Pain empathy

Pain empathy is a specific subgroup of empathy that involves recognizing and understanding another person’s pain. Empathy is the mental ability that allows one person to understand another person’s mental and emotional state and how to effectively respond to that person. When a person receives cues that another person is in pain, neural pain circuits within the brain are activated. There are several cues that can communicate pain to another person: visualization of the injury causing event, the injury itself, behavioral efforts of the injured to avoid further harm, and displays of pain and distress such as facial expressions, crying, and screaming.[1] From an evolutionary perspective, pain empathy is beneficial for human group survival since it provides motivation for non-injured people to offer aid to the injured and to avoid injury themselves.

Initiating Pain Empathy

Resonance

Perceiving another person's affective state can cause automatic changes in brain activity in the viewer. This automatic change in brain activity is known as resonance and helps initiate an empathetic response. The inferior frontal gyrus and the inferior parietal lobule are two regions of the brain associated with empathy resonance.[2]

Self other discrimination

In order to have empathy for another person, one must understand the context of that person’s experience while maintaining a certain degree of separation from their own experience. The ability to differentiate the source of an affective stimuli as originating from the self or from other another is known as self-other discrimination. Self-other discrimination is associated with the extrastriate body area (EBA), posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS), temporoparietal junction (TPJ), ventral premotor cortex, and the posterior and inferior parietal cortex.[2]

Response to painful facial expressions

A painful facial expression is one way in which the experience of pain is communicated from one individual to another. One study aimed to measure test subject’s related brain activity and facial muscle activity when they watched video clips of a variety of facial expressions including neutral emotion, joy, fear, and pain. The study found that when a subject is shown a painful facial expression, their late positive potential (LPP) is increased during the time period of 600-1000ms after the initial exposure of the stimulus. This increase in LPP for painful facial expressions was higher than the increase caused by other emotional expressions. [3]

Pain processing areas of the brain (The Pain Matrix)

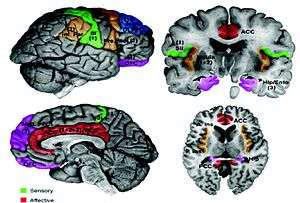

Several areas of the brain are related to the processing of pain and pain empathy.

One study used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure brain activity while during the experience of painful stimuli or while observing someone else received a painful stimuli. The study group consisted of 16 couples since it was likely these individuals would have empathy for one another. One person would receive a painful stimulus via electrode to the back of their hand while their partner observed and brain activity was measured in both participants. The results from the fMRI are detailed below.[4]

First hand experience of pain

The activated brain regions in the person experiencing the pain firsthand included: contralateral sensorimotor cortex, bilateral secondary sensorimotor cortex, contralateral posterior insula, bilateral mid and anterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex, right ventrolateral and mediodorsal thalamus, brainstem, and mid and right lateral cerebellum.[4] One study used fMRI to observe brain activity of an individual receiving unpredictable laser pain stimuli. This study showed that the primary and secondary sensorimotor cortex, posterior insula, and lateral thalamus are involved in processing aspects of nociceptive stimuli such as location and intensity.[5]

Observed pain in others

Several brain regions including the bilateral anterior insula (AI), rostral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), brainstem, and cerebellum were activated both in instances of first person painful experience and observed painful experience. The bilateral anterior insula (AI) and rostral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) are therefore hypothesized to take part in the emotional reaction evoked from witnessing another in pain. The somatosensory region of the brain was not shown by fMRI to be excited during pain observation, rather only when the pain was experienced firsthand.[4]

One study recorded the brain activity of subjects using electroencephalography whilst subjects were shown footage of needle penetrating a hand. There was a recorded increase in activity in the frontal, temporal and parietal areas of the brain when the individuals were exposed to the footage and observed pain in others. The gamma band oscillations, which reflects brain activity, increased to 50–70 Hz. The usual gamma band oscillations in the brain is around 40 Hz. The results of the study suggests high gamma band oscillations could help provide an understanding of the neural basis of empathy for pain.[6]

