Neoprene

Neoprene (also polychloroprene or pc-rubber) is a family of synthetic rubbers that are produced by polymerization of chloroprene.[1] Neoprene exhibits good chemical stability and maintains flexibility over a wide temperature range. Neoprene is sold either as solid rubber or in latex form and is used in a wide variety of applications, such as laptop sleeves, orthopaedic braces (wrist, knee, etc.), electrical insulation, liquid and sheet applied elastomeric membranes or flashings, and automotive fan belts.[2]

Production

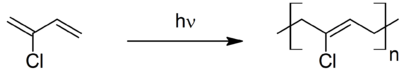

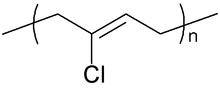

Neoprene is produced by free-radical polymerization of chloroprene. In commercial production, this polymer is prepared by free radical emulsion polymerization. Polymerization is initiated using potassium persulfate. Bifunctional nucleophiles, metal oxides (e.g. zinc oxide), and thioureas are used to crosslink individual polymer strands.[3]

History

Neoprene was invented by DuPont scientists on April 17, 1930 after Dr Elmer K. Bolton of DuPont attended a lecture by Fr Julius Arthur Nieuwland, a professor of chemistry at the University of Notre Dame. Nieuwland's research was focused on acetylene chemistry and during the course of his work he produced divinyl acetylene, a jelly that firms into an elastic compound similar to rubber when passed over sulfur dichloride. After DuPont purchased the patent rights from the university, Wallace Carothers of DuPont took over commercial development of Nieuwland's discovery in collaboration with Nieuwland himself. Arnold Collins at DuPont focused on monovinyl acetylene and allowed it to react with hydrogen chloride gas, manufacturing chloroprene.[4]

DuPont first marketed the compound in 1931 under the trade name DuPrene,[5] but its commercial possibilities were limited by the original manufacturing process, which left the product with a foul odor.[6] A new process was developed, which eliminated the odor-causing byproducts and halved production costs, and the company began selling the material to manufacturers of finished end-products.[6] To prevent shoddy manufacturers from harming the product's reputation, the trademark DuPrene was restricted to apply only to the material sold by DuPont.[6] Since the company itself did not manufacture any DuPrene-containing end products, the trademark was dropped in 1937 and replaced with a generic name, neoprene, in an attempt "to signify that the material is an ingredient, not a finished consumer product".[7] DuPont then worked extensively to generate demand for its product, implementing a marketing strategy that included publishing its own technical journal, which extensively publicized neoprene's uses as well as advertising other companies' neoprene-based products.[6] By 1939, sales of neoprene were generating profits over $300,000 for the company (equivalent to $5,277,990 in 2017).[6]

Applications

General

Neoprene resists degradation more than natural or synthetic rubber. This relative inertness makes it well suited for demanding applications such as gaskets, hoses, and corrosion-resistant coatings.[1] It can be used as a base for adhesives, noise isolation in power transformer installations, and as padding in external metal cases to protect the contents while allowing a snug fit. It resists burning better than exclusively hydrocarbon based rubbers,[8] resulting in its appearance in weather stripping for fire doors and in combat related attire such as gloves and face masks. Because of its tolerance of extreme conditions, neoprene is used to line landfills. Neoprene's burn point is around 260 °C (500 °F).[9]

In its native state, neoprene is a very pliable rubber-like material with insulating properties similar to rubber or other solid plastics.

Neoprene foam is used in many applications and is produced in either closed-cell or open-cell form. The closed-cell form is waterproof, less compressible and more expensive. The open-cell form can be breathable. It is manufactured by foaming the plastic with nitrogen gas, for the insulation properties of the tiny enclosed and separated gas bubbles (nitrogen is used for chemical convenience, not because it is superior to air as an insulator).

Civil engineering

Neoprene is used as a load bearing base, usually between two prefabricated reinforced concrete elements or steel plates as well to evenly guide force from one element to another.[10]

Aquatics

Neoprene is a popular material in making protective clothing for aquatic activities. Foamed neoprene is commonly used to make fly fishing waders and wetsuits, as it provides excellent insulation against cold. The foam is quite buoyant, and divers compensate for this by wearing weights. Thick wet suits made at the extreme end of their cold water protection are usually made of 7 mm thick neoprene. Since foam neoprene contains gas pockets, the material compresses under water pressure, getting thinner at greater depths; a 7 mm neoprene wet suit offers much less exposure protection under 100 feet of water than at the surface. A recent advance in neoprene for wet suits is the "super-flex" variety, which mixes spandex into the neoprene for greater flexibility.

