Nevile Henderson

| Sir Nevile Henderson GCMG | |

|---|---|

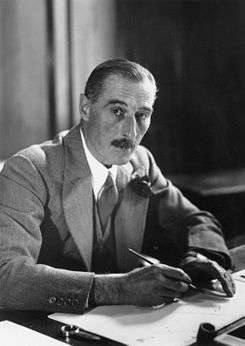

Ambassador Henderson in office, May 1937 | |

| Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia | |

|

In office 21 November 1929 – 1935 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | Sir Howard William Kennard |

| Succeeded by | Sir Ronald Ian Campbell (1939) |

| Ambassador to Argentina | |

|

In office 1935–1937 | |

| Monarch |

George V (1935–36) Edward VIII (1936) George VI (1936–37) |

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | Sir Henry Chilton |

| Succeeded by | Sir Esmond Ovey |

| Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Germany | |

|

In office 28 May 1937 – 7 September 1939 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Sir Eric Phipps |

| Succeeded by | General Sir Brian Robertson (1949) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

10 April 1882 Sedgwick, Sussex, England |

| Died |

30 December 1942 (aged 60) |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Education | Eton College |

Sir Nevile Meyrick Henderson GCMG (10 June 1882 – 30 December 1942) was a British diplomat and Ambassador of the United Kingdom to Nazi Germany from 1937 to 1939.

Life and career

He was born at Sedgwick Park near Horsham, Sussex, the third child of Robert and Emma Henderson.[1] His uncle was Reginald Hargreaves, who married Alice Liddell, the original of Alice in Wonderland. [2] Henderson was very attached to the countryside of Sussex, especially his hometown of Sedgwick, writing in 1940: "Each time that I returned to England the white cliffs of Dover meant Sedgwick for me, and when my mother died in 1931 and my home was sold by my elder brother's wife, something went out of my life which nothing can replace".[3] Henderson was extremely close to his mother Emma, a strong-willed woman who had successfully managed the estate at Sedgwick after her husband's death in 1895 and who developed the gardens of Sedgwick so well that they were photographed by the Country Life magazine in 1901.[3] Henderson called his mother "the presiding genius of Sedgwick" who was a "wonderful and masterful woman if ever there was one".[3]

He was educated at Eton and joined the Diplomatic Service in 1905. Henderson saw himself as a member of "the Establishment", and had the typical views of an upper-class Victorian Englishman, convinced of the superiority of all things British and seeing the British Empire as the greatest force for the good.[4] Henderson had a great love of sports, guns, and hunting and those who knew him noted he was always most happy when he was out on the hunt.[4] Henderson was also known for his love of clothing, always wearing the most expensive Savile Row suits and a red carnation, being considered to be one of the most best dressed men in the Foreign Office.[4] Henderson's obsession with his wardrobe, social etiquette, and hunting was part of a carefully cultivated image that he sought for himself as a polished "English gentleman".[4] Henderson never married, but his biographer, Peter Neville, wrote "women played an important role in his life".[4] Henderson's lifelong bachelorhood did not cause questions about his sexuality with Baron Ernst von Weizsäcker, the State Secretary of the Auswärtiges Amt, writing in his diary that Henderson was a "ladies's man".[4]

In the early 1920s, Henderson was stationed at the embassy in Turkey, where he played a major role in the often difficult relations between Britain and the new Turkish republic.[5] Henderson had wanted a posting in France rather than Turkey, and constantly complained to his superiors about being sent to the latter place.[5] It during his time in Turkey when Henderson played a major role in the negotiations about the Mosul dispute as Turkish president Mustafa Kemal had laid claim to the Mosul region of Iraq.[5] Henderson was prepared to yield about Turkish demands for Constantinople, arguing that after the Chanak crisis of 1922, when it was dramatically revealed that public opinion in both Britain and the Dominions were unwilling go to war over the issue that Britain had a very weak hand, but was more forceful in upholding the British claim to the Mosul region.[5]