Debates

It is unclear as to how much the pain matrix is involved in pain empathy. Some studies have found that when all neural components of the pain matrix are observed together, they are more related to one's reaction to the presence of stimuli than pain in particular.[7] The ability to empathize with the pain of others seems to be correlated only to certain parts of the pain matrix rather than the matrix as a whole.[4] Some have argued that only the affective components of the pain matrix, the anterior insula and the anterior cingulate cortex, are activated when it comes to pain empathy.[8]

Detection Methods

Magnetoencephalography

fMRI studies were not able to detect activity in the somatosensory cortex during pain empathy. Neuromagnetic oscillatory activity was recorded from the primary somatosensory cortex in order to determine if it is involved in pain empathy. When the left medial nerve was stimulated, post-stimulus rebounds of 10 Hz of somatosensory oscillations were quantified. These baseline somatosensory oscillations were suppressed when the subject observed a painful stimulus to a stranger. These results show that the somatosensory cortex is involved in the pain empathy response even though the activity could not be detected using fMRI techniques.[9]

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)

Single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) has been used to stimulate the motor cortex of a person observing another person’s actions, and this has been shown to increase the corticospinal excitability of associated with their motor resonance. TMS studies have shown that frontal structures of the motor resonance system are used to process information about other people’s physical actions.[2]

Motor evoked potential (MEP)

Sensorimotor contagion is an automatic reduction in corticospinal excitability due observing another person experiencing pain. In a study by Avenanti on pain empathy in racial bias, it was shown that when a person sees a needle being poked into the hand of another person, there is a reduced motor evoked potential (MEP) in the muscle of the observer’s hand.[10]

Lack of pain empathy

Lack of empathy occurs in several conditions including autism, schizophrenia, sadistic personality disorder, psychopathy, and sociopathy. One recent view is that an improper ratio of cortical excitability to inhibition causes empathy defects. Brain stimulation is being investigated for its potential to alter motor resonance, pain empathy, self-other discrimination, and mentalizing as a way to treat empathy related disorders.[2]

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenic patients are impaired in several empathy domains. They are less able to identify emotions, take on different perspectives, perform low level facial mirroring and are less sensitive in terms of affective responsiveness.[11] These individuals are less responsive to their own pain and are less empathetic to that of others as well.[12] In schizophrenic patients, there has been observed neural and structural alterations in brain regions that are normally associated with the processing of empathy. For example, alterations have been observed in the temporo-parietal junction and the amygdala, which are both involved in empathy. This is part of the reason why schizophrenic individuals have difficulties in understanding and reacting to the pain of others, prohibiting their ability to empathize with pain.[13]

One study used EEG to observe the brain activity of individuals with schizophrenia when shown hands and feet in painful situations. The results of the experiments suggested the ability to separate 'self' from 'others', which is essential to empathizing with other people, is impaired in the schizophrenic sample.[13] Another study concluded that schizophrenic individuals tend to process ‘other’ related pain stimuli in a way that is usually more associated with how self relevant stimuli are processed and it is because of this these individuals are less able to differentiate between the ‘self’ and the ‘other’.[14]

Schizophrenic subjects who participated in studies have also had difficulty assessing and discriminating between different levels of pain. For example, in one study, those with schizophrenia were less likely to be able to discriminate between ‘strong’ and ‘moderate’ pain levels than control subjects who did not have schizophrenia.[11] Subjects with schizophrenia were also less able to rate pain intensities from looking at different facial expressions.[12] The way in which these individuals empathize with pain may be caused partially by the lack of sensitivity in terms of affective processing of pain and the severity of their increased suspiciousness seen in many schizophrenics.

