National Archives Building, Jakarta

| National Archives Building | |

|---|---|

| Gedung Arsip Nasional | |

|

National Archives Building | |

location within Jakarta  National Archives Building, Jakarta (Indonesia) | |

| General information | |

| Status | Restored |

| Type | Museum |

| Architectural style | Old Indies style |

| Location | Jakarta, Indonesia |

| Address | Jalan Gajah Mada no. 111 |

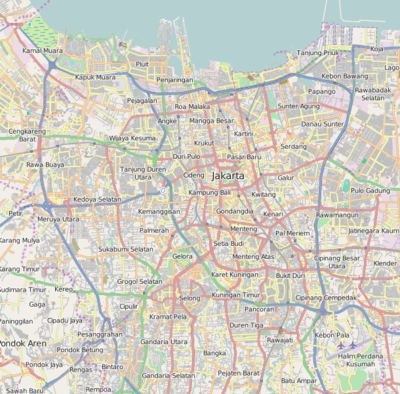

| Coordinates | 6°9′14″S 106°49′1″E / 6.15389°S 106.81694°ECoordinates: 6°9′14″S 106°49′1″E / 6.15389°S 106.81694°E |

| Groundbreaking | 1755[1] |

| Estimated completion | 1760[2] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | anonymous |

The National Archives Building (Indonesian: Gedung Arsip Nasional) is a museum in Jakarta, Indonesia. The building, formerly a late 18th-century private residence of Governor-General Reinier de Klerk, is part of the cultural heritage of Jakarta. The house is an archetypal Indies-Style house of the earliest period.

History

The history of the landhuis (Dutch "country house") of Reinier de Klerk on the west side of the Molenvliet began with the purchase of land in 1755 by de Klerk. De Klerk was appointed as a Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies in 1777.[2] He was not very pleased with this appointment, describing it as "serving the mustard after the meat has been eaten."

Unlike most government officials during the time, de Klerk had a reputation for being incorruptible, more so because he had no necessity for corruption as he was married to the very wealthy Sophia Francina Westpalm in Batavia. Sophia was the daughter of Michiel Westpalm and Gertruida Margaretha Goossens. Goossens was known for her beauty, and she married three times to rich husbands who all predeceased her. Sophia was heiress to the accumulated fortune, and thus de Klerk had the means to build a large country house.[3]

The original land he purchased extended towards the Krukut River to the west, the dike of the Molenvliet to the east, and Kampung Bali to the south. Construction of the house is presumed to have started as soon as the land was purchased.[1] De Klerk employed many people in the construction of his new estate, including non-Dutch and even non-Christians and also including slaves. At the time of de Klerk's death, the estate had two wings, a wash-house, a warehouse, slave quarters, a kitchen corner, stables and carriage houses, and a residence for the coachmen and the guards, as well as a rear building with many rooms. More than a hundred slaves worked and lived in the mansion; sixteen among them formed a band of musicians to entertain their master and guests at night.

The house was later inherited by Francois R. Radermacher, Sophia's son from her earlier marriage.[4]

Under the last will of Sophia in 1785, more than 50 slaves were emancipated and given some money to start their freedom. Other slaves bought their emancipation. The rest of the slaves, roughly a hundred, were auctioned off with their wives and children on January 28, 1786, in front of de Klerk's house. In the same year, Radermacher sold the property to another member of the Council of the Indies, Johannes Siberg.[4]

Siberg eventually became a Governor-General between 1801 and 1805, and stayed in the house during the French and English period (1808–1816). After Siberg's death in 1817, the house was auctioned off by his widow and bought by Lambert Zegers Veeckens in 1818.[1][4]

In 1819, Veeckens sold the house off again. The estate of Batavia was bought by Leendert Miero. Miero, born in 1755 in Grodka near Lemberg (now Lviv), arrived in Batavia in 1775 to work for the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was a Polish Jew whose real name was Jehoede Leip Jegiel Igel.[5] He hid his true identity because the Dutch East India Company prohibited Jews from travelling to its holdings, especially its new headquarters in Batavia. In 1777, Igel was received by de Klerk in the mansion and served as a low-ranking security guard for the mansion.[1][6] A story goes that, on a hot day, Igel fell asleep while guarding the entrance. When de Klerk unexpectedly returned, he was given 50 strokes for his laziness. On that same day, he swore that he would own the estate one day. After finishing his military service, Igel changed his name to Leendert Miero and worked as a goldsmith. Despite being illiterate, he was able to make a fortune and bought the estate of Pondok Gede. Miero was able to reveal his identity when the VOC agreed to include Jews in its ranks in 1782. Having finally bought the house, Miero invited big crowds to celebrate the anniversary of his lashing day for fifteen years, celebrated with a biblical humor.[1] Miero took two legal wives, but they bore him no children. Instead, he adopted four natural children born to him by four different slaves.[4]

