Nancy Drew

| Nancy Drew | |

|---|---|

|

1965 cover of the revised version of The Secret of the Old Clock, the first Nancy Drew mystery | |

| Created by | Edward Stratemeyer |

| Portrayed by | Bonita Granville, Pamela Sue Martin, Janet Louise Johnson, Tracy Ryan, Maggie Lawson, Emma Roberts and Sophia Lillis |

| Voiced by |

Lani Minella and Claire Boynton[1] |

| Information | |

| Gender | Female |

| Occupation | Detective |

| Family | Carson Drew (father) |

| Nationality | American |

Nancy Drew is a fictional character sleuth in an American mystery series created by publisher Edward Stratemeyer as the female counterpart to his Hardy Boys series. The character first appeared in 1930. The books are ghostwritten by a number of authors and published under the collective pseudonym Carolyn Keene.[2] Over the decades, the character evolved in response to changes in US culture and tastes. The books were extensively revised and shortened, beginning in 1959, in part to lower printing costs[3] with arguable success.[4][5] In the revision process, the heroine's original character was changed to be less unruly and violent.[6] In the 1980s, an older and more professional Nancy emerged in a new series, The Nancy Drew Files, that included romantic subplots for the sleuth.[7] The original Nancy Drew Mystery Stories series started in 1930, and ended in 2003. Launched in 2004, the Girl Detective series features Nancy driving a hybrid electric vehicle and using a cell phone. In 2012, the Girl Detective series ended, and a new current series called Nancy Drew Diaries was launched in 2013. Illustrations of the character evolved over time to reflect contemporary styles.[8] The character proves continuously popular worldwide: at least 80 million copies of the books have been sold,[9] and the books have been translated into over 45 languages. Nancy Drew is featured in five films, two television shows, and a number of popular computer games; she also appears in a variety of merchandise sold around the world.

A cultural icon, Nancy Drew is cited as a formative influence by a number of women, from Supreme Court Justices Sandra Day O'Connor[10] and Sonia Sotomayor to former Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton[11] and former First Lady Laura Bush.[12] Feminist literary critics have analyzed the character's enduring appeal, arguing variously that Nancy Drew is a mythic hero, an expression of wish fulfillment,[13] or an embodiment of contradictory ideas about femininity.[14]

The Nancy Drew character

Nancy Drew is a fictional amateur sleuth. In the original versions of the series, she is a 16-year-old high school graduate, and in later versions, is rewritten and aged to be an 18-year-old high school graduate and detective. In the series, she lives in the fictional town of River Heights[15] with her father, attorney Carson Drew, and their housekeeper, Hannah Gruen.[16] As a child (age ten in the original versions and age three in the later version), she loses her mother. Her loss is reflected in her early independence—running a household since the age of ten with a clear-cut servant in early series and deferring to the servant as a surrogate parent in later ones. As a teenager, she spends her time solving mysteries, some of which she stumbles upon and some of which begin as cases of her father's. Nancy is often assisted in solving mysteries by her two closest friends: cousins Bess Marvin and George Fayne. Bess is delicate and feminine, while George is a tomboy. Nancy is also occasionally joined by her boyfriend Ned Nickerson, a student at Emerson College.

Nancy is often described as a super girl. In the words of Bobbie Ann Mason, she is "as immaculate and self-possessed as a Miss America on tour. She is as cool as Mata Hari and as sweet as Betty Crocker."[17] Nancy is well-off, attractive, and amazingly talented:

At sixteen she 'had studied psychology in school, and was familiar with the power of suggestion and association.' Nancy was a fine painter, spoke French, and had frequently run motor boats. She was a skilled driver who at sixteen 'flashed into the garage with a skill born of long practice.' The prodigy was a sure shot, an excellent swimmer, skillful oarsman, expert seamstress, gourmet cook, and a fine bridge player. Nancy brilliantly played tennis and golf, and rode like a cowboy. Nancy danced like Ginger Rogers and could administer first aid like the Mayo brothers.[18]

Nancy never lacks money, and in later volumes of the series often travels to faraway locations, such as France in The Mystery of the 99 Steps (1966), Nairobi in The Spider Sapphire Mystery (1968), Austria in Captive Witness (1981), Japan in The Runaway Bride (1994), Costa Rica in Scarlet Macaw Scandal (2004), and Alaska in Curse of The Arctic Star (2013). Nancy is also able to travel freely about the United States, thanks in part to her car, which is a blue roadster in the original series and a blue convertible in the later books.[19] Despite the trouble and presumed expense to which she goes to solve mysteries, Nancy never accepts monetary compensation; however, by implication, her expenses are often paid by a client of her father's, as part of the costs of solving one of his cases.[20]

Creation of character

The character was conceived by Edward Stratemeyer, founder of the Stratemeyer Syndicate. Stratemeyer had created the Hardy Boys series in 1926 (although the first volumes were not published until 1927), which had been such a success that he decided on a similar series for girls, featuring an amateur girl detective as the heroine. While Stratemeyer believed that a woman's place was in the home,[21] he was aware that the Hardy Boys books were popular with girl readers and wished to capitalize on girls' interest in mysteries by offering a strong female heroine.[22]

