trade, but demand remains high and there is a thriving black market. Pangolins are believed to be the world's most trafficked mammal, accounting for as much as 20% of all illegal wildlife trade.[1][2][3] In 2014, the Worldwatch Institute reported that more pangolins were seized than any other animal in Asia's wildlife black market.[10][11] Estimates place the number of pangolins poached each year at between 10,000 and 100,000.[2][1] The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) estimates that more than a million pangolins were poached in the decade prior to 2014.[4] Most are sent to China and Vietnam, where their meat is prized and scales used for medicinal purposes.[2]

African and Asian nations frequently report on noteworthy confiscations of pangolins and pangolin parts. When a Chinese boat ran into a coral reef in the Philippines in 2013, officials discovered it to be carrying 10 tonnes of frozen pangolins.[12]

Black market

.jpg)

The black market pangolin trade is primarily active in Asia. Demand is particularly high for their scales, but whole animals are also sold either living or dead for the production of other products with purported medicinal properties or for consumption as exotic food.

Scales

_(32575640450).jpg)

Pangolins have a thick layer of protective scales made from keratin, the same material that makes up human fingernails and rhinoceros horns.[8] Scales account for about 20% of the animal's weight. When threatened, pangolins curl into a ball, using the scales as armor to defend against predators.

In traditional Chinese medicine, the scales are used for a variety of purposes. The pangolins are boiled to remove the scales,[1] which are then dried and roasted, then sold based on claims that they can stimulate lactation,[2] help to drain pus,[2] and relieve skin diseases[8] or palsy.[2] As of 2015, pangolin scales were covered under some health insurance plans in Vietnam.[13]

The scales can cost more than $3,000/kg on the black market.[2]

Meat

Pangolin meat is prized as a delicacy in parts of China and Vietnam.[3] In China, the meat is believed to have nutritional value that makes it particularly good for kidney function.[8]

In Vietnam, restaurants can charge as much as $150 per pound of pangolin meat.[8] At one restaurant in Ho Chi Minh City, pangolin is the most expensive item on its menu of exotic wildlife, requiring a deposit and a few hours' notice. Restaurant employees kill the animal at the table, in front of diners, to show authenticity and freshness.[13]

According to Dan Challender of the International Union for Conservation of Nature's pangolin specialist group, "The fact that it's illegal isn't played down and is even attractive, because it adds this element that you live beyond the law."[13]

Other products

Though meat and scales are the primary drivers of the pangolin trade, there are also other less common parts and uses. Pangolin wine is produced by boiling rice wine with a baby pangolin.[1] It is purported to have various healing properties, such as for treatment of skin disease and improved breathing.[1][14] Pangolin blood is similarly viewed by some as having medicinal value.[1] Pangolin skins have also been trafficked. In 2015, Uganda reported it had seized two tons of pangolin skins.[8]

Conservation and enforcement

_(32575641040).jpg)

Governments and non-governmental organizations have undertaken a variety of conservation efforts, with varying activities and degrees of success in different parts of the world. The IUCN's Species Survival Commission formed a Pangolin Specialist Group in 2012, comprising 100 experts from 25 countries, hosted by the Zoological Society of London.[4] It also coordinated an annual awareness day, World Pangolin Day, on February 15, starting in 2014.[1]

Public awareness and support for conservation efforts can be important to their success. According to Annette Olsson, technical advisor at Conservation International, one of the problems the pangolin faces is that, unlike more well-known endangered animals like elephants, rhinoceroses, pandas, or tigers, "It's not huge and not very charismatic. It's small and weird and just disappearing."[8] Legal measures focus on curbing poaching and the supply side of the market, while media attention and public awareness can be crucial to the success to animal conservation efforts by affecting demand. According to CNN's John D. Sutter, "the pangolin needs international celebrity to survive, and the CITES vote is a critical step toward achieving that celebrity."[14] In some part due to lack of attention, pangolin conservation has not been a significant recipient of funding from governments or NGOs.[1]