He served as an envoy to France in 1928/29 and as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia between 1929 and 1935,[6] where he was in close confidence with King Alexander and Prince Paul. Henderson had been lobbying for a major post in the embassy in Paris and did not want to the minister in Belgrade, notably continuing to pay the rent for his apartment in Paris for some time after moving to Belgrade as he was had expecting to move back to Paris soon.[7] The British legation in Belgrade was considered to be unglamorous post in contrast to the "grand embassies" in Paris, Berlin, Rome, Moscow, Vienna, Madrid and Washington. During his time in Belgrade, Henderson became a very close friend of King Alexander, as Henderson had a strong tendency towards hero-worship and in King Alexander he found a hero worthy of his admiration.[7] Henderson's dispatches from Belgrade took on a notably pro-Yugoslav tone as for Henderson King Alexander was a hero who could do no wrong.[8] In January 1929, King Alexander, who until then had been a constitutional monarch, had staged a "self-coup", abolishing democracy and making himself the dictator of Yugoslavia. Henderson's friendship with King Alexander, who shared his love of hunting and guns, notably increased British influence in Yugoslavia, which first brought him attention in the Foreign Office.[7]

As during his time in Berlin, Henderson took exception to any negative remark in the British press about Yugoslavia, writing to the Foreign Office if anything could be done to silence criticism of Yugoslavia.[7] After attending King Alexander's funeral, Henderson wrote: "I felt more emotion at King Alexander's funeral than I felt at any other except my mother's".[7] Henderson wrote to a friend in Britain in 1935: "My sixth winter in the Belgrade trenches is the worse of all. The zest has gone out of it with King Alexander gone. It interested me enormously to play Stockmar to his Albert and that made all the difference".[7] In January 1935, the Permanent Undersecretary at the Foreign Office, Sir Robert "Van" Vansittart sharply rebuked Henderson for a letter he had written to Crown Prince Paul, the Regent of Yugoslavia, for the boy king Peter II, in which Henderson strongly supported Yugoslavia's complaints against Italy.[8] Vansittart complained particularly about Henderson's claim that the Italian government was supporting Croat and Macedonian separatist terrorists and that Italy had been involved in the assassination of King Alexander in Marseilles in October 1934, writing "Are we convinced of this and do we wish Prince Paul to think that we are convinced of it".[8]

In 1935 he became Ambassador to Argentina before on 28 May 1937 the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, appointed him Ambassador in Berlin. A subsequent Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, wrote:

Why he did so is difficult to understand ….... Henderson proved a complete disaster; hysterical, self-opinionated and unreliable. Eden later realised what a terrible mistake he had made.[9]

Eden wanted an ambassador in Berlin who could get along well with dictators, and Vansittart gave him a list of three diplomats who had shown a strong partiality towards autocratic leaders, namely Henderson, Sir Percy Loraine and Sir Miles Lampson.[10] In his 1956 memoirs The Mist Procession, Vansittart wrote about the appointment of Henderson: "Nevile Henderson...made such a hit with the dictator [King Alexander] by his skill at shooting that he was ultimately picked for Berlin. All know the consequences".[11] Henderson's promotion from being the ambassador in Buenos Aires to being the ambassador in Berlin-regarded as one of the "grand embassies" in the Foreign Office-was a major boost to his ego.[12] Henderson wrote at the time that he believed he had been "specially selected by Providence for the definite mission of I trusted, helping to preserve the peace of the world".[10] As he crossed the Atlantic on a ship to take him back to Britain, Henderson who was fluent in German, read Mein Kampf in the original German version to acquaint himself with the thinking of Adolf Hitler..[12] Henderson wrote in his 1940 The Failure of a Mission that he was determined "to see the good side of the Nazi regime as well as the bad, and to explain as objectively as I could its aspirations and viewpoint to His Majesty's Government".[13]