Stratemeyer initially pitched the new series to Hardy Boys publishers Grosset & Dunlap as the "Stella Strong Stories", adding that "they might also be called 'Diana Drew Stories', 'Diana Dare Stories', 'Nan Nelson Stories', 'Nan Drew Stories', or 'Helen Hale Stories'."[23] Editors at Grosset & Dunlap preferred "Nan Drew" of these options, but decided to lengthen "Nan" to "Nancy".[24] Stratemeyer accordingly began writing plot outlines and hired Mildred Wirt, later Mildred Wirt Benson, to ghostwrite the first volumes in the series under the pseudonym Carolyn Keene.[25] Subsequent titles have been written by a number of different ghostwriters, all under the pseudonym Carolyn Keene.

The first four titles were published in 1930 and were an immediate success. Exact sales figures are not available for the years prior to 1979, but an indication of the books' popularity can be seen in a letter that Laura Harris, a Grosset and Dunlap editor, wrote to the Syndicate in 1931: "can you let us have the manuscript as soon as possible, and no later than July 10? There will only be three or four titles brought out then and the Nancy Drew is one of the most important."[26] The 6,000 copies that Macy's ordered for the 1933 Christmas season sold out within days.[27] In 1934 Fortune magazine featured the Syndicate in a cover story and singled Nancy Drew out for particular attention: "Nancy is the greatest phenomenon among all the fifty-centers. She is a best seller. How she crashed a Valhalla that had been rigidly restricted to the male of her species is a mystery even to her publishers."[28]

Evolution of character

The character of Nancy Drew has gone through many permutations over the years. The Nancy Drew Mystery series was revised beginning in 1959;[29] with commentators agreeing that Nancy's character changed significantly from the original Nancy of the books written in the 1930s and 1940s.[30] Commentators also often see a difference between the Nancy Drew of the original series, the Nancy of The Nancy Drew Files, and the Nancy of Girl Detective series.[31] Nevertheless, some commentators find no significant difference between the different permutations of Nancy Drew, finding Nancy to be simply a good role model for girls.[32] Despite revisions, "[w]hat hasn't changed, however, are [Nancy's] basic values, her goals, her humility, and her magical gift for having at least nine lives. For more than six decades, her essence has remained intact."[33] Nancy is a "teen detective queen" who "offers girl readers something more than action-packed adventure: she gives them something original. Convention has it that girls are passive, respectful, and emotional, but with the energy of a girl shot out of a cannon, Nancy bends conventions and acts out every girl's fantasies of power."[34]

Other commentators see Nancy as "a paradox—which may be why feminists can laud her as a formative 'girl power' icon and conservatives can love her well-scrubbed middle-class values."[35]

1930–1959: Early stories

The earliest Nancy Drew books were published as dark blue hardcovers with the titles stamped in orange lettering with dark blue outlines and no other images on the cover. They went through several changes in early years: leaving the orange lettering with no outline and adding an orange silhouette of Nancy peering through a magnifying glass; then changing to a lighter blue board with dark blue lettering and silhouette; then changing the position of the title and silhouette on the front with black lettering and a more "modern" silhouette. Nancy Drew is depicted as an independent-minded 16-year-old who has already completed her high school education (16 was the minimum age for graduation at the time); the series also occurs over time, as she is 18 by the early 1940s. Apparently affluent (her father is a successful lawyer), she maintains an active social, volunteer, and sleuthing schedule, as well as participating in athletics and the arts, but is never shown as working for a living or acquiring job skills. Nancy is affected neither by the Great Depression—although many of the characters in her early cases need assistance as they are poverty-stricken—nor by World War II. Nancy lives with her lawyer father, Carson Drew, and their housekeeper, Mrs. Hannah Gruen. Some critics prefer the Nancy of these volumes, largely written by Mildred Benson. Benson is credited with "[breathing] ... a feisty spirit into Nancy's character."[36] The original Nancy Drew is sometimes claimed "to be a lot like [Benson] herself – confident, competent, and totally independent, quite unlike the cardboard character that [Edward] Stratemeyer had outlined."[37]

This original Nancy is frequently outspoken and authoritative, so much so that Edward Stratemeyer told Benson that the character was "much too flip, and would never be well received."[38][39] The editors at Grosset & Dunlap disagreed,[40] but Benson also faced criticism from her next Stratemeyer Syndicate editor, Harriet Adams, who felt that Benson should make Nancy's character more "sympathetic, kind-hearted and lovable." Adams repeatedly asked Benson to, in Benson's words, "make the sleuth less bold ... 'Nancy said' became 'Nancy said sweetly,' 'she said kindly,' and the like, all designed to produce a less abrasive more caring type of character."[41] Many readers and commentators, however, admire Nancy's original outspoken character.[42]