On 17 February 2017, a day before World Pangolin Day, officials in Cameroon burned 3 tonnes of confiscated pangolin scales, representing up to 10,000 animals. The Cameroonian government had confiscated more than 8 tonnes of pangolin scales since 2013.[15] This conservation strategy is similar to the increasingly common destroying confiscated ivory to deter poaching and generate public outrage or action. As with ivory, there is an opportunity cost to destroying the material, trading awareness via public spectacle for the money which could be gained by reselling what was confiscated.[1]

In Vietnam, one of the countries in which the pangolin trade is most active, activists have access to only two centers able to take care of pangolins, and together they can only keep 50 animals in total.[13] CNN characterized Vietnamese activists as having "vastly inadequate support."[1]

A significant challenge to conservationists is the difficulty pangolins have in captivity. The animals do not adapt well to alternative or artificial foods and suffer stress, depression and malnutrition, leading to significantly shortened lifespans.[2][8] For these reasons they are rarely found in zoos or visible to the public while alive.[1] For example, as of 2015, the only zoo in the United States to have a pangolin is the San Diego Zoo, and only one because the other died due to digestive problems.[1] Part of the problem, which is also a major cause of the problem, is that without the ability to observe healthy pangolins in captivity, there is still a lot about pangolins humans have not yet been able to learn — variety in their diet, maximum lifespan, maximum size, mating habits, and many aspects of their behavior.[1]

In an episode of the BBC program Natural World, David Attenborough highlighted the Sunda pangolin as one of the 10 species he would like to save from extinction, recalling rescuing "one of the most endearing animals I have ever met" from being eaten while working on a film early in his career.[16]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sutter, John D. (April 2014). "Change the List: The Most Trafficked Mammal You've Never Heard Of". CNN.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Kelly, Guy (1 January 2015). "Pangolins: 13 facts about the world's most hunted animal". The Telegraph.

- 1 2 3 Franchineau, Helene (5 October 2016). "A ranger, poacher and investigator explain pangolin trade". Associated Press.

- 1 2 3 "Eating pangolins to extinction". IUCN. 29 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 Carrington, Damian (28 September 2016). "Pangolins thrown a lifeline at global wildlife summit with total trade ban". The Guardian.

- 1 2 "How CITES works". CITES Secretariat, United Nations Environment Program. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- 1 2 3

"Manis crassicaudata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016-3. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

"Manis culionensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016-3. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

"Manis javanica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016-3. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

"Manis pentadactyla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016-3. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

"Phataginus tetradactyla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016-3. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

"Phataginus tricuspis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016-3. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

"Smutsia gigantea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016-3. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

"Smutsia temminckii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016-3. Retrieved 20 February 2017. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Goode, Erica (30 March 2015). "A Struggle to Save the Scaly Pangolin". New York Times.

- 1 2 "Checklist of CITES Species". CITES Secretariat, United Nations Environment Program. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ↑ Guilford, Gwynn (27 January 2014). "Demand for traditional Chinese medicine is killing off the world's quirkiest animal". Quartz.

- ↑ Block, Ben. "Illegal Pangolin Trade Threatens Rare Species". Worldwatch Institute. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ↑ Carrington, Damian (2013-04-15). "Chinese vessel on Philippine coral reef caught with illegal pangolin meat". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- 1 2 3 4 Nuwer, Rachel (30 March 2015). "In Vietnam, Rampant Wildlife Smuggling Prompts Little Concern". New York Times.

- 1 2 Sutter, John D. (28 September 2016). "This is the week to save the world's most trafficked mammal". CNN.

- ↑ "Cameroon Burns 3 Tons of Pangolin Scales". African Wildlife Foundation. 17 February 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ↑ Gray, Richard (28 October 2012). "Sir David Attenborough picks 10 animals he would take on his ark". The Telegraph.