Never Let Me Go (novel)

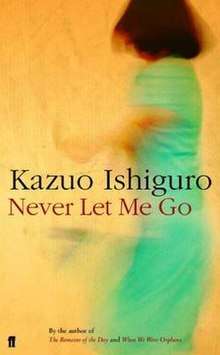

First-edition cover of the British publication | |

| Author | Kazuo Ishiguro |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Aaron Wilner |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Dystopian science fiction, speculative fiction |

| Publisher | Faber and Faber |

Publication date | 2005 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 288 |

| ISBN | 1-4000-4339-5 (first edition, hardback) |

| OCLC | 56058300 |

| 823/.914 22 | |

| LC Class | PR6059.S5 N48 2005 |

| Preceded by | When We Were Orphans |

| Followed by | Nocturnes |

Never Let Me Go is a 2005 dystopian science fiction novel by Nobel Prize-winning British author Kazuo Ishiguro. It was shortlisted for the 2005 Booker Prize (an award Ishiguro had previously won in 1989 for The Remains of the Day), for the 2006 Arthur C. Clarke Award and for the 2005 National Book Critics Circle Award. Time magazine named it the best novel of 2005 and included the novel in its TIME 100 Best English-language Novels from 1923 to 2005.[1] It also received an ALA Alex Award in 2006. A film adaptation directed by Mark Romanek was released in 2010; a Japanese television drama aired in 2016.[2]

Plot

Kathy is a student at Hailsham, a boarding school in England, where the teachers are known as guardians. They often tell their students about the importance of producing art and of being healthy (smoking is considered to be taboo, almost on the level of a crime, and working in the vegetable garden is compulsory). The students' art is then displayed in an exhibition, and the best art is chosen by a woman known to the students as Madame, who keeps their work in a gallery. Kathy develops a close friendship with two other students, Ruth and Tommy. Kathy develops a fondness for Tommy, looking after him when he is bullied and having private talks with him. However, Tommy and Ruth go steady.

In an isolated incident, Miss Lucy, one of the guardians, tells the students that they are clones who were created to donate organs to others, and after their donations they will die young. Miss Lucy is removed from the school as a result of her disclosure, but the students accept their fate.

Ruth, Tommy and Kathy move to the Cottages when they are 16 years old. They begin contact with the outside world. Ruth and Tommy are still together and Kathy has some sexual relationships with other men. Two older housemates, who had not been at Hailsham, tell Ruth that they have seen a "possible" for Ruth, an older woman who resembles Ruth and thus could be the woman from whom she was cloned. As a result, the five of them go on a trip to see her, but the two older students first want to discuss a rumour they have heard: that a couple can have their donations deferred if they can prove that they are truly in love. They believe that this privilege is for Hailsham students only and so wrongly expect that the others will know how to apply for it. They then find the possible, but the resemblance to Ruth is only superficial, causing Ruth to wonder angrily whether they were all cloned from "human trash".

During the trip, Kathy and Tommy separate from the others and look for a copy of a music tape that Kathy had lost when at Hailsham. Tommy's recollection of the tape and desire to find it for her make clear the depth of his feelings for Kathy. They find the tape, and then Tommy shares with Kathy a theory that the reason Madame collected their art was to determine which couples were truly in love, citing a teacher who had said that their art revealed their souls. After the trip, Kathy and Tommy do not tell Ruth of the found tape, nor of Tommy's theory about the deferral.

When Ruth finds out about the tape and Tommy's theory, she takes an opportunity to drive a wedge between Tommy and Kathy. Shortly afterwards she tells Kathy that, even if Ruth and Tommy were to split up, Tommy would never enter into a relationship with Kathy because of her sexual history. A few weeks later, Kathy applies to become a carer, meaning that she will not see Ruth or Tommy for about ten years.

After that, Ruth's first donation goes badly and her health deteriorates. Kathy becomes Ruth's carer, and both are aware that Ruth's next donation will probably be her last. Ruth suggests that she and Kathy take a trip and bring Tommy with them. During the trip, Ruth expresses regret for keeping Kathy and Tommy apart. Attempting to make amends, Ruth hands them Madame's address, urging them to seek a deferral. Shortly afterwards, Ruth makes her second donation and completes, an implied euphemism for dying.

Kathy becomes Tommy's carer and they go steady. Encouraged by Ruth's last wishes, they go to Madame's house to see if they can defer Tommy's fourth donation, bringing Tommy's artwork with him to support their claim that they are truly in love. They find Madame at her house, and also meet Miss Emily, their former headmistress, who lives with her. The two women reveal that guardians tried to give the clones a humane education, in contrast to other institutions. The gallery was a place meant to convey to the outside world that the clones are human beings. However, they can’t help Kathy and Tommy get a deferral, because such deferrals never existed.

Tommy knows that his next donation will end his life. Kathy resigns as Tommy's carer and does not see him again. She will soon start her own donations.

Title

The novel's title comes from a song on a cassette tape called Songs After Dark, by fictional singer Judy Bridgewater.[3] Kathy bought the tape during a swap meet-type event at Hailsham, which she often used to sing to and dance to the chorus: "Baby, never let me go." On one occasion, while dancing and singing, she notices Madame watching her and crying. Madame explains the encounter when they meet at the end of the book.

In another section of the book, Kathy refers to the three main characters "letting each other go" after leaving the cottages.

Characters

- Kathy – The protagonist and narrator of the novel. A clone raised to be a donor whose organs will later be harvested until she dies. During her childhood, Kathy is free-spirited, kind, loving, and stands up for what is right. At the end of the novel, Kathy is a young woman who doesn't show much emotion when looking back on her past. As an adult, she criticises people less and is accepting of the lives of her friends.