A prominent critic of the Nancy Drew character, at least the Nancy of these early Nancy Drew stories,[43] is mystery writer Bobbie Ann Mason. Mason contends that Nancy owes her popularity largely to "the appeal of her high-class advantages."[44] Mason also criticizes the series for its racism and classism,[45] arguing that Nancy is the upper-class WASP defender of a "fading aristocracy, threatened by the restless lower classes."[46] Mason further contends that the "most appealing elements of these daredevil girl sleuth adventure books are (secretly) of this kind: tea and fancy cakes, romantic settings, food eaten in quaint places (never a Ho-Jo's), delicious pauses that refresh, old-fashioned picnics in the woods, precious jewels and heirlooms .... The word dainty is a subversive affirmation of a feminized universe."[47]

At bottom, says Mason, the character of Nancy Drew is that of a girl who is able to be "perfect" because she is "free, white, and sixteen"[17] and whose "stories seem to satisfy two standards – adventure and domesticity. But adventure is the superstructure, domesticity the bedrock."[47]

Others argue that "Nancy, despite her traditionally feminine attributes, such as good looks, a variety of clothes for all social occasions, and an awareness of good housekeeping, is often praised for her seemingly masculine traits ... she operates best independently, has the freedom and money to do as she pleases, and outside of a telephone call or two home, seems to live for solving mysteries rather than participating in family life."[48]

1959–1979: Revisions at Grosset & Dunlap

At the insistence of publishers Grosset & Dunlap, the Nancy Drew books were revised beginning in 1959, both to make the books more modern and to eliminate racist stereotypes.[49] Although Harriet Adams felt that these changes were unnecessary, she oversaw a complete overhaul of the series, as well as writing new volumes in keeping with the new guidelines laid down by Grosset & Dunlap.[3] The series did not so much eliminate racial stereotypes, however, as eliminate non-white characters altogether.[5] For example, in the original version of The Hidden Window Mystery (1956), Nancy visits friends in the south whose African-American servant, "lovable old Beulah ... serves squabs, sweet potatoes, corn pudding, piping hot biscuits, and strawberry shortcake."[50] The mistress of the house waits until Beulah has left the room and then says to Nancy, "I try to make things easier for Beulah but she insists on cooking and serving everything the old-fashioned way. I must confess, though, that I love it."[51] In the revised 1975 version, Beulah is changed to Anna, a "plump, smiling housekeeper".[52]

Many other changes were relatively minor. The new books were bound in yellow with color illustrations on the front covers. Nancy's age was raised from 16 to 18, her mother was said to have died when Nancy was three, rather than ten, and other small changes were made.[36] Housekeeper Hannah Gruen, sent off to the kitchen in early stories, became less a servant and more a mother surrogate.[53]

Critics saw this Nancy of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s as an improvement in some ways, a step back in others: "In these new editions, an array of elements had been modified ... and most of the more overt elements of racism had been excised. In an often overlooked alteration, however, the tomboyishness of the text's title character was also tamed."[54]

Nancy becomes much more respectful of male authority figures in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, leading some to claim that the revised Nancy simply becomes too agreeable, and less distinctive, writing of her, "In the revised books, Nancy is relentlessly upbeat, puts up with her father's increasingly protective tendencies, and, when asked if she goes to church in the 1969 The Clue of the Tapping Heels, replies, 'As often as I can' ... Nancy learns to hold her tongue; she doesn't sass the dumb cops like she used to."[55]

1980–2003: Continuing the Original series

Harriet Adams continued to oversee the series, after switching publishers to Simon & Schuster, until her death in 1982. After her death, Adams' protégés, Nancy Axelrad and Lilo Wuenn, and her three children, oversaw production of the Nancy Drew books and other Stratemeyer Syndicate series. In 1985, the five sold the Syndicate and all rights to Simon & Schuster. Simon & Schuster turned to book packager Mega-Books for new writers.[56] These books continued to have the characters solve mysteries in the present day, while still containing the same basic formula and style of the books during the Syndicate.

1986-1997: Files, Supermystery, and On Campus

In 1985, as the sale of the Stratemeyer Syndicate to Simon & Schuster was being finalized, Simon & Schuster wanted to launch a spin-off series, that focused on more mature mysteries, and incorporated romance into the stories. To test whether this would work, the final two novels before the sale, The Bluebeard Room and The Phantom of Venice, were used as backdoor pilots for the new series. The books read drastically different from the preceding novels of the past 55 years. For example, The Phantom of Venice (1985) opens with Nancy wondering in italics, "Am I or am I not in love with Ned Nickerson?"[57] Nancy begins dating other young men and acknowledges sexual desires: "'I saw [you kissing him] ... You don't have to apologize to me if some guy turns you on.' 'Gianni doesn't turn me on! ... Won't you please let me explain.'"[58] The next year, Simon & Schuster launched the first Nancy Drew spin-off, titled The Nancy Drew Files.

