Nipigon River Bridge

| Nipigon River Bridge (2015) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 49°01′11″N 88°15′01″W / 49.0196°N 88.2504°WCoordinates: 49°01′11″N 88°15′01″W / 49.0196°N 88.2504°W |

| Carries | 2 lanes of Trans-Canada Highway ( Highway 11 / Highway 17) |

| Crosses | Nipigon River |

| Locale | Nipigon, Ontario |

| Maintained by | Ministry of Transportation of Ontario |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Cable-stayed |

| Total length | 252 metres (827 ft)[1] |

| Width | 37 metres (121 ft)[2] |

| Height | 75 metres (246 ft)[2] |

| No. of spans | 2 |

| History | |

| Architect | Marshall Macklin Monaghan (MMM) |

| Constructed by | Bot Construction and Ferrovial Agroman |

| Construction start | 2013 |

| Construction end | 2018 (estimated) |

| Construction cost | $106 million |

| Opened | November 29, 2015 (westbound bridge) |

| Replaces | Nipigon River Bridge (1937, 1974) |

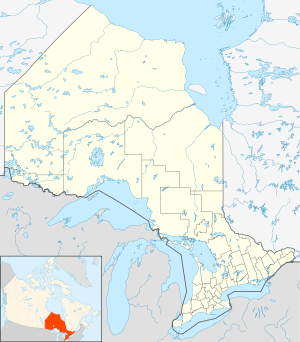

Nipigon River Bridge Location in Ontario | |

The Nipigon River Bridge is a cable-stayed bridge carrying Highway 11 and Highway 17, designated as part of the Trans-Canada Highway, across the Nipigon River near Nipigon, Ontario, Canada.

A steel deck truss road bridge was built at the site in 1937,[3] parallel to an existing Canadian Pacific Railway bridge. In 1974, the original bridge was replaced with a steel plate girder structure.[4]

Among the several points on the Trans-Canada Highway with only one crossing, all of which are in Northwestern Ontario, the two-lane Nipigon River Bridge was the longest.[5]

A $106 million project to replace the bridge with two parallel spans carrying four total lanes began in 2013 as part of a region-wide project to widen the Trans-Canada Highway to four lanes; the cable-stayed design for the twin bridges was to be the first of its kind in Ontario. The future westbound bridge opened on November 29, 2015; both directions of traffic were shifted onto the new bridge to prepare the old span for demolition. The eastbound span was scheduled for completion in 2017.[6][7]

Closure of new bridge

The bridge is asymmetric, with a longer eastern span, so the western side of the bridge must be held down to balance the tension in the main cables. This is done using three sliding bearings which hold main deck girders down to the concrete abutment while allowing lengthwise motion to act as an expansion joint.

On January 10, 2016, the new bridge was closed to traffic after all 40 M22 (7⁄8″) bolts attaching a main deck girder to the northwest bearing failed, causing the deck to lift by 60 centimetres (24 in) after a winter storm,[8] and resulting in the indefinite closure of the Trans-Canada Highway at the bridge.[9][10][11] As the bridge is a single point of failure in Canada's National Highway System, its closure effectively required vehicles travelling between Eastern and Western Canada to detour through the United States.[9] The deputy mayor of Greenstone, located 125 kilometres (78 mi) northeast of the bridge, declared a state of emergency for the municipality as a result of the closure.[11][12]

The bridge was partially reopened to traffic the following morning after 17 hours of closure, using one lane alternating between directions. The Ministry of Transportation inspected the bridge for further damage and determined that it would be able to handle cars and regular-weight transport trucks in the interim. 200 metric tons (200 long tons; 220 short tons) of concrete Jersey barriers were placed to weigh down the deck.[13][14]

It was estimated that over $100 million of goods per day shipped within Canada by truck were delayed by the bridge closure.[15]

A temporary fix was performed, consisting of a hold-down support system securing the steel girders to the bridge structure with a hanger system.[16] The bridge fully reopened to one lane in each direction on February 25, 2016, despite the exact cause of the failure not being fully known at the time.[17]

