Orelhão

Orelhão (Big Ear), officially Telefone de Uso Público (Public Use Telephone)[1] is the name given to the protector for public telephones designed by Chinese Brazilian architect and designer Chu Ming Silveira. Created in April 4, 1972, initially in the cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.[2] Today, they are present everywhere in Brazil, in Latin American countries such as Peru, Colombia and Paraguay, in African countries like Angola and Mozambique, China and other parts of the world.

The challenge

Dated from the distant 1920s, it was the installation of the first public access telephones in Brazil. The population of the country then reached, back then, 30,635,605 inhabitants. Equipped with a coin box, adapted to a common apparatus, these semi-public telephones were found in commercial establishments that signed a contract with Companhia Telefônica Brasileira, a Canadian-owned company that was then responsible for telephony in the states of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais.

Real public telephones only reached Brazilian sidewalks in mid-1971, when more than 93 million people were living in the country and mobile phones were not created yet. Mobile telephony was just something imaginary and the first cell phone would only be released in 1973, accessible to very few.

Of the almost 100 million inhabitants of Brazil, 52 million lived in urban areas, according to IBGE data. The result is that in many places, listening and being heard from a public phone, installed in the middle of the street, was a real challenge. As a solution to the problem, CTB developed circular fiberglass and acrylic cabins and, to test the novelty, installed 13 of them in the city of São Paulo. The result did not please the company, that detected an inadequate use of the equipment, a high rate of vandalism and concluded that the spacious cabin, besides being muffled, ended up bothering the passersby, by filling the narrow space of the sidewalks.

In order to face this disappointing diagnosis, architect Chu Ming Silveira went on to work on the project that would result in one of the greatest icons of Brazilian design: the "Orelhão." The challenge was not small, as can be concluded from the detailed descriptive memo prepared by Chu Ming, who at that time headed the projects section of the Engineering Department of Brazilian Telephony Company. Design and acoustics suited to Brazilian climatic conditions were at the root of the problem and the solution proposed by Chu Ming would meet, with great success, the whole series of needs she had listed:

- Phone protection.

- User protection.

- Low manufacturing and maintenance cost.

- Low cost and simplicity of installation.

- Durability and resistance to weather, use and damage caused.

- Modularity to meet points of different concentrations.

- Good acoustics.

- Good aesthetics.

- Attractive to the public.

- Operational simplicity.

- Possibility of uninterrupted use.

- Design a good image of service to the public.

- Institution of one more element in the urban landscape.

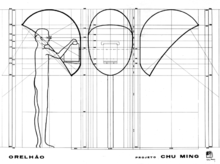

- Satisfy ergonometrically the statistical fashion of the Brazilian urban man.

The solution

To reach a sort of cabin made of fiberglass, strong, very light, resistant to sun, rain and fire and, according to newspapers of the time, "cheap," Chu Ming Silveira started with an egg shape, according to herself, "the best acoustic form." The curvature of the dome offered an acoustic protection of 70 to 90 decibels, provided the user was under it. Most of the noise reaching the shield was reflected out, the remainder converging to the center of the radius of curvature, located well below the ear of the average user, in order to minimize interference in communication.

Launched in 1972, a new booth, which would be quickly incorporated into Brazilian landscapes, although technically called by CTB of "Chu II" and later immortalized as "Orelhão," gained a number of curious nicknames. "Tulipa" and "Astronaut's Helmet" were some of them. The press adopted "Tulip," which referred to the format of the set of 2 or 3 devices attached to the ground by an iron pipe through which the wires ran. The orange and blue "tulips" were equipped with red telephone handsets produced in the Japanese city of Osaka, popularly called "reds" or "tamurinhas". For indoor environments, such as commercial engagements and public offices, Chu Ming developed the "Chu I" or "Orelhinha," before the Orelhão, smaller in orange acrylic. It could be installed on a wall or adapted to different supports, at a defined height from what would be an average of Brazilian men. The first ones were test in mid-1971, on the lobby of CBT's headquarters building, at Rua 7 de Abril, central region of São Paulo.

On January 20, the day of its patron saint Saint Sebastian, the city of Rio de Janeiro received the first Orelhões of the Brazilian Telephone Company. The newspaper O Diário de São Paulo reported on the anniversary of the city of São Paulo, on January 25, to announce the arrival of the new phones in the streets of the city:

"... And on this day, São Paulo wins a gift from the Brazilian Telephone Company: 170 telephone booths of a new model, christened "Tulipa" by its creator, the Chinese architect Chu Ming.[3]"

Keeping the commemorative tone, the text highlighted the quality of the design of said "Tulips," "in which the technique combines with environmental beauty." According to the CTB, there were then in São Paulo about 4,000 public telephones, while the ideal number to meet the demand would be 22,500. The success of Orelhão could be verified not only by the sympathy with which the population received it, but also by the increase of connections made from public telephones. In March 1972, CTB estimated that the installation of the new equipment would boost a 12% increase in the daily average of these calls.