Those with schizophrenia have shown to be more easily disturbed by the negative emotions, which includes pain, of others compared to healthy samples in studies conducted.[13] Schizophrenics tend to feel increased levels of personal distress when perceiving any sign of pain in other people.[15] This tightened self-oriented negative emotion of personal distress has been described as ‘hyper sensitivity’ to the pain of others.[14] This 'hyper sensitivity' has been suggested to overwhelm the individual and hence impair their ability to empathetically respond and relate to the pain of others on a personal level. The increased levels of personal distress may increase the individual's need to reduce their own discomfort, meaning they give less attention to and empathize less with the pain of others.[15]

[16] Sadistic personality disorder

Psychopathy is thought to be caused by normal processing of social and emotional cues, but abnormal use of these cues.[2] One study used fMRI to look at the brain activity of youth with aggressive conduct disorder and socially normal youth when they observed empathy eliciting stimuli. The results showed that the aggressive conduct disorder group had activation in the amygdala and ventral striatum, which lead the researcher to believe that these subjects may get a rewarding feeling from viewing pain in others.[17]

Autism

Austism spectrum disorders are characterized by an impairment in the processing of social and emotional affective cues.[2]

Juvenile psychopathy

Young individuals who have callous and unemotional traits (CU) exhibit an overall lack of empathy. It has been thought that if a person experiences pain empathy they will be less likely to hurt others, since people that experience pain empathy have distress when another person is hurt.

One study involved showing juvenile psychopaths video clips of strangers experiencing painful stimuli. The results of the study showed that the juvenile psychopaths had atypical processing of these pain empathy eliciting stimuli in comparison with the normal juvenile controls. The central late positive potential (LPP), a late cognitive evaluative component of pain, was decreased in subjects with low CU traits. Subjects with high CU traits had both a decrease in central LPP and in frontal N120, an early affective arousal component of pain. There were also differences in the pain thresholds between normal test subjects, subjects with low CU traits, and subjects with high CU traits. The subjects with CU traits had higher pain thresholds than the controls, which suggests they were less sensitive to noxious pain. The results of the study show the CU trait juvenile’s lack of pain empathy was due to a lack of arousal due to another person’s distress rather than a lack of understanding of the other’s emotional state.[18]

Bias and Variation

There is evidence that individual empathetic responses to the pain of others are biased based on one's racial identity, in-group/out-group status and position on a social hierarchy. Experiences of pain empathy also varies between people depending on differences in personality such as the level of threat sensitivity in an individual. If the individual is highly sensitive to threat, their empathetic reactions to others in pain tends to be more intense compared to those who are not as sensitive.[19]

In-group bias

An experiment used a minimal group paradigm to create two groups, the in-group and the outgroup to which they assigned 30 subjects.[20] 30 healthy right handed subjects participated in a fMRI experimental session in which they were shown 128 photographs where right hands and feet were in painful situations. The results of the study did not report any sign of an in-group or out-group favoritism, meaning subjects did not feel higher levels of empathy based on the groups they were in.

Racial bias

An experiment utilizing transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) was performed in order to determine if another person’s race affected pain empathy by measuring inhibition of corticospinal excitability. Caucasian and black participants watched video clips of a needle penetrating a muscle in the right hand of a stranger who either belonged to their racial group or the other racial group. TMS was used to stimulate the left motor cortex and motor-evoked potentials (MEPs) were measured in the observer’s first dorsal interosseus (FDI) muscle of the right hand. The results of the experiment showed that when the video clip showed a hand belonging to a person of the same racial group, the measured corticospinal excitability to the right hand of the observer was reduced. This inhibition effect was not present when a subject viewed a clip of a hand belonging to a stranger outside of their racial group. This corticospinal inhibition occurs in first hand experience of pain, and suggests that there is activation of the observer's sensorimotor system while witnessing painful stimuli.[10]

Social hierarchy bias

An experiment placed individuals in a social hierarchy based on their skills when completing a task. The subjects were then scanned with functional magnetic resonance imaging while watching those of an inferior and superior status experience painful or non-painful stimulation. The results of the study concluded relative positions in a social hierarchy affects empathetic responses to pain in that individuals are more likely to be more empathetic to the pain of those in an inferior status than to those in a more superior status.[21] This suggests there is bias depending on one's position on a social hierarchy when it comes to pain empathy.

