Pan Am Flight 6

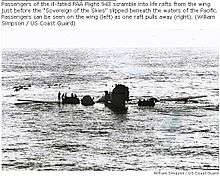

Pan Am Flight 6 ditching in the Pacific Ocean, photographed from US Coast Guard Cutter Pontchartrain | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | October 16, 1956 |

| Summary | Engine failure, ditching at sea |

| Site |

Pacific Ocean Northeast of Hawaii 30°01.5′N 140°09′W / 30.0250°N 140.150°WCoordinates: 30°01.5′N 140°09′W / 30.0250°N 140.150°W |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 377 Stratocruiser 10-29 |

| Aircraft name | Clipper Sovereign Of The Skies |

| Operator | Pan American World Airways |

| Registration | N90943 |

| Passengers | 24 |

| Crew | 7 |

| Fatalities | 0 |

| Survivors | 31 (all) |

Pan Am Flight 6 (registration N90943, and sometimes erroneously called Flight 943) was an around-the-world airline flight that ditched in the Pacific Ocean on October 16, 1956, after two of its four engines failed. Flight 6 left Philadelphia as a DC-6B and flew eastward to Europe and Asia on a planned multi-stop trip. On the evening of October 15, 1956, the flight left Honolulu on a Boeing 377 Stratocruiser Clipper named Sovereign Of The Skies (Pan Am fleet number 943, registered N90943). The accident was the basis for the 1958 film Crash Landing.

Accident details

The aircraft took off from Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, at 8:26 p.m. HST on the flight's last leg to San Francisco. After passing the point of equal time, the flight received permission to climb to an altitude of 21,000 ft (6,400 m). When that altitude was reached, at about 1:20 a.m., the No. 1 engine began to overspeed as power was reduced. The first officer, George Haaker, who was flying the plane, immediately slowed the plane by further reducing power and by extending the flaps, and an attempt was made to feather the propeller. The propeller would not feather and the engine continued to turn at excessive RPM. Captain Richard Ogg decided to cut off the oil supply to the engine. Eventually, the RPM declined and the engine seized. The propeller continued to windmill in the air stream, causing excessive drag that increased the fuel consumption. As a result, the plane was forced to fly much more slowly, below 150 knots (280 km/h), and lost altitude at the rate of 1,000 feet per minute (5.1 m/s). Climb power was set on the remaining three engines to slow the rate of descent. The No. 4 engine subsequently began to fail [1] and soon was producing only partial power at full throttle. At 2:45 a.m. the No. 4 engine began to backfire, forcing the crew to shut it down and feather the propeller.[2]

The crew calculated the added drag left them with insufficient fuel to reach San Francisco or to return to Honolulu. Captain Ogg radioed a message: "PanAm 90943, Flight 6, declaring an emergency over the Pacific".[3] In the 1950s the United States Coast Guard maintained a cutter at Ocean Station November between Hawaii and the California coast. This ship was able to provide weather information and passed on radio messages to aircraft in the vicinity. It was located at the "point of no return" and intended to provide assistance to aircraft in distress. On that night, the ship was the 255-foot USCGC Pontchartrain. Captain Ogg's message was relayed to the Pontchartrain[3] and the plane flew to the cutter's location, leveled off at 2,000 feet (610 m), and flew above it in eight-mile circles on the two remaining engines until daylight.[4]

Captain Ogg had decided to wait for daylight, since it was important to keep the wings level with the ocean swells at the ditching impact. That would be easier to achieve in full sunlight, improving the odds that passengers could be rescued, but he became concerned that the ocean waves were beginning to rise. As the plane circled the Coast Guard cutter, it was able to climb from 2,000 to 5,000 feet (610 to 1,520 m). At that altitude several practice approaches were made to see that the plane would be controllable at low speed (the goal was to have the lowest speed possible, just before touching the water). Delaying the ditching also ensured that more fuel would be consumed, making the plane lighter so it would float longer and minimizing the risk of fire in the event of a crash landing.[1]

