Operation Boomerang

Operation Boomerang was an unsuccessful air raid conducted by the United States Army Air Forces' (USAAF) XX Bomber Command against oil refining facilities in Japanese-occupied Palembang on the night of 10/11 August 1944 during World War II. A total of 54 heavy bombers were dispatched from an airfield in Ceylon, of which 39 reached the target area. Attempts to bomb an oil refinery were unsuccessful, with only a single small building being confirmed destroyed. Mines dropped in the river which connects Palembang to the sea sank three ships and damaged two others. British forces provided search and rescue support for the American bombers. This was the only USAAF attack on the strategically important oil facilities at Palembang.

Background

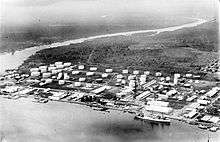

At the time of the Pacific War, the Sumatran city of Palembang in the Netherlands East Indies was a major oil production center. The city and its oil refineries were captured by Japanese forces in mid-February 1942 during the Battle of Palembang.[1] In early 1944, Allied intelligence estimated that the Pladjoe refinery at Palembang was the source of 22 percent of Japan's fuel oil for ships and industrial facilities, and 78 percent of its aviation gasoline.[2]

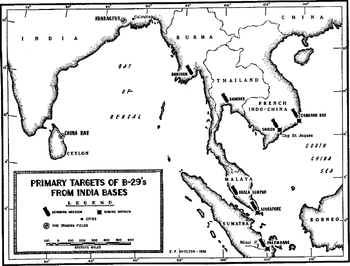

In late 1943, the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff approved a proposal to begin the strategic air campaign against the Japanese home islands and East Asia by basing Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers in India and establishing forward airfields in China. The main element of this strategy, designated Operation Matterhorn, was to construct airstrips near Chengdu in inland China which would be used to refuel B-29s travelling from bases in Bengal en route to targets in Japan. Operation Matterhorn was to be conducted by the Twentieth Air Force's XX Bomber Command. Unusually, the head of the USAAF, General Henry H. Arnold, also served as the head of the Twentieth Air Force. Brigadier General Kenneth Wolfe led XX Bomber Command.[3] XX Bomber Command conducted its first combat mission against Bangkok on 5 June 1944. During this operation, two B-29s ran out of fuel during the return flight to India over the Bay of Bengal and were forced to ditch.[4][5]

Planning

The attack on Palembang arose from debates which preceded the approval of Operation Matterhorn concerning how to best employ the B-29s. During late 1943 and early 1944, serious consideration was given to initially using the B-29s to attack merchant shipping and oil facilities in South East Asia from bases in northern Australia and New Guinea.[6] The final plan for Operation Matterhorn approved by the Joint Chiefs of Staff in April specified that while XX Bomber Command was to focus on Japan, it would also attack Palembang. These raids were to be staged through airfields in Ceylon.[7] The inclusion of Palembang in the plan represented a compromise between the strategists who wanted to concentrate the force against Japan and those who wished to focus it on oil targets. For planning purposes, the date for the first attack on Palembang was set at 20 July 1944.[8]

An airfield capable of accommodating B-29s was prepared to support the planned raids on Palembang. In March 1944, work began on modifying four airfields on Ceylon to the standards needed for B-29s, with RAF China Bay and RAF Minneriya being accorded the highest priority. These two airfields were scheduled to be ready by July, but in April it was decided to concentrate on China Bay when it became apparent that both could not be completed in time. By mid-July China Bay was capable of accommodating 56 B-29s but still required some further work.[9]

Shortly after XX Bomber Command's first attack on Japan, made against Yawata on the night of 15/16 June, Arnold pressed Wolfe to attack Palembang as part of the follow-up raids. In his reply, Wolfe noted that it would not be possible to conduct the attack until the airfield at China Bay was ready on 15 July. Arnold issued XX Bomber Command with a new targeting directive on 27 June which specified that 50 B-29s be dispatched against Palembang as soon as the airfield was complete. Wolfe was transferred to a role in the United States on 4 July. Brigadier General LaVern G. Saunders took over the command on a temporary basis.[10] Saunders decided to delay the attack on Palembang until mid-August to enable XX Bomber Command to first make a maximum effort raid on Anshan in China, which Arnold had accorded the highest priority.[11]

Preparations

United States

Planning for the attack on Palembang began in May 1944.[2] Due to the very long distance which was to be flown and the need to stage through Ceylon, the operation required more planning and preparations than any of the other raids conducted by XX Bomber Command.[12] USAAF and Royal Air Force personnel worked together to complete the preparations. The British supplied fuel for the operation and met the costs of upgrading the Ceylon airfields under Reverse Lend-Lease arrangements. RAF China Bay, including its accommodation facilities and transport vehicles, was virtually given over to the USAAF. The RAF also donated whisky rations to the Americans.[13]