Neoprene waders are usually about 5 mm thick, and in the medium price range as compared to cheaper materials such as nylon and more expensive waterproof fabrics made with breathable membranes.

Competitive swimming wetsuits are made of the most expanded foam; they have to be very flexible to allow the swimmer unrestricted movement. The downside is that they are quite fragile.

Home accessories

Recently, neoprene has become a favorite material for lifestyle and other home accessories including laptop sleeves, tablet holders, remote controls, mouse pads, and cycling chamois. In this market, it sometimes competes with LRPu (low-resilience polyurethane), which is a sturdier (more impact-resistant) but less-used material.

Music

The Rhodes piano used hammer tips made of neoprene in its electric pianos, after changing from felt hammers around 1970.[11]

Neoprene is also used for speaker cones and drum practice pads.

Hydroponic gardening

Hydroponic and aerated gardening systems make use of small neoprene inserts to hold plants in place while propagating cuttings or using net cups. Inserts are relatively small, ranging in size from 1.5 to 5 inches (4 to 13 cm). Neoprene is a good choice for supporting plants because of its flexibility and softness, allowing plants to be held securely in place without the chance of causing damage to the stem. Neoprene root covers also help block out light from entering the rooting chamber of hydroponic systems, allowing for better root growth and to help deter the growth of algae.

Automotive Industry

In automotive industry, neoprene is often used as a material for car seats or car seat covers[12]. Due to being wear-resistant and its protective characteristics, many car makers offer neoprene seats as an option for additional seat protection. Such seat covers are also included into vehicle packages for active drivers. Neoprene is based on a rubber layer for seat protection against moisture.

Other

Neoprene is used for Halloween masks and masks used for face protection, for insulating CPU sockets, to make waterproof automotive seat covers, in liquid and sheet-applied elastomeric roof membranes or flashings, and in a neoprene-spandex mixture for manufacture of wheelchair positioning harnesses. Because of its chemical resistance and overall durability, neoprene is sometimes used in the manufacture of dishwashing gloves, especially as an alternative to latex. In fashion, neoprene has been used by designers such as Gareth Pugh, Balenciaga, Rick Owens, Lanvin and Vera Wang. This trend, promoted by street style bloggers such as Jim Joquico of Fashion Chameleon,[13] gained traction and trickled down to mainstream fashion around 2014.

Precautions

Some people are allergic to neoprene while others can get dermatitis from thiourea residues left from its production. The most common accelerator in the vulcanization of polychloroprene is ethylene thiourea (ETU), which has been classified as reprotoxic. The European rubber industry project called SafeRubber focused on alternatives to the use of ETU.[14]

See also

References

- 1 2 Werner Obrecht, Jean-Pierre Lambert, Michael Happ, Christiane Oppenheimer-Stix, John Dunn and Ralf Krüger "Rubber, 4. Emulsion Rubbers" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2012, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.o23_o01

- ↑ "Technical information — Neoprene" (PDF). Du Pont Performance Elastomers. October 2003.

- ↑ Furman E. Glenn. "Chloroprene Polymers". Encyclopedia Of Polymer Science and Technology. doi:10.1002/0471440264.pst053.

- ↑ John K. Smith. The Ten-Year Invention: Neoprene and Du Pont Research, 1930–1939. Technology and Culture 26(1):34-55 January 1985

- ↑ "Neoprene : 1930 - Overview". DuPont Heritage. DuPont. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hounshell, David A.; Smith, John Kenly (1988). Science and Corporate Strategy : Du Pont R&D, 1902-1980 (Repr. ed.). Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press. pp. 253–257. ISBN 0-521-32767-9.

- ↑ "Neoprene : 1930 - In Depth". DuPont Heritage. DuPont. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ↑ "Neoprene - polychloroprene". DuPont Elastomers. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ↑ "3E Protect" (PDF). Msds.dupont.com. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ Damon Allen. Stiffness Evaluation of Neoprene Bearing Pads under Long-Term Loads. A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of The University Of Florida in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University Of Florida 2008

- ↑ "Steve's Corner - Hammer Tips". Fenderrhodes.com. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ "Seat Covers Materials". CARiD.com.

- ↑ "Neoprene: When fashion hijacked chemistry". Fashion Chameleon.

- ↑ "A Safer Alternative Replacement for Thiourea Based Accelerators in the Production Process of Chloroprene Rubber". cordis.europa.eu. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Neoprene. |