Following the death of Miero on May 10, 1834,[4] the house continued to be inhabited by Leendert's heirs until it was sold again in 1844 to the College of Deacons of the Dutch Reformed Church. It was converted to an orphanage until 1900 and suffered many alterations, such as the addition of a Greek-style chapel in the front facade. In 1901, the colonial government acquired the building and made it the office of the Mining Department. The Greek-style chapel was demolished to restore the original facade of de Klerk's mansion.[4]

In 1925, major restoration took place. The pleasure garden was landscaped once more. The building was converted into the State Archive (Landsarchief) and remained an Archive Building following the independence of Indonesia.[4]

In 1974, the National Archives of Indonesia moved to Jalan Ampera Selatan in South Jakarta because the old building was deemed not appropriate for archives. After the transfer was completed in 1979, the house began to deteriorate. The paint peeled off and much of the ornamentation broke.[4]

In 1995, some Jakarta-based Dutch companies founded the Stichting Cadeau Indonesia (Indonesia Foundation prize) and collected money as a gift for the 50th anniversary of Indonesian Independence with the intention of restoring the mansion. During the visit of Queen Beatrix, a memorandum was signed in a reception held in the building. Despite the initial preparation, the National Archives of Indonesia made no realistic proposals, so, to prevent further damage, the restoration of the house started in 1997. With the highest standards, the restoration was made, including the restoration of the damaged drainage system that caused flooding around the mansion. On November 1, 1998, the restoration was completed.[4]

In the same year on May 13, during the restoration process, a nationwide riot broke out. A bank building next door to the National Archives Building was burned to the ground by the mobs, forcing the employees to seek shelter into the still-under-restoration National Archives Building. When the mobs followed them, about 80 workmen on site for the building's restoration chased them away.[7]

Building

The National Archive Building is an archetypal Dutch Indies country house of the 18th century. The style of its architecture is classified as the earliest form of the Indies Style, the Dutch Style (Nederlandse stijl). It was a period when Dutch-Style houses had not fully adapted to the tropical climate of the Dutch East Indies.

The National Archive Building is a two-storeyed house which almost exactly replicates its Dutch counterparts. The Dutch influence can be seen in the hipped roof, closed and solidly built facade, and high windows. The only concession to the tropical climate is the relatively large roof overhang compared with the original Dutch country houses.[8] Also, unlike their Dutch counterparts, the National Archive Building contains extensive ancillary quarters at the rear of the house to accommodate the large number of slaves which enabled the wealthy lifestyle of the residents.[8] It also had warehouses for the storage of goods acquired through private trading ventures.[8]

The interior of the National Archive Building is similar to a typical Dutch landhuis, but there are significant differences. The National Archive Building has taller ceilings and larger windows. It also has a brighter ambience, another consideration for the tropics.[8] The door is topped with wooden allegorical carvings.

A spacious pleasure garden surrounds the building. The original plot of the building was 27,000 m2, reduced to 9,000 m2. The rear garden contains a belfry.[9]

Collection

The building kept several historic VOC period items, among them 17th-century ebony furniture. The secretarybird, de Klerk’s coat of arms, is a recurring motif around the building.

The first floor exhibits a collection of maps dating from 1541. There are dining chairs and a dining table from the VOC period.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 de Haan 1922, pp. 72-6.

- 1 2 Akihary 1990, p. 11.

- ↑ Taylor 1983, p. 204.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Messakh 2008.

- ↑ Genealogie van de Familie Miero Meijer

- ↑ Miero, Leendert

- ↑ "A Shared Inheritance: Gedung Arsip Nasional". Kabar Indonesia. Kabar Media. January 4, 2009. Archived from the original on November 12, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Gill 1998, p. 110.

- ↑ Gemeentemuseum Helmond 1990, pp. 7-11.

Cited works

- Akihary, Huib (1990). Architectuur & Stedebouw in Indonesië 1870/1970. Zutphen: De Walburg Pers. ISBN 9072691024.

- de Haan, F. (1922). Oud Batavia - Eerste en tweede deel. Batavia: G. Kolff & Co.

- Gill, Ronald (1998). Gunawan Tjahjono, ed. Country Houses in the 18th Century. Indonesian Heritage - Architecture. 6. Singapore: Archipelago Press. ISBN 981-3018-30-5.

- Het Indische bouwen: architectuur en stedebouw in Indonesie : Dutch and Indisch architecture 1800-1950. Helmond: Gemeentemuseum Helmond. 1990. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- Messakh, Matheos V. (July 15, 2008). "A home truth about the house of a Dutch governor-general". The Jakarta Post. PT. Niskala Media Tenggara. Archived from the original on November 13, 2016. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (1983). The Social World of Batavia: European and Eurasian in Dutch Asia (illustrated ed.). Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299094706.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Archives of Indonesia. |