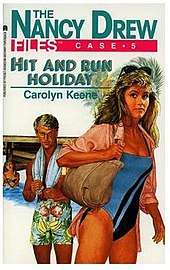

The Nancy Drew character of the Files series has earned mixed reviews among fans. Some contend that Nancy's character becomes "more like Mildred Wirt Benson's original heroine than any [version] since 1956."[59] Others criticize the series for its increasing incorporation of romance and "[dilution] of pre-feminist moxie."[60] One reviewer noticed "Millie [Mildred Wirt Benson] purists tend to look askance upon the Files series, in which fleeting pecks bestowed on Nancy by her longtime steady, Ned Nickerson, give way to lingering embraces in a Jacuzzi."[7] Cover art for Files titles, such as Hit and Run Holiday (1986), reflects these changes; Nancy is often dressed provocatively, in short skirts, shirts that reveal her stomach or breasts, or a bathing suit. She is often pictured with an attentive, handsome male in the background, and frequently appears aware of and interested in that male. Nancy also becomes more vulnerable, being often chloroformed into unconsciousness, or defenseless against chokeholds.[61] The books place more emphasis on violence and character relationships, with Nancy Drew and Ned Nickerson becoming a more on-off couple, and both having other love interests that can span multiple books.

The Files also launched its own spin off. A crossover spin-off series with The Hardy Boys, titled the Supermystery series, began in 1988. These books were in continuity with the similar Hardy Boys spin-off, The Hardy Boys Casefiles.

In 1995, Nancy Drew finally goes to college in the Nancy Drew on Campus series. These books read more similar to soap opera books, such as the Sweet Valley High series. The On Campus books focus more on romance plots, and also centered around other characters; the mysteries were merely used as subplots. By reader request, Nancy broke off her long-term relationship with boyfriend Ned Nickerson in the second volume of the series, On Her Own (1995).[36][62] Similar to the Files series, reception for the On Campus series was also mixed, with some critics viewing the inclusion of adult themes such as date rape "unsuccessful".[63][64] Carolyn Carpan commented that the series was "more soap opera romance than mystery" and that Nancy "comes across as dumb, missing easy clues she wouldn't have missed in previous series".[65] The series was also criticized for focusing more on romance than on grades or studying, with one critic stating that the series resembled collegiate academic studying in the 1950s, where "women were more interested in pursuing ... the "MRS" degree."[66]

In 1997, Simon & Schuster announced a mass cancellation of Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys spin-offs, except ones for younger children. The Files series ran until the end of 1997, while both the Supermystery and on Campus series ran until the beginning of 1998.

2003–2012: Girl Detective and Graphic Novels

In 2003, publishers Simon & Schuster decided to end the original Nancy Drew series and feature Nancy's character in a new mystery series, Girl Detective. The Nancy Drew of the Girl Detective series drives a hybrid car, uses a mobile phone, and recounts her mysteries in the first person. Many applaud these changes, arguing that Nancy has not really changed at all other than learning to use a cell phone.[67] Others praise the series as more realistic; Nancy, these commentators argue, is now a less-perfect and therefore more likable being, one whom girls can more easily relate to – a better role model than the old Nancy because she can actually be emulated, rather than a "prissy automaton of perfection."[68]

Some, mostly fans, vociferously lament the changes, seeing Nancy as a silly, air-headed girl whose trivial adventures (discovering who squished the zucchini in Without a Trace (2004)) "hold a shallow mirror to a pre-teen's world."[69] Leona Fisher argues that the new series portrays an increasingly white River Heights, partially because "the clumsy first-person narrative voice makes it nearly impossible to interlace external authorial attitudes into the discourse", while it continues and worsens "the implicitly xenophobic cultural representations of racial, ethnic, and linguistic others" by introducing gratuitous speculations on characters' national and ethnic origins.[70]

The character is also the heroine of a series of graphic novels, begun in 2005 and produced by Papercutz. The graphic novels are written by Stefan Petrucha and illustrated in manga-style artwork by Sho Murase. The character's graphic novel incarnation has been described as "a fun, sassy, modern-day teen who is still hot on the heels of criminals."[71]

When the 2007 film was released, a non-canon novelization of the movie was written to look like the older books. Two books were also written for the Girl Detective and Clue Crew series, both of which deal with a mystery on a movie set. In 2008, the Girl Detective series was re-branded into trilogies and to have a model on the cover. These mysteries became deeper, with the mystery often spread across three books, and multiple culprits. These trilogies were also met with negative fan reception due to Nancy's constant mistakes, shortness of the books, and lack of action. With the new trilogy format, sales began slipping. In 2010, Simon & Schuster then cut back from six Nancy Drew books per year, to four books per year. In December 2011, they finally announced that the series was cancelled along with the Hardy Boys Undercover Brothers series.

2013–present: Diaries

With the sudden cancellation of the Girl Detective series, Simon & Schuster needed to find new Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys series. The Diaries series began in 2013.

Although her age is not mentioned, Nancy is about eighteen years old (she appears to be about thirteen to fourteen on the cover art). However, Nancy has certain freedoms of an eighteen year old (a nonrestrictive license, college-aged boyfriend, travels without supervision), and while her immature appearance is not commented on, her speech and actions are written as someone in their late teens.