Aware of the Pan Am Flight 845/26 accident the year before, in which a Boeing 377's tail section had broken off during a water landing, the captain told the flight's purser to clear passengers from the back of the plane.[1] The crew removed loose objects from the cabin, and prepared the passengers for the landing. As on other flights in the era, small children were allowed on their parents' laps, without separate seats or seat belts.[5]

At 5:40 Captain Ogg notified Pontchartrain that he was preparing to ditch. The cutter laid out a foam path for a best ditch heading of 315 degrees, to aid the captain to judge his height above the water. After a dry run the plane touched down at 6:15, at 90 knots (170 km/h) with full flaps and landing gear retracted, in sight of the Pontchartrain at 30°01.5'N, 140°09'W.[2] On touching the water, the plane moved along the surface for a few hundred yards. One wing hit a swell, causing the plane to rotate nearly 180 degrees to port, damaging the nose section and breaking off the tail.[1] All 31 on board survived the ditching. Three life rafts were deployed by the crew and passengers who had previously been assigned to help. One raft failed to inflate properly, but rescue boats from the cutter were able promptly to transfer the passengers from that raft. All were rescued by the Coast Guard before the last pieces of wreckage sank at 6:35 a.m. Crew on the cutter filmed the landing and the rescue.[6] A ten-minute film was later produced, including the recording of the radio conversation between the pilot and the Coast Guard.[4]

The passengers were housed in the ship's officers' quarters and returned to San Francisco several days later.[5] There were a few minor injuries, including an 18-month-old girl who bumped her head during the impact and was knocked unconscious. Forty-four cases of live canaries in the cargo hold were lost when the plane sank.[5]

Some time later, the crew received awards for their work on the flight, having prevented any fatalities.[7] Pilot Richard Ogg was the first recipient of the Civilian Airmanship Awards presented by the Order of Daedalians. [8]

Probable cause

A subsequent investigation report summarized the incident in this manner: "An initial mechanical failure which precluded feathering the no. 1 propeller and a subsequent mechanical failure which resulted in a complete loss of power from the no. 4 engine, the effects of which necessitated a ditching."[2]

Flight crew

- Captain Richard N. Ogg, age 43

- First Officer George L. Haaker, age 40

- Navigator Richard L. Brown, age 31

- Flight Engineer Frank Garcia Jr., age 30

Books and periodicals

- Adams, Michael R. (2010). Ocean Station: Operations of the U.S. Coast Guard, 1940–1977. Eastport, Maine: Nor'easter Press. ISBN 978-0-9779200-1-3. [Describes the ditching of Sovereign of the Skies and the rescue of its passengers and crew by the crew of USCGC Pontchartrain.]

- Brean, Herbert (October 29, 1956). "Ordeal On Flight 943: The Last Five Hours". Life: 23–30.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "This is it. > Vintage Wings of Canada". www.VintageWings.ca. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident Boeing 377 Stratocruiser 10-29 N90943 San Francisco, CA, USA". Aviation-Safety.net. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- 1 2 "Pan Am Clipper Makes Pacific Landing - Metropolitan Airport News". MetroAirportNews.com. November 2, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- 1 2 Negroni, Christine (November 8, 2017). "1956 Version of Landing an Airplane on Water". Retrieved December 12, 2017 – via NYTimes.com.

- 1 2 3 Matthew B. Stannard (2009-01-23). "Danville pilot has historical predecessor". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ M Voitier (August 13, 2009). "PanAm Flight 6 Ditching — crash Fleet number 943 Registration N90943". Retrieved December 12, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ↑ NEGRONI, CHRISTINE (November 10, 2017). "53 years before Sully, there was the 'Miracle on the Pacific'". Traveller.com.au. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ↑ "Flightline, Summer 2005, page 8" (PDF). AlliedPilots.org. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

External links

- Accident Investigation Report File No. 1-0121 U.S. Department of Transportation Archived Report

- Aviation Safety Network Description of the accident

- CAB Accident Report - Civil Aeronautics Board

- "HEROES: The Ditching". TIME. Monday, October 29, 1956.

- United States Coast Guard Video "Ready on Ocean Station November"

- Stannard, Matthew B. "Danville Pilot Has Historical Predecessor". San Francisco Chronicle. Saturday, January 24, 2009.

- Crash Landing (1958) on IMDb