Upon arriving in London, Henderson met the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Neville Chamberlain, who was due to replace Stanley Baldwin as prime minister the next month, for a briefing about the Berlin mission.[14] Some controversy has ensued over just what precisely Chamberlain told Henderson.[14] In his book Failure of a Mission, Henderson wrote that Chamberlain "outlined to me his views on the general policy towards Germany and I think I may honestly say to the last and bitter end I followed the general line which he set me, all the easily and faithfully since it corresponded so closely with my own private conception of the service I could best render in Germany to my own country".[12] Henderson was to claim that Chamberlain had authorised him to commit "calculated indiscretions" in the pursuit of peace, through the German-born American historian Abraham Ascher no evidence has emerged to support this claim.[11] T.Philip Conwell-Evans, a pro-Nazi British historian who taught German history at Königsburg University, was later to claim that Henderson had told him that Chamberlain had made him his personal envoy to Germany and he was to by-pass Vansittart by taking orders directly from the Prime Minister's office.[14] Regardless of what Chamberlain said to Henderson in April 1937, Henderson always seemed to have regarded himself as directly answerable to 10 Downing Street and showed a marked tendency to ignore Vansittart.[15]

A believer in appeasement policies, Henderson thought Adolf Hitler could be controlled and pushed toward peace and cooperation with the Western powers. Like almost all of the British elite in the interwar era, Henderson believed that the Treaty of Versailles was far too harsh on Germany, and if only the terms of Versailles were revised in Germany's favor, then another world war could be prevented.[16] Neville wrote the charge that Henderson was pro-Nazi is incorrect as Henderson was rather anti-Versailles as he had been advocating revising the terms of the Treaty of Versailles in favor of Germany long before Hitler ever came to power.[16] By contrast, Ascher credited Henderson's beliefs about avoiding war due to his belief to uphold white supremacy and to avoid another "fratricidal" war between white peoples at a time when Asian, black and brown peoples were starting to demand equality, citing Henderson's dispatch to Eden on 26 January 1938 that warned that another Anglo-German war: "would be...absolutely disastrous-I cannot imagine and would be unwilling to survive the defeat of the British Empire. At the same time, I would view with dismay another defeat of Germany, which would merely serve the purposes of inferior races".[17]

Shortly after arriving in Berlin, Henderson started to clash with Vansittart. Vansittart complained that Henderson was exceeding his brief and becoming too close to the Nazi leaders, especially Hermann Göring who became Henderson's best friend.[16] The same tendency towards hero-worship that Henderson had displayed towards King Alexander when he was in Belgrade reasserted itself in Berlin towards Göring as Henderson had a fascination with militaristic authority figures.[7] Göring shared Henderson's love of hunting and guns, and the two frequently went off together on hunting trips in the forests of Germany.[4] In June 1937, the Prime Minister of Canada, William Lyon Mackenzie King, visited Berlin to meet Hitler and during the same visit, Mackenzie King told Henderson that Hitler had said "they all liked him and felt he had a good understanding of German problems", a remark that appealed much to Henderson's vanity.[13] Hitler called Henderson "the man with the carnation" (a reference to the red carnation Henderson always wore) and despised him, finding Henderson to be too superior in his manners for his liking.[18] In contrast to his close friendship with Göring, Henderson's relationship with the Foreign Minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, was extremely antagonistic as Henderson detested Ribbentrop, writing to King George IV that Ribbentrop was "eaten up with conceit".[18]

When Henderson accepted Göring's invitation to attend the 1937 Nazi Party Rally in Nuremberg without consulting the Foreign Office, Vansittart was furious, writing that it was "extraordinary" that Henderson should "not only take an important decision like this off his own bat without giving us a chance at consultation...but also announce it to a foreign colleague as a decision".[16] Vansittart wrote to Henderson that he should not attend the Party Rally in Nuremberg, saying "you would be suspected of giving countenance or indeed eulogy (as alleged by one Member of Parliament) to the Nazi system" and the Foreign Office would be accused of having "fascist leanings".[19] Henderson wrote back that "one has to be empirical to a certain degree and since Nazism could not be wished away, what was the point of being discourteous to Hitler and unnecessarily irritating to him?"[19] Much to Vansittart's annoyance, Henderson attended the Nazi Party Rally in Nuremberg in September 1937, which was widely taken at the time as British approval of National Socialist ideology.[16]

Henderson called the Party Rally of 1937, which took place between 10-11 September, a most impressive event attended by some 140, 000 Germans, who were most enthusiastic for the regime.[19] Henderson wrote that his hosts in Nuremberg went out of their way to be friendly towards him, giving him a luxurious apartment to stay in and inviting him to sumptuous meals with the best German food and wine being served.[19] From Nuremberg, Henderson reported to London that:

"We are witnessing in Germany the rebirth, the reorganisation and unification of the German nation. One may criticise and disapprove, one may thoroughly dislike the threatened consummation and be apprehensive of its potentialities. But let us make no mistake. A machine is being built up in Germany, which in the course of this generation, if it succeeds unchecked, as there is no reason to believe that it will not, will be extraordinarily formidable. All this was achieved in less than five years. Germany is now so strong it can no longer be attacked with impunity, and soon, the country will be prepared for aggressive action".[19]

However, Henderson saw no reason for alarm, writing that "we are perhaps entering the quieter phrase of Nazism, of which the first indication has been the greater tranquility of the 1937 meeting [at Nuremberg]."[19] Henderson spoke with Hitler at Nuremberg, and described him as seeking "reasonableness" in foreign affairs with a special interest in reaching an "Anglo-German understanding".[19]

On 16 March 1938 Henderson wrote to the Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, his view that "British interests and the standard of morality can only be combined if we insist upon the fullest possible equality for the Sudeten minority of Czechoslovakia".[20] Unlike Basil Newton, the British minister in Prague, Henderson was initially advocated plans to turn Czechoslovakia into a federation, writing to Lord Halifax "how to secure, if we can, the integrity of Czechoslovakia".[21] At a meeting with Vojtech Mastny, the Czechoslovak minister in Berlin, on 30 March 1938, Henderson admitted that Czechoslovakia had the best record for the treatment of its minorities in Eastern Europe, but criticised Czechoslovakia for being an unitary state, which he argued caused too many problems in a state made up of Czechs, Slovaks, Magyars, Germans, Poles and Ukrainians.[22] Henderson told Mastny that he felt becoming a "Federal State" was Czechoslovakia's best hope and wanted Czechoslovakia to reorient its foreign policy upon "Prague-Berlin-Paris axis" instead of the existing "Prague-Paris-Moscow axis".[23]

In the spring of 1938, Henderson formed an alliance with Newton to work together to persuade decision-makers in London to side with Germany against Czechoslovakia.[24] When Henderson sent Newton a private letter praising him for his pro-German dispatches on 19 May 1938, the latter replied with a letter saying he hoped Henderson would "be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize and when that is done, I hope I may receive honorable mention. You have much the hardest job".[24]

During the May Crisis of 20-21 May 1938, Henderson was badly shaken by the partial Czechoslovak mobilisation, which for him proved that President Edvard Beneš was a dangerous and reckless man.[23] At the same time, Henderson formed alliances with Baron Ernst von Weizsäcker, the State Secretary of the Auswärtiges Amt; André François-Poncet, the French ambassador in Berlin and Baron Bernardo Attolico, the Italian ambassador in Berlin; to work together to peacfully "manage" Germany's return to great power status.[25] Acting independently of their own national governments, Weizsäcker, Attolico, Henderson and François-Poncet all worked together in a common front on one hand to sabotage the plans of Hitler and Ribbentrop to attack Czechoslovakia while at same time working to ensure the Sudetenland, the ostensible object of the German-Czechoslovak dispute, be handed over to Germany.[25] Attolico, Weizsäcker, , Henderson and François-Poncet would meet in secret to discuss in French to share information and to devise strategies for stopping a war in 1938.[25] Weizsäcker and Henderson both wanted a "chemical dissolution of Czechoslovakia" instead of the "mechanical dissolution" (i.e war) favored by Hitler and Ribbentrop.[25] After Göring, Weizsäcker was the German official Henderson was most close to during his time in Berlin.

Despite his earlier pro-Yugoslav views, Henderson during his time in Berlin started to display strong anti-Slavic views, writing to the Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax on 22 August 1938: "The Teuton and the Slav are irreconcilable-just as are the Briton and the Slav. Mackenzie King told me last year after the Imperial Conference that the Slavs in Canada never assimilated with the people and never became good citizens".[26] As the crisis over the Sudetenland region intensified in September 1938, Henderson became convinced that Britain should not fight a major war with Germany, which jeopardised the British Empire, over the Sudetenland, all the more so as he believed that it was it "unjust" for the Treaty of Versailles to have assigned the Sudetenland to Czechoslovakia in the first place..[27] In September 1938, Henderson along with Lord Halifax and Sir Horace Wilson, the Chief Industrial Adviser to the government, were the only ones aware of Chamberlain's "Plan Z" to have the Prime Minister fly to Germany to meet Hitler personally and find out just exactly it was that he wanted with the Sudetenland.[27]