The success

And the invention of Chu Ming gained admirers, eventually crossing the Atlantic in 1973. In a visit to Rio de Janeiro, the Secretary of Communications of Mozambique showed an interest in the equipment and the result was that three Orelhões "emigrated" to the African continent. And it didn't stop there. Today, Orelhão and adaptations of it are found in Latin American countries such as Peru, Colombia, Paraguay, and other African countries, such as Angola, and even in China, the roots of its idealizer.

In the same year of the first export operation of Brazilian telephone protectors, Telecomunicações de São Paulo S.A. (TELESP), of the Telebrás group, replaced CTB in the telephone operation in the state of São Paulo. And in 1975, the blue Orelhões arrived for long-distance calls.

The demands considered by Chu Ming Silveira in the Orelhão conception process seemed to be fully met, according to a comparative analysis of market research conducted for Telesp in 1977 and 1978: the public telephone service was considered excellent by 18.8% in 1977 and in the following year by 20.4%. Good for 36.4% in 1977 and 37.7% in 1978. The phones, according to the survey, were used by 82% of the population. 40% used it at least once a week. As for "modernity," in 1978, 73% agreed absolutely. 70% agreed that the Orelhões were "very presentable" and 66% said they were "well-placed".

But despite the expressive demonstration of recognition for utility and quality of service, acts of vandalism against the Orelhões were frequent and numerous. The enormous money loss caused to Telesp motivated the hiring of the publicist José Zaragoza, of the DPZ agency, to create in 1980 a film that would become an icon of Brazilian publicity. Using elements of police chronicle, the film "The Death of the Orelhão" caused a strong impact, when showing a device incapacitated to render service, victim of vandalism. Also as part of this effort to resist the vandals' attacks in April of the same year, Telesp invested in a new cabin format in concrete and colorless tempered glass. Initially tested in the cities of São Paulo, Santos, Guarujá, São Vicente and Campinas, and then installed throughout the state, the new protector was not well accepted.

In 1982, Telesp inaugurated the first community telephone in the Vila Prudente favela, a public telephone that received calls. The population grew stronger and stronger with the Orelhão, who made communication possible from the most distant and even unlikely places. A print advertisement in 1984 brought images of Orelhões in different geographic settings of Brazil: on the beach, in the mountains, in the typically rural area, on the side of a road. And the text emphasized, as follows, the companion character of the Orelhão: "Telesp always puts a friendly little ear near you. On the coast, in the estancias, on the roads, on the outskirts of São Paulo, in the streets, squares and avenues, you always find a friendly little ear to listen to you: Telesp's Orelhões."[4] But to enjoy the service it was necessary to have some phone coins in your pocket. These coins would be replaced by phone cards in 1992.

New colors, new times

On November 26, 1998, some Orelhões dawned on lime-green clothes, marking the acquisition of Telesp by Spanish company Telefónica, as part of the privatization process that affected 11 other companies resulting from the Telebrás division.

New fiberglass totems were launched by the company in 1999, but the Orelhão continued through the streets, being part of the daily life of Brazil. Currently, in the state of São Paulo, there are 210,000 of them, according to Telefónica. But the trend is that this number will decrease, due to the resolution of Anatel, which reduced the minimum requirement for handsets, from 6 to 4 per thousand inhabitants, in cities throughout Brazil. Also the advance of mobile telephony has been contributing to the loss of space of the public telephones. In December 2011, there were about 143 mobile handsets per 100 inhabitants in the state of São Paulo.

At the beginning of 2012, there were 247,6 million cell phones throughout Brazil. At the same time, a survey by Telefónica found that the sale of phone cards fell 45% in the state of São Paulo, compared to the first half of 2011. The company has decided to deactivate the "Tulips" of the 70s, but it must conserve handsets to ensure that the user does not have to walk more than 300 meters to have access to one of these long-standing companions.

In her 70s almanaque, "Memories and Curiosities of a Very Mad Decade", journalist and writer Ana Maria Bahiana places the arrival of the Metro, the Portable Calculator and the Computer in Brazil, The Sports Lottery and the Orelhão among the wonders of modernity at that time.

Already in the 21st century, even though it loses its space as a telephone communication tool, Orelhão, fully incorporated into street furniture, reaches its 40th anniversary and has guaranteed its status as a world design icon, symbol of Brazil.

See also

References

- ↑ Teleco – Telefone de Uso Público – TUP (Orelhão)

- ↑ www.orelhao.arq.br Official website of Orelhão and of its inventor Chu Ming Silveira

- ↑ O Diário de São Paulo, Sunday, January 23, 1972.

- ↑ Revista Veja, nº 827, July 11, 1984.