Demolition of the old bridge and construction of the second span also resumed in February 2016.[18]

On September 22, 2016, the Ministry of Transportation released several reports on the technical causes of the January 10, 2016 bearing failure.[19] Two reports, from Surface Science Western and the National Research Council, were released pertaining solely to the analysis of the failed bolts connecting the bearing to the bridge girders. They both found that the bolts met all required standards and they failed progressively due to severe overloading beyond their capacities.[20] The second component of the analysis involved an engineering evaluation, undertaken by ministry bridge engineers and an independent engineering consultant. They both found that there were three main causes for the failure:[21]

- The shoe plate, which connects the bearing to the girder, was too flexible—creating "prying action"[22] which amplified the forces on some bolts,

- The bearings could not properly rotate to accommodate non-parallelism between the deck girders and the concrete abutment, increasing the load on one end of the bearing, and

- The bolts were not properly tightened, subjecting the bolts to fatigue.

The ministry also revealed that the permanent repair to the bridge would involve a "linkage" system that would hold down the bridge and allow horizontal movements due to thermal expansion and contraction of the bridge superstructure.[21]

References

- ↑ "Nipigon River Bridge: Creating Ontario's First Cable-Stayed Bridge". Hatch Mott MacDonald. Archived from the original on April 15, 2016. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- 1 2 O'Reilly, Dan (February 27, 2015). "New Nipigon River Bridge a Trailblazing Project". Daily Commercial News. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ↑ Bevers, Cameron. "Photographic History of King's Highway 17". The King's Highway. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ Bevers, Cameron. "Photographic History of King's Highway 11". The King's Highway. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ Young, Leslie (January 11, 2016). "The Nipigon River Bridge and Other Trans-Canada Bottlenecks". Global News. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Ontario Reaches Milestone in Construction of Nipigon River Bridge" (Press release). Ministry of Northern Development and Mines. November 27, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Traffic Flows Across New Nipigon Bridge". The Chronicle-Journal. Thunder Bay, Ontario. November 29, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ↑ Hasham, Alyshah (January 10, 2016). "Trans-Canada Highway Bridge Linking East and West Partially Reopened". Toronto Star. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- 1 2 "New Nipigon Bridge Crippled". The Chronicle-Journal. Thunder Bay, Ontario. January 10, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Bridge Closure Blocks Trans-Canada Highway: Main Way to Cross Canada by Car Now Through U.S." National Post. Toronto. January 10, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- 1 2 Husser, Amy (January 10, 2016). "Ontario's Nipigon River Bridge Fails, Severing Trans-Canada Highway". CBC News. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Greenstone Declares State of Emergency" (Press release). Office of the Deputy Mayor of Greenstone. January 10, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Ontario's Nipigon River Bridge Opens to 1 Lane After Piece of Decking Lifts". CBC News. January 11, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ↑ McQuigge, Michelle (January 11, 2016). "Northern Ontario's Nipigon River Bridge Partially Reopens to Traffic". Global News. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Nipigon River Bridge Delays Slow $100M of Goods Shipped Daily". CBC News. January 13, 2016. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ↑ "MTO Releases Renderings of Nipigon Bridge Repairs". Today's Trucking. February 22, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Nipigon River Bridge Now Fully Open, but Remains Construction Zone". CBC News. February 25, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Nipigon River Bridge Construction Resumes". CBC News. February 29, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Component Design, Improperly Tightened Bolts Blamed for Nipigon River Bridge Failure". CBC News. September 22, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ↑ "Nipigon River Bridge: Bolt Testing" (PDF). Ministry of Transportation of Ontario. September 22, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- 1 2 "Update on the Nipigon River Bridge: Engineering Issues Cause Failure". My Algoma. September 22, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ↑ Kulak, Geoffrey L.; Fisher, John W.; Struik, John H. A. (2001). Guide to Design Criteria for Bolted and Riveted Joints (PDF) (2nd ed.). Research Council on Structural Connections. pp. 266–282. Retrieved September 24, 2016.