No-fly zone

A no-fly zone or no-flight zone (NFZ), or air exclusion zone, is a territory or an area over which aircraft are not permitted to fly. Such zones are usually set up in a military context, somewhat like a demilitarized zone in the sky, and usually prohibit military aircraft of a belligerent power from operating in the region. Aircraft that break the no-fly zone may be shot down, depending on the terms of the NFZ. Air exclusion zones and anti-aircraft defences are sometimes set up in a civilian context, for example to protect sensitive locations, or events such as the 2012 London Olympic Games, against terrorist air attack.

No-fly zones are a modern phenomenon. They can be distinguished from traditional air power missions by their coercive appropriation of another nation’s airspace only, to achieve aims on the ground within the target nation. While the Royal Air Force (RAF) conducted prototypical air control operations over contentious colonial possessions between the two World Wars of the 20th century, no-fly zones did not assume their modern form until the end of the Persian Gulf War in 1991.[1]

During the Cold War, the risk of local conflict escalating into nuclear showdown dampened the appeal of military intervention as a tool of U.S. statecraft. Perhaps more importantly, air power was a relatively blunt instrument until the operational maturation of stealth and precision-strike technologies. Before the Gulf War of 1991, air power had not demonstrated the “fidelity” needed to perform nuanced attacks against transitory, difficult-to-reach targets—it lacked the ability to produce decisive political effects short of total war. However, the demise of the Soviet Union and the rise in aerospace capabilities engendered by the technology revolution made no-fly zones viable in both political and military contexts.[1]

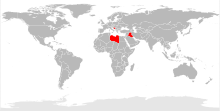

Past no-fly zones

Iraq, 1991–2003

In 1991, the United States, United Kingdom, France, Turkey, and other states intervened in Kurdish-Iraqi dispute in northern Iraq by establishing a no-fly zone in which Iraqi aircraft were prevented from flying. The intent of the no-fly zone was to prevent possible bombing and chemical attacks against the Kurdish people by the Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein. The initial operations were dubbed Operation Provide Comfort and Operation Provide Comfort II and were followed by Operation Northern Watch. While the enforcing powers had cited United Nations Security Council Resolution 688 as authorizing the operations, the resolution contains no explicit authorization. The Secretary-General of the UN at the time the resolution was passed, Boutros Boutros-Ghali called the no-fly zones "illegal" in a February 2003 interview with John Pilger.[2][3] In southern Iraq, Operation Southern Watch was established in 1992 to protect Iraq's Shia population. It originally extended to the 32nd parallel[4] but was extended to the 33rd parallel in 1996.[5]

Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1993–1995

In 1992, the United Nations Security Council passed United Nations Security Council Resolution 781, prohibiting unauthorized military flights in Bosnian airspace. This led to Operation Sky Monitor, where NATO monitored violations of the no-fly zone but did not take action against violators of the resolution. In response to 500 documented violations by 1993,[6] including one combat violation,[7] the Security Council passed Resolution 816, which prohibited all unauthorized flights and allowed all UN member states to "take all necessary measures...to ensure compliance with [the no-fly zone restrictions]."[8] This led to Operation Deny Flight. NATO later launched air strikes during Operation Deny Flight and during Operation Deliberate Force.

Lessons from Iraq and Bosnia

A 2004 Stanford University paper published in Journal of Strategic Studies, "Lessons from Iraq and Bosnia on the Theory and Practice of No-fly Zones," reviewed the effectiveness of the air-based campaigns in achieving military objectives. The paper's findings were: 1) A clear, unified command structure is essential. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, during "Operation Deny Flight," a confusing dual-key coordination structure provided inadequate authority and resulted in air forces not being given authority to assist in key situations; 2) To avoid a "perpetual patrol problem," states must know in advance their policy objectives and the exit strategy for no-fly zones; 3) The effectiveness of no-fly zones is highly dependent on regional support. A lack of support from Turkey for the 1996 Iraq no-fly zone ultimately constrained the coalition's ability to effectively enforce it.[9]

Libya, 2011

As part of the 2011 military intervention in Libya, the United Nations Security Council approved a no-fly zone on 17 March 2011. The resolution includes provisions for further actions to prevent attacks on civilian targets.[10][11] NATO seized the opportunity to take the offensive, bombing Libyan government positions during the civil war. The NATO no fly zone was terminated on 27 October after a unanimous vote by the UNSC.[12]

Civilian Example

Concerns about possible air attacks on the 2012 Olympic Games in London led to many precautions and layers of protection, including airspace zones that could be entered only with permission.[13] No-fly zones are often put in place for events such as the 2017 G20 Hamburg summit.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 "Air Exclusion Zones: An Instrument for Engagement in a New Century," Brig General David A. Deptula, in "Airpower and Joint Forces: The Proceeding of a Conference Held In Canberra by the RAAF, 8–9 May 2000," "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ↑ Pilger, John (February 23, 2003). "A People Betrayed" Archived 2007-11-14 at the Wayback Machine.. ZNet. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ↑ Pilger, John (August 7, 2000). "Labour Claims Its Actions Are Lawful While It Bombs Iraq, Strarves Its People and Sells Arms To Corrupt States". johnpilger.com. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ↑ Staff writer (December 29, 1998). "Containment: The Iraqi No-Fly Zones". BBC News. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ↑ 2nd Cruise Missile Strikes in Iraq Archived 2005-02-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Beale, Michael (1997). Bombs over Bosnia – The Role of Airpower in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Air University Press (Maxwell Air Force Base, Montgomery, Alabama). p. 19. OCLC 444093978.

- ↑ Lewis, Paul (March 19, 1993). "U.N. Moving To Toughen Yugoslav Flight Ban". The New York Times. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ↑ Resolution (March 31, 1993). "Resolution 816 (1993) – Adopted by the Security Council at Its 3191st Meeting, on 31 March 1993". United Nations Security Council (via The UN Refugee Agency). Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ↑ "Lessons from Iraq and Bosnia on the Theory and Practice of No-fly Zones". Journalist's Resource.org.

- ↑ Bilefsky, Dan; Landler, Mark (March 17, 2011). "U.N. Approves Airstrikes to Halt Attacks by Qaddafi Forces". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Security Council Approves ‘No-Fly Zone’ over Libya, Authorizing ‘All Necessary Measures’ to Protect Civilians, by Vote of 10 in Favour with 5 Abstentions"

- ↑ UN votes to end no-fly zone over Libya , Aljazeera, October 28, 2011.

- ↑ "UK Armed Forces Enforce Olympic Airspace Limits". Armed Forces International. 13 July 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-10-29. Retrieved 2017-07-14.

References

- Bass, Frank; Solomon, John (April 5, 2002). "Prohibited Flights Not Unusual – Preventing Terrorism on Capital Poses Challenge". Associated Press (via Lawrence Journal-World). Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- No-Fly Zones: Strategic, Operational, and Legal Considerations for Congress Congressional Research Service

- Wheeler, Nicholas J. (2000) Saving Strangers – Humanitarian Intervention in International Society. Oxford University Press (Oxford, England). ISBN 978-0-19-829621-8.