Empathy gap

Humans tend to underestimate the intensity of physical pain other individuals go through, which affects their empathetic reactions to the pain of others.[19]

Physicians and pain empathy response

Physicians are frequently exposed to people experiencing pain due to injury or illness, or have to inflict pain during the course of treatment. Physicians have to regulate their emotional response to this stimuli in order to effectively help the patient and maintain their own personal well being. Pain empathy can motivate an individual to help someone who is in pain, but repeated exposure to individuals in pain with no ability to regulate emotional arousal can cause distress. One study sought to determine if physicians had an altered response to viewing painful stimuli. Physicians and control subjects watched video clips of a stranger being poked with a needle into the hands or feet. fMRI was used to measure the hemodynamic activity within the brain while viewing the painful stimuli. The fMRI revealed that brain areas involved in the pain matrix: somatosensory cortex, anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulated nucleus (dACC), and the periaqueductal gray (PAG) were activated in the control subject population when viewing the needle penetration videos. The physicians had activation of higher order executive functioning in the brain as shown by activation of the dorsolateral and medial prefrontal cortex, both involved in self-regulation, and activation of the precentral, superior parietal, and temporoparietal junction, involved with executive attention. The physicians did not have activation of the anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulated nucleus (dACC), or the periaqueductal gray (PAG). The study concluded that physicians adapt to the healthcare environment by down regulating their automatic empathetic response to patient’s pain.[22]

Pain synesthesia

Synesthesia occurs when sensory information in one cognitive pathway causes a sensation through another cognitive pathway. One form of synesthesia will cause a person to see certain colors when triggered by certain numbers, letters, or words. Pain synesthesia is a form of synesthesia that causes a person to experience pain when seeing pain empathetic eliciting stimuli. The most common group for reporting pain synesthesia are patients with phantom limb syndrome.[23]

Cultural Variation

There has been evidence from several studies that there is cultural variation in pain empathy. One experiment in which British participants and East Asian participants were shown a video of a needle puncturing a hand helped to demonstrate these cultural variations.[24] The results showed British subjects demonstrated more empathetic concern and higher levels of emotional experience to do with empathy compared to the East Asian participants.

References

- ↑ Jean Decety, W. I. (Ed.). (2009). The Social Neuroscience of Empathy: MIT Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hetu, S.; Taschereau-Dumouchel, V.; Jackson, P. L. (2012). "Stimulating the brain to study social interactions and empathy. [Article]". Brain Stimulation. 5 (2): 95–102. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2012.03.005.

- ↑ Reicherts, P.; Wieser, M. J.; Gerdes, A. B. M.; Likowski, K. U.; Weyers, P.; Muhlberger, A.; Pauli, P. (2012). "Electrocortical evidence for preferential processing of dynamic pain expressions compared to other emotional expressions. [Article]". Pain. 153 (9): 1959–1964. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2012.06.017.

- 1 2 3 4 Singer, T. S. B.; O'Doherty, J; Kaube, H; Dolan, RJ; Frith, CD. (2004). "Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain". Science. 303 (5661): 1157–1162. doi:10.1126/science.1093535.

- ↑ Bingel, U.; Quante, M.; Knab, R.; Bromm, B.; Weiller, C.; Buchel, C. (2003). "Single trial fMRI reveals significant contralateral bias in responses to laser pain within thalamus and somatosensory cortices. [Article]". NeuroImage. 18 (3): 740–748. doi:10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00033-2.

- ↑ Motoyama, Y., Ogata, K., Hoka S., & Tobimatsu, S. (2010). "P15-15 Neural substrates of empathy for pain: Simultaneous recording of high density EEG and conventional ECG". Clinical Neurophysiology. 121. doi:10.1016/s1388-2457(10)60798-5.

- ↑ Michael, J. & Fardo, F. (2014). "What (If Anything) Is Shared in Pain Empathy? A Critical Discussion of De Vignemont and Jacob's Theory of the Neural Substrate of Pain Empathy". Philosophy of Science. 81 (1): 154–160. doi:10.1086/674203.

- ↑ Bufalari, I., Aprile, T., Avenanti, A., Di Russo, F., & Aglioti, S. (2007). "Empathy for Pain and Touch in the Human Somatosensory Cortex". Cerebral Cortex. 17 (11): 2553–2561. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhl161.

