Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts

|

| Part of a series on the |

| French language |

|---|

| History |

| Grammar |

| Orthography |

| Phonology |

|

The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts (French: Ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts) is an extensive piece of reform legislation signed into law by Francis I of France on August 10, 1539 in the city of Villers-Cotterêts and the oldest French legislation still used partly by French courts.

Largely the work of Chancellor Guillaume Poyet, the legislative edict had 192 articles and dealt with a number of government, judicial and ecclesiastical matters (ordonnance générale en matière de police et de justice).

Articles 110 and 111

Articles 110 and 111, the most famous, and the oldest still in use in the French legislation, called for the use of French in all legal acts, notarised contracts and official legislation to avoid any linguistic confusion:

CX. Que les arretz soient clers et entendibles. Et afin qu'il n'y ayt cause de doubter sur l'intelligence desdictz arretz. Nous voulons et ordonnons qu'ilz soient faictz et escriptz si clerement qu'il n'y ayt ne puisse avoir aulcune ambiguite ou incertitude, ne lieu a en demander interpretacion.

CXI. De prononcer et expedier tous actes en langaige françoys Et pour ce que telles choses sont souventesfoys advenues sur l'intelligence des motz latins contenuz es dictz arretz. Nous voulons que doresenavant tous arretz ensemble toutes aultres procedeures, soient de nous cours souveraines ou aultres subalternes et inferieures, soient de registres, enquestes, contractz, commisions, sentences, testamens et aultres quelzconques actes et exploictz de justice ou qui en dependent, soient prononcez, enregistrez et delivrez aux parties en langage maternel francoys et non aultrement.

110. That decrees be clear and understandable. And in order that there may be no cause for doubt over the meaning of the said decrees. We will and order that they be composed and written so clearly that there be not nor can be any ambiguity or uncertainty, nor grounds for requiring interpretation thereof.

111. On pronouncing and drawing up all legal documents in the French language. And because so many things often hinge on the meaning of Latin words contained in the said documents. We will that from henceforth all decrees together with all other proceedings, whether of our royal courts or others subordinate or inferior, whether records, surveys, contracts, commissions, awards, wills, and all other acts and deeds of justice or dependent thereon be spoken, written, and given to the parties in the French mother tongue and not otherwise.

Goals

The major goal of these articles was to discontinue the use of Latin in official documents (although Latin continued to be used in church registers in some regions of France), but they also had an effect on the use of the other languages and dialects spoken in many regions of France.

Other articles required that priests record baptisms (needed for determining the age of candidates for ecclesiastical office) and burials, and that these acts be signed by notaries.

Another article prohibited guilds and trade federations (toute confrérie de gens de métier et artisans) in an attempt to suppress workers' strikes (although mutual-aid groups were unaffected).

Effects

Many of these clauses marked a move towards an expanded, unified and centralized state and the clauses on the use of French marked a major step towards the linguistic and ideological unification of France at a time of growing national sentiment and identity.

Despite the effort to bring clarity to the complex systems of justice and administration prevailing in different parts of France and to make them more accessible, Article 111 left uncertainty in failing to define the French mother tongue. Many varieties of French were spoken around the country, to say nothing of sizeable regional minorities like Bretons and Basques whose mother tongue was not French at all.

It was not until 1794 that the government decreed French to be the only language of the state for all official business,[1] a situation still in force under Article 2 of the 1992 Constitution.[2]

See also

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Sachsenspiegel, c. 1220, first legal document written in German rather than Latin

- Pleading in English Act 1362, English law mandating use of English instead of French in oral argument in court

- Proceedings in Courts of Justice Act 1730, British law mandating use of English instead of Latin in court writing

Gallery

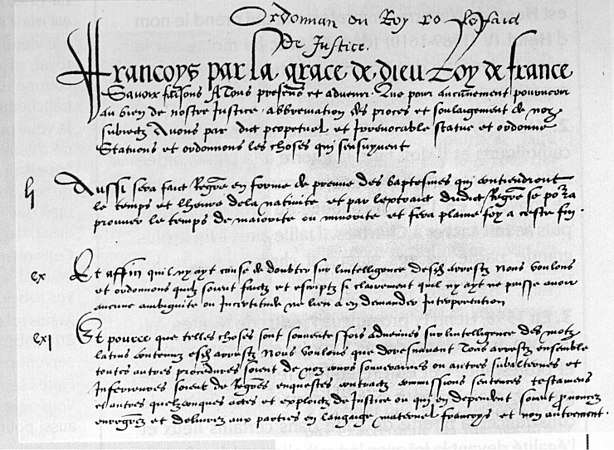

The first manuscript page of the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, 1539.

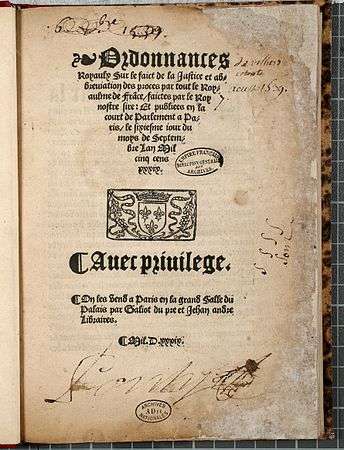

The first manuscript page of the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, 1539. Title page of the printed version of the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, August 1539.

Title page of the printed version of the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, August 1539. Printed version of article 111 of the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, prescribing the use of French in official documents.

Printed version of article 111 of the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, prescribing the use of French in official documents.