The series is similar to its predecessor, in that the books are narrated in first person, Nancy is still absent-minded and awkward, and references are made to pop culture and technology (with mixed accuracy). Situations and problems in typical "tween books" are also carried over to this series. In contrast to the Girl Detective series, Nancy is written with in more juvenile voice, and does not navigate the world of adults as in previous incarnations. In addition, Nancy is found to have a lack of motivation in solving mysteries — Nancy often states she is avoiding mysteries, or is "on a break" from sleuthing; Nancy also can act timid and scared at times. These continued attempts to make Nancy's character more modern and less perfect have resulted in a confusing, and often conflicting, representation of the iconic Nancy Drew character.

Like the Girl Detective series, the Diaries series has received negative fan reception. Now in addition to the same issues the Girl Detective books faced, the Diaries faces even more criticism. The series continues the criticism of Nancy's change in character, dull and exaggerated end-chapter cliffhangers, and several continuity errors. New additions to criticism involve: the lack of differing types of mysteries, with most books being about sabotage; titles unrelated or too vague to fit the story; and the waving quality of the ghostwriters, which vary from book to book, being more notable and obvious. The biggest new criticism, though, is Nancy's refusal to solve mysteries, and how often a mystery is solved not due to Nancy's skills, but due to it being solved by a secondary character.

Specific examples about criticism of the series lie in two specific books: The Sign in the Smoke (#12), and The Haunting on Heliotrope Lane (#16). In The Sign in the Smoke, Nancy refuses to solve the mystery until partway through; and it was not Nancy who actually solved the case, but a secondary character. In The Haunting on Heliotrope Lane, fans complain Nancy and her friends act out-of-character, and that there are frequent mentions of Nancy and her friends being scared, screaming, or "peeing their pants".

As more books came out, fans of the character began comparing it to its Hardy Boys counterpart, The Hardy Boys Adventures, and concluded that the problems that existed in the Diaries series did not exist in the Adventures series. Fans have pointed out that the Adventures stories are well-written, with varying storylines, and competent protagonists, who do not complain about solving mysteries; in addition, it has been noted that The Hardy Boys are able to do more activities, and be involved in more dangerous situations, as boys, while Nancy, a female, is not able to. This has led to some suspecting Simon & Schuster may be gender stereotyping.

Other characters in the series

Carson Drew

Carson Drew is Nancy's father, an idealized father figure and a handsome widower, who is former district attorney now working in private practice.[72] His wife, Nancy's mother, died when Nancy was only three.

He is a progressive parent, encouraging Nancy's independence and self-reliance.[73] He often enlists the help of his daughter for many of his cases, and he often assists her in many of her cases, offering guidance both professionally and as a father.

He also makes good use of his professional connections and privileges to help Nancy solve her cases. He frequently leaves Nancy to her sleuthing while he travels on business (throughout the book series, he frequently goes away on business trips). On numerous occasions, Nancy has had to save her father from danger, including several kidnappings. Mr. Drew is always proud of Nancy when she has solved, and finished a case.

In the films of the 1930s he is played by John Litel. In the films Carson Drew is a far more patrician and authoritarian figure than in the books. [74] In the 2007 film he was played by Tate Donovan.

Hardy Boys

George Fayne

Ned Nickerson

Ghostwriters

Consistent with other Stratemeyer Syndicate properties, the Nancy Drew novels were written by various writers, all under the pen name Carolyn Keene.[75] In accordance with the customs of Stratemeyer Syndicate series production, ghostwriters for the Syndicate signed contracts that have sometimes been interpreted as requiring authors to sign away all rights to authorship or future royalties.[76] Contracts stated that authors could not use their Stratemeyer Syndicate pseudonyms independently of the Syndicate.[77] In the early days of the Syndicate, ghostwriters were paid a fee of $125, "roughly equivalent to two month's wages for a typical newspaper reporter, the primary day job of the syndicate ghosts."[78]

During the Great Depression this fee was lowered to $100 and eventually $75.[79] All royalties went to the Syndicate, and all correspondence with the publisher was handled through a Syndicate office. The Syndicate was able to enlist the cooperation of libraries in hiding the ghostwriters' names; when Walter Karig, who wrote volumes eight through ten of the original Nancy Drew Mystery Stories, tried to claim rights with the Library of Congress in 1933, the Syndicate instructed the Library of Congress not to reveal the names of any Nancy Drew authors, a move with which the Library of Congress complied.[80]

The Syndicate's process for creating the Nancy Drew books consisted of creating a detailed plot outline, drafting a manuscript, and editing the manuscript. Edward Stratemeyer and his daughters Harriet Adams and Edna Stratemeyer Squier wrote most of the outlines for the original Nancy Drew series until 1979. Volume 30, The Clue of the Velvet Mask (1953), was outlined by Andrew Svenson. Usually, other writers wrote the manuscripts. Most of the early volumes were written by Mildred Wirt Benson.[81] Other volumes were written by Walter Karig, George Waller, Jr., Margaret Scherf, Wilhelmina Rankin, Alma Sasse, Charles S. Strong, Iris Vinton,[82] and Patricia Doll. Edward Stratemeyer edited the first three volumes, and Harriet Adams edited most subsequent volumes until her death in 1982. In 1959, the earlier titles were revised, largely by Adams.[83] From the late 1950s until her death in 1982, Harriet Adams herself wrote the manuscripts for most of the books.[84]