After Hitler gave his keynote speech at the 1938 Nuremberg Party Rally on 12 September 1938 demanding that President Beneš either allow the Sudetenland to join Germany or else he would invade Czechoslovakia, Henderson who attended the Nuremberg rally reported to London that Hitler "driven by the megalomania inspired by the military force which he has built up...he may have crossed the borderline into insanity".[28] In the same dispatch, Henderson wrote he could not speak with "certitude" over what Germany might do as "everything depends on the psychology of one abnormal individual".[28] Henderson spoke with Hitler after he gave his speech at the Party Rally, and reported that Hitler "even while addressing the Hitler Youth" was so nervous that he could not relax, leading to Henderson to conclude: "His abnormality seemed to me even greater than ever".[28] Despite Henderson's belief that Hitler might have actually gone mad, he still found much to admire about Der Führer, writing he had "sublime faith in his own mission and that of Germany in the world" and "he is a constructive genius, a builder and no mere demagogue".[28] Henderson did not believe that Hitler wanted all of Czechoslovakia, writing to Lord Halifax that all Hitler wanted was to secure "fair and honorable treatment for the Austro- and Sudeten Germans" even at the price of war, but Hitler "hates war as much as anyone".[28]

Henderson was ambassador at the time of the 1938 Munich Agreement, and counselled Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain to enter into it. Shortly thereafter, he returned to London for medical treatment, returning to Berlin in ill-health in February 1939 (he would die of cancer less than four years later).[29] In October 1938, Henderson was diagnosed with cancer, causing him to leave for London.[17] During the interval between October 1938-February 1939, the British Embassy in Berlin was run the charge d'affairs, Sir George Ogilvie-Forbes, a member of the Scottish gentry and a protege of Vansittart.[17] During this period, the dispatches from Berlin changed markedly as Ogilvie-Forbes stated his belief that Hitler's aims went beyond revising the Treaty of Versailles towards winning Germany "world power status".[30] Ogilvie-Forbes wrote to London 6 December 1938 that based on the information he was receiving that he believed Hitler would start a war sometime in 1939 with Der Führer only divided about whatever it would be in western Europe or eastern Europe.[30] Unlike Henderson, who tended to gloss over the sufferings of the German Jewish community, Ogilvie-Forbes gave far more attention to Nazi antisemitism.[31] Ascher, himself a German Jew, noted in Ogilvie-Forbes's dispatches to London that there was a real sense of personal empathy with the sufferings of German Jews, which Henderson never displayed.[31] After Hitler gave his "Prophecy Speech" to the Reichstag on 30 January 1939, Ogilvie-Forbes predicated that the "extermination" of Jews in Germany "can only be a matter of time".[31]

When Henderson returned to Berlin on 13 February 1939, his first action was to call a meeting of the senior staff of the British Embassy, where he castigated Ogilvie-Forbes for his negative tone in his dispatches during his absence and announced that henceforward all dispatches to London would have to conform to his views, and that any diplomat who reported otherwise would be fired from the Foreign Office.[32] On 18 February 1939, Henderson reported to London: "Herr Hitler does not contemplate any adventures at the moment...all stories and rumors to the contrary are completely without foundation".[33] In February 1939, Henderson cabled the FCO in London:

If we handle him (Hitler) right, my belief is that he will become gradually more pacific. But if we treat him as a pariah or mad dog we shall turn him finally and irrevocably into one.[34]