The plans for the operation evolved over time. The Twentieth Air Force initially ordered that the attack involve all 112 of XX Bomber Command's aircraft, and be conducted during the day. The Command sought to have this directive modified on the grounds that dispatching so many aircraft from a single airfield would mean that the force would need to be separated into several waves. Splitting the force in this way would further complicate the operation, and was considered likely to lead to higher losses. Arnold accepted this argument, and his 27 June targeting directive specified that the attack take place either at dawn or dusk and involve at least 50 aircraft.[13] The meteorologist assigned to the operation recommended that the attack be made at night so that the B-29s could take advantage of favourable tailwinds.[14] XX Bomber Command gained the Twentieth Air Force's agreement for this change.[15]

During the period in which the plan was prepared, several US intelligence agencies altered their views regarding the importance of Palembang. The USAAF's Assistant Chief of Air Staff, Intelligence and the Committee of Operations Analysts judged that the changing tactical situation in the Pacific and heavy losses of Japanese shipping meant that the Pladjoe refinery was no longer of critical importance to the Japanese war effort. XX Bomber Command staff would have liked to have cancelled the mission, which they viewed as a distraction from the main effort against the Japanese steel industry. The Joint Chiefs of Staff continued to require that Palembang be attacked, however, and Arnold included it in another target directive issued in July. After it was confirmed that the facilities at China Bay would be complete by 4 August, Arnold directed that the raid be conducted by the 15th of the month. The date for the attack was set as 10 August.[2]

Several targets were specified. The primary target was the Pladjoe refinery and the secondary target the nearby Pangkalan refinery. The Indarung Cement Plant at Padang was the last resort target for aircraft unable to reach Palembang. In addition, part of the force was tasked with dropping naval mines to block the Moesi River through which all the oil produced at Palembang was shipped.[13] Due to the extreme range from Ceylon to the targets and back (3,855 miles (6,204 km) to Palembang and 4,030 miles (6,490 km) to the Moesi), the bombers were to be loaded with only a ton of bombs or mines each and have their fuel tanks filled to capacity.[16] Planning for the attack was completed on 1 August.[15] It was designated Operation Boomerang, possibly in the hope that all of the aircraft would return from their long flights.[16]

An attack by XX Bomber Command on the Japanese city of Nagasaki was scheduled to take place on the same night as the raid on Palembang.[17] The USAAF official history states that it was hoped that attacking two targets 3,000 miles (4,800 km) apart would have a psychological impact on the Japanese.[18]

Japanese

The Imperial Japanese Army was responsible for defending the oil fields on Sumatra against air attack. The Palembang Air Defense Headquarters had been formed in March 1943 for this purpose, and initially comprised the 101st, 102nd and 103rd Air Defense Regiments and the 101st Machine Cannon Battalion. Each of the Air Defense Regiments was equipped with 20 Type 88 75 mm AA guns. They may have also each included a machine cannon battery and a searchlight battery.[19]

In January 1944 the 9th Air Division was established as part of efforts to strengthen Sumatra's air defenses. By this time the Palembang Air Defense Headquarters had been redesignated the Palembang Defense Unit.[20] This unit was expanded to include both fighter aircraft and antiaircraft gun units. The 21st and 22nd Fighter Regiments of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force were responsible for intercepting Allied aircraft. The 101st, 102nd and 103rd Antiaircraft Regiments and 101st Machine Gun Cannon remained, and had been supplemented by the 101st Antiaircraft Balloon Regiment which operated barrage balloons.[21]

Attack

On the afternoon of 9 August, 56 B-29s from the 444th and 468th Bombardment Groups arrived at RAF China Bay.[15][22] The strike force began to take off from China Bay at 4:45 PM on 10 August. A total of 54 B-29s were dispatched. While one of the aircraft returned to base 40 minutes into its flight due to engine problems, it was repaired within two hours, and took off again bound for Sumatra.[15]

The bombers' journey to Sumatra was uneventful. The aircraft flew individually on a direct course from China Bay to Siberoet island off the west coast of Sumatra. Upon reaching Siberoet, the bombers changed course, and headed for the Palembang area.[15] Several British warships from the Eastern Fleet and RAF aircraft were positioned along this route throughout to rescue the crews of any B-29s which were forced to ditch. These included the light cruiser HMS Ceylon, destroyer Redoubt and submarines Terrapin and Trenchant. The submarines were also used as navigation beacons.[1][23]

A total of 31 B-29s attempted to bomb the Pladjoe refinery. It proved difficult for their crews to locate the target, as no lights were showing in Palembang, patchy cloud covered the area and the bomber which had been tasked with illuminating the refinery with flares did not reach the area. Instead, the bombardiers aimed their bombs using radar or visual sightings through breaks in the clouds. American airmen reported seeing some explosions and fires, but strike photos taken from the bombers were indistinct.[15] Eight B-29s descended below the clouds to drop two mines each in the Moesi River; the accuracy of this attack was considered "excellent".[15] This was the first time B-29s had been used as mine layers.[24]