After Adams's death, series production was overseen by Nancy Axelrad (who also wrote several volumes). The rights to the character were sold in 1984, along with the Stratemeyer Syndicate itself, to Simon & Schuster. Book packager Mega-Books subsequently hired authors to write the main Nancy Drew series and a new series, The Nancy Drew Files.[56]

Legal disputes

In 1980, Harriet Adams switched publishers to Simon & Schuster, dissatisfied with the lack of creative control at Grosset & Dunlap and the lack of publicity for the Hardy Boys' 50th anniversary in 1977. Grosset & Dunlap filed suit against the Syndicate and the new publishers, Simon & Schuster, citing "breach of contract, copyright infringement, and unfair competition."[85]

Adams filed a countersuit, claiming the case was in poor taste and frivolous, and that, as author of the Nancy Drew series, she retained the rights to her work. Although Adams had written many of the titles after 1953, and edited others, she claimed to be the author of all of the early titles. In fact, she had rewritten the older titles and was not their original author. When Mildred Benson was called to testify about her work for the Syndicate, Benson's role in writing the manuscripts of early titles was revealed in court with extensive documentation, contradicting Adams' claims to authorship. The court ruled that Grosset had the rights to publish the original series as they were in print in 1980, but did not own characters or trademarks. Furthermore, any new publishers chosen by Adams were completely within their rights to print new titles.[86]

Evolution of character's appearance

Nancy Drew has been illustrated by many artists over the years, and her look constantly updated. Both the Stratemeyer Syndicate and the books' publishers have exercised control over the way Nancy is depicted.[87]

Jennifer Stowe contends that Nancy's portrayal devolves significantly over the years:

The 1930s Nancy Drew is characterized as bold, capable and independent. She actively seeks out clues, and is shown in the center of the compositions. In subsequent characterizations Nancy Drew becomes progressively weaker, less in control. By the 1990s there is a complete reversal in the representation of her character. She is often shown being chased or threatened, the confidence of 1930s being replaced by fear.[88]

Some aspects of Nancy's portrayal have remained relatively constant through the decades. Arguably her most characteristic physical depiction is that she is shown holding a flashlight.[89]

Russell H. Tandy

Commercial artist Russell H. Tandy was the first artist to illustrate Nancy Drew. Tandy was a fashion artist and infused Nancy with a contemporary fashion sensibility: her early style is that of a flatfoot flapper: heeled Mary Janes accompany her blue flapper skirt suit and cloche hat on three of the first four volume dust jackets. As styles changed over the next few years, Nancy began to appear in glamorous frocks, with immaculately set hair, pearls, matching hats, gloves, and handbags.[90] By the 1940s, Nancy wore simpler, tailored suits and outfits; her hair was often arranged in a pompadour.[91] In the post-war era, Tandy's Nancy is shown hatless, wearing casual skirt and blouse ensembles, and carrying a purse, like most teens of the late 1940s.[92]

Tandy drew the inside sketches for the first 26 volumes of the series as well as painting the covers of the first 26 volumes with the exception of volume 11 – the cover artist for volume 11 is unknown. Tandy read each text before he began sketching, so his early covers were closely connected to specific scenes in the plots. He also hand-painted the cover lettering and designed the original Nancy Drew logo: a silhouette of Nancy bending slightly and looking at the ground through a quizzing glass.[92]

Tandy often portrays Nancy Drew with confident, assertive body language. She never appears "shocked, trepidatious, or scared".[93] Nancy is shown either boldly in the center of the action or actively, but secretively, investigating a clue.[94] She is often observed by a menacing figure and appears to be in imminent danger, but her confident expression suggests to viewers that she is in control of the situation.[95]

Tandy's home was struck by fire in 1962, and most of his original paintings and sketches were destroyed. As a result, the Tandy dust-jackets are considered very valuable by collectors.[96]

Bill Gillies and others

Beginning with Tandy in 1948 and continuing into the early 1950s, Nancy's appearance was updated to follow the current styles. In postwar opulence, a trend emerged for young adults to have their own casual style, instead of dressing in the same styles as more mature adults, and Nancy becomes less constrained. Sweater or blouse and skirt ensembles, as well as a pageboy hairstyle, were introduced in 1948, and continued with new artist Bill Gillies, who updated 10 covers and illustrated three new jackets from 1950 to 1952. Gillies used his wife for a model, and Nancy reflects the conservative 1950s, with immaculately waved hair and a limited wardrobe – she wears similar sweater, blouse, and skirt ensembles, in different combinations, on most of these covers. Gillies also designed the modern-era trademark as a spine symbol which was used for decades: Nancy's head in profile, looking through a quizzing glass.[96]