- ↑ Cheng, Y., Yang, C. Y., Lin, C. P., Lee, P. L., & Decety, J. (2008). The perception of pain in others suppresses somatosensory oscillations: A magnetoencephalography study.

- 1 2 Avenanti, A.; Sirigu, A.; Aglioti, S. M. (2010). "Racial bias reduces empathic sensorimotor resonance with other-race pain". Current Biology. 20 (11): 1018–1022. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.071.

- 1 2 Martins, M. J., Moura, B. L., Martins, I. P., Figueira, M. L. & Prkachin, K. M. (2011). "Sensitivity to expressions of pain in schizophrenia patients". Psychiatry Research. 189: 180–184. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2011.03.007.

- 1 2 Wojakiewicz, A., Januel, D., Braha, S., Prkachin, K., Danziger, N. & Bouhassira, D. (2013). "Alteration of pain recognition in schizophrenia". European Journal of Pain. 17: 1385–1392. doi:10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00310.x.

- 1 2 3 Gonzalez-Liencres, C., Brown, E. C., Tas, C., Breidenstein, A. & Brüne, M. (2016). "Alterations in event-related potential responses to empathy for pain in schizophrenia". Psychiatry Research. 241: 14–21. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.091.

- 1 2 Horan, W., Jimenez, A., Lee, J., Wynn, J., Eisenberger, N., & Green, M. (2016). "Pain empathy in schizophrenia: An fMRI study". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 11 (5): 154–160. doi:10.1093/scan/nsw002.

- 1 2 Didehbani, N., Shad, M. U., Tamminga, C. A., Kandalaft, M. R., Allen, T. T., Chapman, S. B., & Krawczyk, D. C. (2012). "Insight and empathy in schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Research. 142 (1–3): 246–247. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2012.09.010.

- ↑ Bonfils, K. A., Lysaker, P. H., Minor, K. S., & Salyers, M. P. (2017). "Empathy in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index". Psychiatry Research. 249: 293–303. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.12.033.

- ↑ Decety, J.; Michalska, K. J.; Akitsuki, Y.; Lahey, B. B. (2009). "Atypical empathic responses in adolescents with aggressive conduct disorder: A functional MRI investigation". Biological Psychology. 80: 203–211. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.09.004. PMC 2819310.

- ↑ Cheng, Y. W.; Hung, A. Y.; Decety, J. (2012). "Dissociation between affective sharing and emotion understanding in juvenile psychopaths. [Article]". Development and Psychopathology. 24 (2): 623–636. doi:10.1017/s095457941200020x.

- 1 2 Auyeung, K., & Alden, W. (2016). "Social Anxiety and Empathy for Social Pain". Cognitive Therapy and Research. 40 (1): 38–45. doi:10.1007/s10608-015-9718-0.

- ↑ Ruckman, J., Bodden, M., Jansen, A., Kircher, T., Dobel, R. & Reif, W. (2015). "How pain empathy depends on ingroup/outgroup decisions: A functional magnet resonance imaging study". Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 234 (1): 57–65. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.08.006.

- ↑ Feng, C., Li, Z., Feng, X., Wang, L., Tian, T., & Luo, Y. (2016). "Social hierarchy modulates neural responses of empathy for pain". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 11 (3): 485–495. doi:10.1093/scan/nsv135. PMC 4769637.

- ↑ Decety, J.; Yang, C. Y.; Cheng, Y. W. (2010). "Physicians down-regulate their pain empathy response: An event-related brain potential study. [Article]". NeuroImage. 50 (4): 1676–1682. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.025.

- ↑ Fitzgibbon, B. M.; Giummarra, M. J.; Georgiou-Karistianis, N.; Enticott, P. G.; Bradshaw, J. L. (2010). "Shared pain: From empathy to synaesthesia. [Review]". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 34 (4): 500–512. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.007.

- ↑ Atkins, D., Uskul, A., & Cooper, N. (2016). "ulture shapes empathic responses to physical and social pain". Emotion (Washington, D.C.). 16 (5): 587–601. doi:10.1037/emo0000162.