Of the fifteen B-29s which failed to reach the Palembang area, three attacked other targets. A pair of B-29s bombed the oil town of Pangkalanbrandan in northern Sumatra and another struck an airfield near the town of Djambi.[15]

Japanese forces fired on the B-29s in the Palembang area, but without success. Anti-aircraft guns and rockets were fired at the bombers, and the American airmen sighted 37 Japanese aircraft. None of the B-29s were damaged.[15]

One of the B-29s ditched into the sea 90 miles (140 km) from China Bay on its return flight. Its crew were able to send a SOS signal before ditching, which led to Allied forces conducting an intensive search of the area. One of the bomber's gunners was killed in the accident, and the other members of the crew were rescued on the morning of 12 August.[16] These were the only Allied losses in the operation.[1]

Aftermath

Operation Boomerang was not successful. Photos taken of the Pladjoe refinery on 19 September indicated that only a single building had definitely been destroyed in the raid, though several others were assessed as "probables".[16] The mines produced better results, as they sank three ships, damaged two others and prevented oil from being transported via the Moesi River for a month.[1][Note 1] Despite the failure of Operation Boomerang to achieve its goals, it demonstrated that XX Bomber Command was now capable of conducing complex operations and the B-29s could safely travel long distances over water.[16]

XX Bomber Command continued to be reluctant to attack Palembang, and recommended to the Twentieth Air Force on 24 August that China Bay be abandoned. Approval to do so was granted on 3 October, though the Twentieth Air Force directed that the aircraft fuelling system remain in place. No other B-29 attacks were conducted through Ceylon. The USAAF official history noted that developing the base for only a single operation was "a glaring example of the extravagance of war".[16]

The British Eastern Fleet's aircraft carriers conducted several raids on oil facilities in Sumatra between November 1944 and January 1945. These included two raids against Palembang conducted as part of Operation Meridian in January 1945. On 24 January the fleet's aircraft badly damaged the Pladjoe refinery, and on the 29th of the month serious damage was inflicted on the nearby Sungei Gerong refinery.[1]

See also

References

Footnotes

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hackett 2016.

- 1 2 3 Craven & Cate 1953, p. 108.

- ↑ Correll 2009, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Craven & Cate 1953, p. 97.

- ↑ Mann 2009, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Craven & Cate 1953, p. 28.

- ↑ Craven & Cate 1953, p. 31.

- ↑ Craven & Cate 1953, pp. 71, 93.

- ↑ Craven & Cate 1953, p. 73.

- ↑ Craven & Cate 1953, p. 103.

- ↑ Craven & Cate 1953, p. 105.

- ↑ Craven & Cate 1953, pp. 107–108.

- 1 2 3 Craven & Cate 1953, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Fuller 2015, p. 113.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Craven & Cate 1953, p. 109.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Craven & Cate 1953, p. 110.

- ↑ Craven & Cate 1953, pp. 111.

- ↑ Craven & Cate 1953, pp. 109, 111.

- ↑ Ness 2014, p. 317.

- ↑ Headquarters United States Army Japan 1959, p. 168.

- ↑ Ness 2014, p. 330.

- ↑ Mann 2009, p. 40.

- ↑ Rohwer 2005, p. 348.

- ↑ Rohwer 2005, p. 349.

Works consulted

- Correll, John T. (March 2009). "The Matterhorn Missions". Air Force Magazine. pp. 62–65. ISSN 0730-6784.

- Craven, Wesley; Cate, James, eds. (1953). The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki. The Army Air Forces in World War II. Volume V. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. OCLC 256469807.

- Fuller, John (2015). Thor's Legions: Weather Support to the U.S. Air Force and Army, 1937-1987. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 9781935704140.

- Hackett, Bob (2016). "Oil Fields, Refineries and Storage Centers Under Imperial Japanese Army Control". combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- Headquarters United States Army Japan (1959). Japanese Monograph No. 45 : History of Imperial General Headquarters Army Section (Revised Edition). HyperWar Project.

- Mann, Robert A. (2009). The B-29 Superfortress Chronology, 1934-1960. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 9780786442744.

- Naval Analysis Division (1946). The Offensive Mine Laying Campaign Against Japan. Washington, D.C.: The United States Strategic Bombing Survey. OCLC 251177565.

- Ness, Leland S. (2014). Rikugun: Guide to Japanese Ground Forces, 1937–1945. Volume 1: Tactical Organization of Imperial Japanese Army & Navy Ground Forces. Solihull, United Kingdom: Helion. ISBN 9781909982000.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939-1945: The Naval History of World War Two. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1591141192.