On 6 March 1939, Henderson sent a lengthy dispatch to Lord Halifax attacking almost everything everything Ogilvie-Forbes had written during his time when he was in charge of the British Embassy.[33] Besides for disallowing Ogilvie-Forbes, Henderson also attacked British newspapers for negative coverage of Nazi Germany, especially the Kristallnacht pogrom, and demanded that the Chamberlain government impose censorship to end all negative coverage of the Third Reich.[33] Henderson wrote: "If a free press is allowed to run riot without guidance from higher authority, the damage which it may do is unlimited. Even war may be one of its consequences".[33] Henderson praised Hitler for his "sentimentality" and wrote "the humiliation of the Czechs [at the Munich conference] was a tragedy", but it was Beneš's own fault for failing to give the Sudeten Germans autonomy when he had the chance.[33] Henderson called Kristallnacht a "disgusting exhibition" which was however "comprehensible within limits. The German authorities were undoubtedly seriously alarmed lest another Jew, emboldened by the success of Grynszpan should follow his example and murder either Hitler or one of themselves".[35]

After Wehrmacht troops on 15/16 March 1939 occupied the remaining territory of the Czechoslovak Republic in defiance of the Agreement, Chamberlain spoke of a betrayal of confidence and decided to withstand German aggression. Henderson handed over a protest note and was intermittently recalled to London. Henderson wrote that "Nazism has crossed the Rubicon of the purity of race" by creating the Protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia and the seizure of the "Czech lands" of Bohemia and Moravia "cannot be justified on any grounds".[36] By late March 1939, there was a feeling within the cabinet that Henderson could no longer effectively represent Britain in Berlin, but Henderson was kept on for the want of a suitable "grand embassy" to send him to as a replacement.[37] There was talk of sending Henderson to Washington; however there were objections that Henderson's tendency to commit "calculated indiscretions" would not mix well with the American press, who were inclined to report any indiscretions by public figures, calculated or not.[37] The State Department made it clear to the Foreign Office that they felt that Henderson would be an embarrassment in Washington.[37] When Henderson asked for leave to visit Canada in the spring of 1939, he was told that he would have to give the Foreign Office copies beforehand of any lectures he planned to give as by this point no-one in the Chamberlain government trusted Henderson to "speak sensibly" about Germany.[37]

On 29 April 1939, the French ambassador in Berlin, Robert Coulondre reported to Paris that when Germany occupied the Czech part of Czecho-Slovakia on 15 March 1939, that Henderson, "always an admirer of the National Socialist regime, careful to protect Mr. Hitler's prestige, was convinced that Great Britain and Germany could divide the world between them" was very angry when he learned that the Reich had just violated the Munich Agreement as it "wounded him in his pride".[38] Coulondre went on to write: "Yesterday, I found him exactly as I knew him in February".[38] Coulondre added that Henderson had told him that the German demand that the Free City of Danzig be allowed to rejoin Germany was justified in his view and the introduction of conscription in Britain did not mean that British policies towards Germany were changing.[38] Coulondre concluded "it appears that events barely touched Sir Nevile Henderson, like water over a mirror...It would seem that he forgot everything and failed to learn anything".[38] Henderson's relations were Coulondre were unfriendly and cold as Coulondre distrusted both him and Weizsäcker, and unlike François-Poncet, he refused to join the "group of four" that had met in 1938 to stop a war.[25] By early May 1939, Henderson was reporting to London that Hitler still wanted good relations with Britain, but only if the British would end "the policy of encirclement".[36] Henderson further added that he believed in the "justice" of Hitler's demand that the Free City of Danzig rejoin Germany, writing that Danzig was "practically a wholly German city", and that Hitler did not want a war with Poland, through one might break out "if his offer to Poland was uncompromisingly rejected".[37]

During the Danzig crisis, Henderson consistently took the line that Germany was justified in demanding the return of the Free City of Danzig and that the onus was on the Poles to make concessions to Germany by allowing the Free City to "go home to the Reich".[39] Henderson wrote to Lord Halifax about Danzig and the Polish Corridor: "Can we allow the Polish government to be too uncompromising with them?"[40] Henderson felt that the Treaty of Versailles had been unjust towards Germany by creating the Free City of Danzig and giving the Polish Corridor and part of Silesia to Poland, and his preferred solution to the crisis was to have Britain pressure the Poles into concessions.[40] However, Henderson did believe that Britain needed to deter Germany from attacking Poland while Britain pressured the Poles into concessions, and for this reason he favored the "peace front" as the best form of deterrence.[40] Despite his distrust of the Soviet Union, he did support having the Soviet Union join the "peace front" as the best way of deterring Germany from invading Poland.[40]

On the eve of the Second World War, Henderson came into frequent conflict with Sir Alexander Cadogan, Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. Henderson argued that Britain should go about rearmament in secret, as a public rearmament would encourage the belief that Britain planned to go to war with Germany. Cadogan and the Foreign Office disagreed.

