Napoleon complex

"Napoleon complex" is a theorised complex occurring in people of short stature. It is characterized by overly-aggressive or domineering social behaviour, and carries the implication that such behaviour is compensatory for the subject's stature. The term is also used more generally to describe people who are driven by a perceived handicap to overcompensate in other aspects of their lives. In psychology, the Napoleon complex is regarded as a derogatory social stereotype.[1]

Etymology

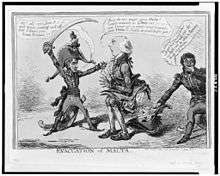

The Napoleon complex is named after Emperor Napoleon I of France. Common folklore supposes that Napoleon compensated for his lack of height by seeking power, war, and conquest. This view was fostered and encouraged by the British, who waged a propaganda campaign to diminish their enemy in print and art, during his life and after his death. In 1803 he was mocked in British newspapers as a short-tempered small man.[2] He was actually 5′4″ or 5′5″ tall, just an inch or two below the period's average adult male height.[3] Napoleon was often seen with his Imperial Guard, which contributed to the perception of his being short because the Imperial Guards were tall men. Other names for the purported condition include Napoleonic complex, Napoleon syndrome and Short man/person syndrome.[4][5][6][7]

Research

In 2007, research by the University of Central Lancashire suggested that the Napoleon complex (described in terms of the theory that shorter men are more aggressive to dominate those who are taller than they are) is likely to be a myth. The study discovered that short men were less likely to lose their temper than men of average height. The experiment involved subjects dueling each other with sticks, with one subject deliberately rapping the other's knuckles. Heart monitors revealed that the taller men were more likely to lose their tempers and hit back. University of Central Lancashire lecturer Mike Eslea commented that "when people see a short man being aggressive, they are likely to think it is due to his size, simply because that attribute is obvious and grabs their attention."[6]

The Wessex Growth Study is a community-based longitudinal study conducted in the UK that monitored the psychological development of children from school entry to adulthood. The study was controlled for potential effects of gender and socioeconomic status, and found that "no significant differences in personality functioning or aspects of daily living were found which could be attributable to height";[8] this functioning included generalizations associated with the Napoleon complex, such as risk-taking behaviours.[9]

Abraham Buunk, a professor at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, claimed to have found evidence of the small man syndrome. Researchers at the University found that men who were 1.63 metres (5 ft 4 in) were 50% more likely to show signs of jealousy than men who were 1.98 metres (6 ft 6 in).[4]

In 2018 evolutionary psychologist Mark van Vugt and his team at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam found evidence for the Napoleon complex in human males. Men of short stature behaved more (indirectly) aggressive in interactions with taller men.[10][11] Their evolutionary psychology hypothesis argues that in competitive situations when males, human or nonhuman, receive cues that they are physically outcompeted the Napoleon complex psychology kicks in: physically weaker males should adopt alternative behavioral strategies to level the playing field, including showing indirect aggression and coalition building.

See also

References

- ↑ Sandberg, David E.; Linda D. Voss (September 2002). "The psychosocial consequences of short stature: a review of the evidence" (PDF). Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. Elsevier Science Ltd. 16 (3): 450. doi:10.1053/beem.2002.0211. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ↑ "Greatest cartooning coup of all time: The Brit who convinced everyone Napoleon was short". National Post. 2016-04-28. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- ↑ David A. Bell, Napoleon: A Concise Biography (Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 18.

- 1 2 Fleming, Nic (13 March 2008). "Short man syndrome is not just a tall story". The Telegraph. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ↑ Morrison, Richard (2005-10-10). "Heart of the Fifties generation beats once again". The Times. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- 1 2 "Short men 'not more aggressive'". BBC News. 2007-03-28. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ↑ Owen Connelly (2006). Blundering to Glory: Napoleon's Military Campaigns. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 7.

- ↑ Ulph, F.; Betts, P; Mulligan, J; Stratford, R. J. (January 2004). "Personality functioning: the influence of stature". Archives of Disease in Childhood. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. 89 (1): 17–21. doi:10.1136/adc.2002.010694. PMC 1755926. PMID 14709494.

- ↑ Lipman, Terri H.; Linda D. Voss (May–June 2005). "Personality Functioning: The Influence of Stature". MCN: the American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 30 (3): 218. doi:10.1097/00005721-200505000-00019.

- ↑ Knapen, J. E., Blaker, N. M., & Van Vugt, M. (2018). The Napoleon Complex: When Shorter Men Take More. Psychological science, 0956797618772822. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618772822

- ↑ https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/naturally-selected/201405/does-putin-suffer-the-napoleon-complex