In the later Tandy period (1946 – 1949) and continuing throughout the 1950s, Nancy is depicted less frequently in the center of the action. The Ghost of Blackwood Hall shows an assertive Nancy leading more timid friends up the front steps of the haunted house, and marks a transition to later illustrations. From 1949 forward, she is likely to be observing others, often hiding or concealing herself.[97] Her mouth is often open in surprise, and she hides her body from view.[98] However, although Nancy "expresses surprise, she is not afraid. She appears to be a bit taken aback by what she sees, but she looks as if she is still in control of the situation."[95] Many of these covers feature Nancy poised in the observation of a clue, spying on criminal activity, or displaying her discoveries to others involved in the mystery. Only occasionally is she shown in action, such as running from the scene of a fire, riding a horse, or actively sleuthing with a flashlight. At times she is only involved in action as her hiding place has been discovered by others. In most cases, more active scenes are used for the frontispiece, or in books after 1954, illustrations throughout the text drawn by uncredited illustrators.

Rudy Nappi and others

Joseph Rudolf "Rudy" Nappi, the artist from 1953 to 1979, illustrated a more average teenager. Nappi was asked by Grosset & Dunlap's art director to update Nancy's appearance, especially her wardrobe. Nappi gave Nancy Peter Pan collars, shirtwaist dresses, a pageboy (later a flip) haircut, and the occasional pair of jeans. Nancy's hair color was changed from blonde to strawberry-blonde, reddish-blonde, or titian by the end of the decade. The change was long rumored to have been the result of a printing ink error, but was considered so favorable that it was adopted in the text for books published after 1959, and by illustrator Polly Bolian for volumes she created for a special book club in 1959–60.[99]

In 1962, all Grosset & Dunlap books become "picture covers", books with artwork and advertising printed directly on their covers, as opposed to books with a dust jacket over a tweed volume. The change was to reduce production costs. Several of the 1930s and 1940s cover illustrations were updated by Nappi for this change, depicting a Nancy of the Kennedy era, though the stories themselves were not updated. Internal illustrations, which were dropped in 1937, were returned to the books beginning in 1954, as pen and ink line drawings, mostly by uncredited artists, but usually corresponding with Nappi's style of drawing Nancy on the covers.[36] Nappi followed trends initiated by Gillies and often illustrated Nancy wearing the same clothing more than once, including a mustard shirtwaist dress.

Unlike Tandy, Nappi did not read the books before illustrating them; instead, his wife read them and provided him with a brief plot summary before Nappi began painting.[100] Nappi's first cover was for The Clue of the Velvet Mask, where he began a trend of portraying Nancy as "bobby-soxer ... a contemporary sixteen-year-old. This Nancy was perky, clean-cut, and extremely animated. In the majority of his covers Nancy looks startled – which, no doubt, she was."[101] Nancy's style is considerably conservative, and remains so during the psychedelic period. Although she wears bold colors and prints, or the background colors are shades of electric yellow, shocking pink, turquoise, or apple green, her clothing is high-necked and with long hemlines. Earlier Nappi covers show Nancy in poses similar to those in the covers by Tandy and Gillies; for many updated covers he simply updated the color scheme, clothing style, and hairstyles of the characters but retains their original poses in similar settings. Later Nappi covers show only Nancy's head or part of her body, surrounded by spooky or startling elements or clues from the story. These Nappi covers would later be used for the opening credits of the television production, with photos of Pamela Sue Martin inserted on the book covers.

Often, "Nancy's face wears the blank expression of one lost in thought,"[102] making her appear passive.[103] On the cover of The Strange Message in the Parchment (1977), for example, in contrast to earlier covers, Nancy "is not shown in the midst of danger or even watching a mystery unfold from a distance. Instead, Nancy is shown thinking about the clues";[104] in general, Nancy becomes less confident and more puzzled.[102]

Nancy in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s

Ruth Sanderson and Paul Frame provided cover art and interior illustrations for the first Nancy Drew paperbacks, published under the Wanderer imprint. Other artists, including Aleta Jenks and others whose names are unknown,[105] provided cover art, but no interior illustrations, for later paperbacks. Nancy is portrayed as "a wealthy, privileged sleuth who looks pretty and alert.... The colors, and Nancy's facial features, are often so vivid that some of the covers look more like glossy photographs than paintings."[106]

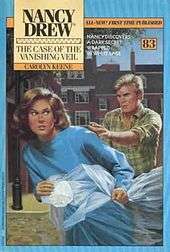

Nancy is frequently portrayed pursuing a suspect,[103] examining a clue, or observing action. She is often also shown in peril:[107] being chased, falling off a boat, or hanging by a rope from rafters. These covers are "characterized by frenetic energy on Nancy's part; whether she is falling, limbs flailing, an alarmed look on her face, or whether she is running, hair flying, body bent, face breathless. Nancy does not have any control over the events that are happening in these covers. She is shown to be a victim, being hunted and attacked by unseen foes."[108]

Nancy is also sometimes pursued by a visibly threatening foe, as on the cover of The Case of the Vanishing Veil (1988).