- Tommy – A male donor, and a friend of Kathy's. He is introduced as an uncreative and isolated young boy at Hailsham. He has a bad temper and is the object of many tricks played on him by the other children because of his short temper. Initially, he reacts by having bad temper tantrums, until Miss Lucy, a Hailsham guardian, tells him something that, for the short term, positively changes his life: it is okay if he’s not creative. He feels great relief. Years later, Miss Lucy tells him that she shouldn't have said what she did, and Tommy goes through another transformation. Once again upset by his lack of artistic skills, he becomes a quiet and sad teenager. As he matures, Tommy becomes a young man who is generally calm and thoughtful.

- Ruth – A female donor from Hailsham, described by Kathy as bossy. At the start of the novel, she is an extrovert with strong opinions and appears to be the center of social activity in her cohort; however, she is not as confident as the narrator initially perceived. She had hope for her future, but her hopes are crushed as she realises that she was born to be a donor and has no other future. At the Cottages, Ruth undergoes a transformation to become a more aware, thoughtful person who thinks about things in depth. She is constantly trying to fit in and be mature, repudiating things from her past if she perceives those things will negatively affect her image. She threw away her entire collection of art by fellow students, once her prized possessions, because she sensed that the older kids at The Cottages looked down on it. She becomes an adult who is deeply unhappy and regretful. Ruth eventually gives up on all of her hopes and dreams, and tries to help Kathy and Tommy have a better life.

- Madame (Marie-Claude) – A woman who visits Hailsham to pick up the children's artwork. Described as a mystery by the students at Hailsham. She acts professional and stern, and a young Kathy describes her as distant and forbidding. When the children decide to play a prank on her and swarm around her to see what she will do, they are shocked to discover that she seems disgusted by them. In a different circumstance, she silently watches Kathy dance to a song called "Never Let Me Go" and weeps at the sight. The two do not talk about it until years later; while Kathy interpreted the song's meaning as a woman who cannot have a baby, Madame wept at the thought of clones not being permitted to live long, happy and healthy lives as humans do.

- Miss Emily – Headmistress of Hailsham. Can be very sharp, according to Kathy. The children thought she had an extra sense in that allowed her to know where a child was if he or she was hiding.

- Miss Lucy – A teacher at Hailsham that the children feel comfortable with. She is one of the younger teachers at Hailsham, and tells the students very frankly that they exist only for organ donation. She feels a lot of stress while at Hailsham and is fired for what she tells the students.

- Chrissie – Another female donor, who is slightly older than the three main characters and was with them at the Cottages. She and her boyfriend, Rodney, were the ones who found Ruth's possible (i.e. the person from whom Ruth might have been cloned), and took Kathy, Tommy, and Ruth to Norfolk. She completes (i.e. dies because of her organ donations) before the book ends.

- Rodney – Chrissie's boyfriend, he was the one who originally saw Ruth's possible. He and Chrissie are mentioned to have broken up before she completed.

Reception

Critics disagree over the genre of the novel. Writing for The New Yorker, Louis Menand describes the novel as 'quasi-science-fiction', saying, 'even after the secrets have been revealed, there are still a lot of holes in the story [...] it's because, apparently, genetic science isn’t what the book is about.'[4] The New York Times book reviewer Sarah Kerr wondered why Ishiguro would write in, what she dubs, the 'pop genre—sci-fi thriller', claiming the novel to 'quietly upend [the genre's] banal conventions.'[5] Horror author Ramsey Campbell labelled it as one of the best horror novels since 2000, a 'classic instance of a story that's horrifying, precisely because the narrator doesn’t think it is.'[6]

Joseph O'Neill from The Atlantic suggested that the novel successfully fits into the coming of age genre. O'Neill wrote that 'Ishiguro's imagining of the children's misshapen little world is profoundly thoughtful, and their hesitant progression into knowledge of their plight is an extreme and heartbreaking version of the exodus of all children from the innocence in which the benevolent but fraudulent adult world conspires to place them.'[7] Theo Tait, in a review for The Telegraph, has a more general perspective of story: 'Gradually, it dawns on the reader that Never Let Me Go is a parable about mortality. The horribly indoctrinated voices of the Hailsham students who tell each other pathetic little stories to ward off the grisly truth about the future – they belong to us; we've been told that we're all going to die, but we've not really understood.'[8]

Adaptations

Mark Romanek directed a British film adaptation titled Never Let Me Go in 2010. In Japan, the Horipro agency produced a stage adaptation in 2014 called Watashi wo Hanasanaide (私を離さないで), and in 2016 under the same title TBS Television aired a television drama adaptation set in Japan starring Haruka Ayase and Haruma Miura.[9]

References

- ↑ "All Time 100 Novels". Time. 16 October 2005. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ "Never Let Me Go (Programme Site)". Never Let Me Go (Programme Site). TBS.co.jp. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ↑ Howell, Peter (2010-09-30). "A quest for the mystery pop singer of Never Let Me Go follows a winding path that leads to Bob Dylan, Atom Egoyan and Guy Maddin". The Toronto Star. ISSN 0319-0781. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ↑ Menand, Louis (28 March 2005). "Something About Kathy". New Yorker. New York. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ Kerr, Sarah (17 April 2005). "'Never Let Me Go': When They Were Orphans". New York Times. New York. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ "Ramsey Campbell interviewed by David McWilliam". Gothic Imagination at the University of Stirling, Scotland. 24 September 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ↑ O'Neill, Joseph (May 2005). "Never Let Me Go". The Atlantic. p. 123. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ Tait, Theo (13 March 2005). "A sinister harvest". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ "Never let Me Go Cast (in Japanese)". Never Let Me Go (Programme Site). TBS.co.jp. Retrieved 29 January 2016.