National Museum of Sudan

.jpg) Main entrance of the National Museum of Sudan | |

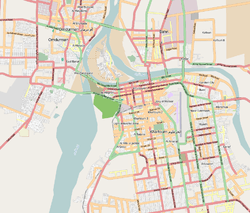

Location of the National Museum in Khartoum, Sudan | |

| Established | 1971 |

|---|---|

| Location |

El Neel Avenue, Khartoum, |

| Coordinates | 15°36′22″N 32°30′29″E / 15.606°N 32.508°E |

| Type | Archaeological collection of different epochs of Ancient Sudan and Ancient Egypt |

| Website | Sudan National Museum |

The National Museum of Sudan or Sudan National Museum, abbreviated SNM, is a double storied building constructed in 1955 and established as a museum in 1971. The building and its surrounding gardens house the largest and most comprehensive Nubian archaeological collection in the world including objects from the Paleolithic through to the Islamic period originating from every site of importance in the Sudan.[1]

In particular it houses collections of these periods of the History of Sudan: Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, A-Group culture, C-Group culture, Kerma Culture, Middle Kingdom of Egypt, New Kingdom of Egypt, Napata, Meroë, X-Group culture and medieval Makuria.

The museum is located on the El Neel (Nile) Avenue in Khartoum in Al-Mugran area near the spot where the White and the Blue Niles meet.[2]

Collection

The objects of the museum are displayed in four areas:

- The Main Hall on the ground floor

- The gallery on the first floor

- The Open Air Museum in the garden

- The Monumental Alley outside the museum building

The ground floor

Key highlights of the collections include:[3][4]

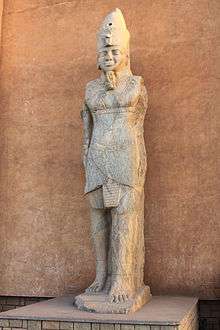

- The Taharqo statue. A 4-meter high granite statue of Pharaoh Taharqo, penultimate Pharaoh of the 25th dynasty, facing the main entrance welcomes the visitors of the museum. The statue was broken by the Egyptians upon sacking Napata in 591 BCE under the reign of Psamtik II, then buried in a pit by kushite priests and found by George Reisner in 1916.[5]

- Neolithic black-topped red burnished pottery and ram statuettes of the C-Group culture.

- Funerary artefacts and ceramic art.

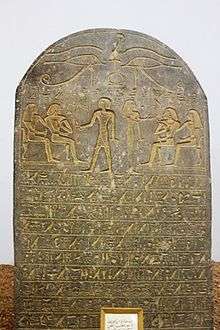

- Stela of the chief of Teh-khet Amenemhat, found at Debeira West

- Middle Kingdom of Egypt and New Kingdom of Egypt artefacts from the area of the third cataract like Sai, Soleb, Sedeinga and Kawa.

- A bowlegged figurine of the dwarf goddess Beset with a plump body and strange facial features: She has a large flat nose and a wide mouth framed by a lion mane and round lion ears. Uncommon in Egyptian art, Beset is pictured frontally and full-faced rather than in profile. She appears grasping an undulating snake in her 3-digit left hand indicating to control hostile forces. She is the protector of mothers and new-born children.[6]

- The Napata and Meroë periods of the Kingdom of Kush including the 25th dynasty: Funerary material, a granite statue of king Aspelta, the statue of an unknown Meroitic king represented as an archer and artefacts from its most representative sites like Meroe, Musawwarat es-Sufra and Naqa.

Kerma Culture jug with a beak in the shape of a hippopotamus head

Kerma Culture jug with a beak in the shape of a hippopotamus head Stela of the chief of Teh-khet, Amenemhat

Stela of the chief of Teh-khet, Amenemhat Female Demon Beset

Female Demon Beset- Bronze with gold statue of a Meroitic king as an archer

Beginning of CE sandstone-carved Meroitic statue raising its left arm

Beginning of CE sandstone-carved Meroitic statue raising its left arm

The first floor

- Wall paintings from the Christian Faras Cathedral dated between the 9th and the 13th century, detached during the UNESCO Salvage Campaign.