With the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact on 23 August 1939 and the Anglo-Polish military alliance two days later, war became imminent. On the night of 30 August, Ambassador Henderson had an extremely tense meeting with German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. Ribbentrop presented the German "final offer" to Poland at midnight, and warned Henderson that if he received no reply by dawn, the "final offer" would be considered rejected. The American historian Gerhard Weinberg described the scene: "When Ribbentrop refused to give a copy of the German demands to the British Ambassador at midnight of 30–31 August 1939, the two almost came to blows. Ambassador Henderson, who had long advocated concessions to Germany, recognised that here was a deliberately conceived alibi the German government had prepared for a war it was determined to start. No wonder Henderson was angry; von Ribbentrop on the other hand could see war ahead and went home beaming."[41]

While negotiating with the Polish ambassador Józef Lipski and advising accommodation over Germany's territorial ambitions – as he had during the Austrian Anschluss and the occupation of Czechoslovakia – the Nazis staged the Gleiwitz incident and the Invasion of Poland began on 1 September. It was Henderson who had to deliver Britain's final ultimatum on the morning of 3 September 1939 to Minister Ribbentrop, stating that if hostilities between Germany and Poland did not cease by 11 a.m. that day, a state of war would exist. Germany did not respond, and Prime Minister Chamberlain declared war at 11:15 a.m. Henderson and his staff were briefly interned by the Gestapo before finally returning to Britain on 7 September.

_diplomat_memorial.jpg)

After returning to London, Henderson asked for another ambassadorship, but was denied. He wrote Failure of a Mission: Berlin 1937–1939, which was published in 1940, in which he spoke highly of some members of the Nazi regime, including Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, but not von Ribbentrop. He had been on friendly terms with members of the Astors' Cliveden set, which also supported appeasement. Henderson wrote in his memoirs how eager Prince Paul had been to illustrate his military plans to counter Mussolini's projected assault on Dalmatia, when the main body of the Italian Royal Army had been sent overseas.[42] The historian A. L. Rowse described Failure of a Mission as "an appalling revelation of fatuity in high place".[43]

Death

He died on 30 December 1942 from cancer which he had been suffering from since 1938. He was staying at the Dorchester Hotel in London at the time. He never married.[44] Informed by his doctors that he had around six months left to live, he wrote an anecdote-filled diplomatic memoir, Water Under the Bridges, posthumously published in 1945. Its final chapter defends his work in Berlin and the policy of "appeasement," praises the late Prime Minister Chamberlain for being "an honest and brave man," and argues on behalf of the Munich Agreement on the grounds that Britain was too weak militarily in 1938 to have stood up to Hitler; it also argues that if Germany had invaded Czechoslovakia, that nation would have fallen in, at most, a few months.[45]

References

- ↑ Appeasing Hitler: The Diplomacy of Sir Nevile Henderson, 1937–39, Peter Neville, Palgrave Macmillan, 1999, ISBN 978-0333739877 p. 1.

- ↑ Sir Nevile Henderson, Water Under the Bridges, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1945, p. 10. https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.524087/2015.524087.Water-Under#page/n221/mode/2up

- 1 2 3 Neville 1999, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Neville 1999, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 Neville 1999, p. 9.

- ↑ "No. 33573". The London Gazette. 24 January 1930. p. 494.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Neville 1999, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 Neville 1999, p. 15.

- ↑ Macmillan, Harold (1966), Winds of Change 1914-1939, London: Macmillan, p. 530 citing Avon, The Earl of, The Eden Memoirs: Facing the Dictators, p. 504

- 1 2 Neville 1999, p. 22.

- 1 2 Ascher 2012, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 Neville 1999, p. 20.

- 1 2 Ascher 2012, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 Neville 1999, p. 20-21.

- ↑ Neville 1999, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Neville 2006, p. 149.

- 1 2 3 Ascher 2012, p. 74.

- 1 2 Neville 2006, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ascher 2012, p. 70.

- ↑ Neville 1999, p. 263.

- ↑ Neville 1999, p. 266.

- ↑ Neville 1999, p. 266-267.

- 1 2 Neville 1999, p. 267.

- 1 2 Neville 1999, p. 268.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Watt 2003, p. 334.

- ↑ Goldstein 1999, p. 282.

- 1 2 Neville 1999, p. 96.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ascher 2012, p. 73.

- ↑ Appeasing Hitler: The Diplomacy of Sir Nevile Henderson, 1937–39, findarticles.com; accessed 2 October 2014.

- 1 2 Ascher 2012, p. 74-75.

- 1 2 3 Ascher 2012, p. 76.

- ↑ Ascher 2012, p. 77-78.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ascher 2012, p. 78.

- ↑ Appeasing Hitler. The Diplomacy of Sir Nevile Henderson. 1937–39. Peter Neville. Palgrave 2000.

- ↑ Ascher 2012, p. 78-79.

- 1 2 Ascher 2012, p. 79.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ascher 2012, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 4 Duroselle 2004, p. 337.

- ↑ Neville 1999, p. 145-146.

- 1 2 3 4 Neville 1999, p. 146.

- ↑ A World At Arms by Gerhard Weinberg, p. 43.

- ↑ Jukic, Ilija, The Fall of Yugoslavia, New York and London, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Rowse, A. L. (1975) [1942]. A Cornish Childhood (Reprinted ed.). Cardinal. p. 109. ISBN 0351-18069-9.

- ↑ Peter Neville: ‘Henderson, Sir Nevile Meyrick (1882–1942)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011, accessed 1 Nov 2014

- ↑ Sir Nevile Henderson, Water Under the Bridges, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1945, p. 5; pp. 209-221. https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.524087/2015.524087.Water-Under#page/n221/mode/2up

Primary sources

- Henderson, Sir Neville (1940). Failure of a Mission 1937-9.

- Henderson, Sir Neville (1945). Water Under the Bridges.

- Henderson, Sir Neville (20 September 1939). "Final Report on the Circumstances Leading to the Termination of his Mission to Berlin". (Cmd 6115) Pamphlet.

- Secondary sources

- Ascher, Abraham (2012). Was Hitler a Riddle?: Western Democracies and National Socialism. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

- Duroselle, Jean-Baptiste (2004). France and the Nazi Threat: The Collapse of French Diplomacy 1932-1939. New York: Enigma.

- Gilbert, Martin (2014). The Second World War: A Complete History. RosettaBooks.

- Jukic, Ilija (1974). The Fall of Yugoslavia. New York and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- McDonogh, Frank (2010). Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the road to war. Manchester.

- Henderson, Sir Neville (25 March 1940). "War's First Memoirs". Life Magazine.

- Neville, Peter (1999). Appeasing Hitler The Diplomacy of Sir Nevile Henderson, 1937-39. London: Macmillan.

- Neville, Peter (2000). "Appeasing Hitler: The Diplomacy of Sir Nevile Henderson 1937–39". Studies in Diplomacy and International Relations. Palgrave.

- Neville, Peter (2006). Hitler and Appeasement: The British Attempt to Prevent the Second World War. London: Hambledon Continuum.

- Neville, Peter (2004). Henderson, Sir Nevile Meyrick (1882–1942). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online edn, Jan 2011 ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 1 Nov 2014.

- Watt, D.C. (2003), "Diplomacy and Diplomatists", in Maiolo, Joseph & Boyce, Robert, The Origins of World War Two: The Debate Continues, London: Macmillan, pp. 330–342, ISBN 0333945395

- Gerhard Weinberg (2005). A World At Arms: Global History of World War II. Cambridge.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nevile Henderson. |

- Failure of a Mission: Berlin 1937 – 1939

- Newspaper clippings about Nevile Henderson in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)

| Diplomatic posts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Howard William Kennard |

Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia 1929–1935 |

Succeeded by Ronald Ian Campbell |

| Preceded by Eric Phipps |

Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Ambassador to the Third Reich 1937–1939 |

Succeeded by No representation until 1950 Ivone Kirkpatrick |