- The catalogue of Greek and Coptic inscriptions, produced primarily by the Christian culture of Nubia, was the scholarly contribution of Adam Lajtar from the Warsaw University in respect of Greek inscriptions and Jacques Van der Vliet of the Leiden University in respect of Coptic inscriptions. The inscriptions contain Nubian funerary epitaphs. The sites of these inscriptions are from Nubian territory in Sudan extending from Faras in the north to Soba in the south. The texts are inscribed on sandstone, marble or terracotta (36 inscriptions, mostly from Makuria ) plaques of generally rectangular shape.[7]

Fresco of Faras cathedral

Fresco of Faras cathedral The story from Daniel and of the three youths thrown into the furnace.

The story from Daniel and of the three youths thrown into the furnace.

The museum garden

The relocated temples from lake Nasser

In the museum garden are rebuilt some temples and tombs relocated from the submergence area of Lake Nasser. The Aswan High Dam built across the Nile River in Egypt created a reservoir in the Nubia area, which extended into Sudan's territory threatening to submerge the ancient temples. During the UNESCO Salvage Campaign [8] the following temples and tombs were re-erected in the museum garden according to the same orientation of their original location surrounding an artificial strip of water symbolic of the Nile:[9]

- Some remains of the temple of Ramses II of Aksha dedicated to Amun and to Ramses II himself. Preserved are a part of the Pylon with the Pharaoh worshipping the dynastic god Amun and some side-elements detailing submitted peoples.

- The temple of Hatshepsut of Buhen dedicated to Horus. The falcon-headed Horus, the mythical ancestor of all Pharaohs, and Hatshepsut appearing as a king, never as a woman.

- The temple of Kumma dedicated to the ram-headed Khnum, the god of the Nile cataracts.

- The tomb of the Nubian prince Djehuti-hotep at Debeira

- The temple of Semna dedicated to Dedwen and the deified Sesostris III. The sunk reliefs of this temple were carved over a large period hence the scenes are fragmented.

- The granite columns from the Faras Cathedral

Inscribed rocks

- Fragments of inscriptions of the submerged Nile-areas inserted onto fake rocks including a Nilometer with the name of queen Sobekneferu.

- At the banks of the water strip two Meroitic frog statues 60 cm in height from Basa representing the water-goddess Heket, as well as Beset the protector of pregnant women and newborn babies.

The Tabo colossi

Outside the museum building are set up two granite unfinished colossi from Tabo of the Argo Island. Due to missing inscriptions they cannot be assigned to any person but they have Roman influence.

The Monumental Alley

The lane leading from the museum car parking to the exhibition halls is flanked with meroitic statues of 2 rams and 6 dark sandstone men-eating lions. The lions are from the first century BCE, as shown by the two cartouches from king Amanikhabale engraved on the first lion on the right. As well as the frogs the lions were brought from Basa and represent the warlike lion-god Apedemak.

Meroitic frog

Maneating Lion

See also

References

- ↑ Sudan National Museum retrieved 7 March 2017

- ↑ Tripadvisor about the SNM retrieved 7 March 2017

- ↑ Museum guide retrieved 8 March 2017

- ↑ Maria Constanza de Simone, Nubia and Nubiens: The Museumization of a culture, University of Leiden,2014, pp.135-141

- ↑ Necia Desiree Harkless, Nubian Pharaos and Meroitic Kings. The Kingdom of Kush, 2006. ISBN 1-4259-4496-5

- ↑ Judith Weingarten: The Arrival of Bes[et] on Middle-Minoan Crete, in: There and Back Again – the Crossroads II. Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Prague. September 15–18, 2014. Edited by Jana Mynárová, Pavel Onderka and Peter Pavúk, pp.181-196. ISBN 978-80-7308-575-9

- ↑ Adam Lajtar; Sudan. Hay'ah al-Qawmiyah lil-Athar wa-al-Mata?if (2003). Catalogue of the Greek inscriptions in the Sudan National Museum at Khartoum (I. Khartoum Greek). Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-1252-6. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ↑ UNESCO Salvage Campaign retrieved 7 March 2017

- ↑ Friedrich Hinkel, Dismantling and Removal of Endangered Monuments in Sudanese Nubia, in: Kush V Journal of the Sudan Antiquity Service, 1965

.jpg)