The covers of The Nancy Drew Files and Girl Detective series represent further departures from the bold, confident character portrayed by Tandy. The Nancy portrayed on the covers of The Nancy Drew Files is "a markedly sexy Nancy, with a handsome young man always lurking in the background. Her clothes often reveal an ample bustline and her expression is mischievous."[106] In the Girl Detective series, Nancy's face is depicted on each cover in fragments. Her eyes, for example, are confined to a strip across the top of the cover while her mouth is located near the spine in a box independent of her eyes. The artwork for Nancy's eyes and mouth is taken from Rudy Nappi's cover art for the revised version of The Secret of the Old Clock.[36]

Books

The longest-running series of books to feature Nancy Drew is the original Nancy Drew series, whose 175 volumes were published from 1930 to 2003. Nancy also appeared in 124 titles in The Nancy Drew Files and is currently the heroine of the Diaries series. Various other series feature the character, such as the Nancy Drew Notebooks and Nancy Drew on Campus. While Nancy Drew is the central character in each series, continuity is preserved only within one series, not between them all; for example, in concurrently published titles in the Nancy Drew series and the Nancy Drew on Campus series, Nancy is respectively dating her boyfriend Ned Nickerson or broken up with Ned Nickerson. The two exceptions are the A Nancy Drew And Hardy Boys SuperMystery series that ran concurrently with the Files, and shares continuity with those stories and the then-running Hardy Boys Casefiles, and in 2007 a new A Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys Super Mystery series shared continuity with both the Girl Detective series.

Nancy Drew Diaries is the current series and started in 2013. This is a reboot of the Nancy Drew: Girl Detective series. The series is described as "A classic Nancy Drew with her modern twist". While similar to the Nancy Drew, Girl Detective series, this series includes situations and problems typical in young adult "tween" books. The mystery element is not always the main focus of the characters, and often Nancy states she is avoiding mysteries or "on a break" from sleuthing. Nancy often acts timid and scared, in book #16 The Haunting on Heliotrope Lane she says she is glad she "hasn't peed herself from being scared". This Nancy does not navigate in the world of adults as previous versions of the character. The first person narration reveals a juvenile voice with a passive role in the action and a lack of motivation in solving mysteries. In book #12 The Sign in the Smoke Nancy does not solve the mystery, a secondary character comes up with the solution. In several books Nancy stumbles upon the solution to the "mystery" and acts amazed at the reveal. This is in contrast to the set-up of previous Nancy Drew series. Attempts to make Nancy's character more modern and less perfect have resulted in a confusing and often conflicting representation of the iconic Nancy Drew character.

International publications

The main Nancy Drew series, The Nancy Drew Files, and Girl Detective books have been translated into a number of languages besides English. Estimates vary from between 14 and 25 languages,[109] but 25 seems the most accurate number.[110] Nancy Drew books have been published in many European countries (especially in Nordic countries and France) as well as in Latin America and Asia. The character of Nancy Drew seems to be more popular in some countries than others. Nancy Drew books have been in print in Norway since 1941 (the first country outside USA[111]), in Denmark since 1958, in France since 1955[112] and in Italy since 1970 by Arnoldo Mondadori Editore. Other countries, such as Estonia, have only recently begun printing Nancy Drew books.[110]

Nancy's name is often changed in translated editions: in France, she is known as Alice Roy; in Sweden, as Kitty Drew; in Finland, as Paula Drew;[110] and in Norway the book series has the name of Frøken Detektiv (Miss Detective), though the heroine's name is still Nancy Drew inside the books.[113] In Germany, Nancy is a German law student named Susanne Langen. George Fayne's name is even more frequently changed, to Georgia, Joyce, Kitty, or Marion. Cover art and series order is often changed as well, and in many countries only a limited number of Drew books are available in translation.

In other media

Five feature films, two television shows, and four television pilots featuring Nancy Drew have been produced to date. No television show featuring Nancy Drew has lasted longer than two years, and film portrayals of the character have met with mixed reviews.

Films

Bonita Granville

In 1937, Warner Bros. bought the rights to the Nancy Drew book series from the Stratemeyer Syndicate, for a reported $6,000. Warner Bros. wanted to make a series of B-films based on the character, to serve as a companion to their popular Torchy Blane B-film series, which starred Glenda Farrell, Barton MacLane, and Tom Kennedy. Adams sold the rights to Jack L. Warner without an agent or any consultation; thus, she sold all and any film rights to Warner Bros., a move she would later regret, and would later come into question by her publishers.

The films were in part based on the Torchy Blane film series with Glenda Farrell and Barton MacLane, also made by Warner Bros. Nancy & Torchy have very similar hair styles, almost always wear a hat, were told to stay off the case (but were stubborn and continued to sleuth), were assisted by their boyfriends, and even had the same writers.

Warner Bros. cast 15-year-old Bonita Granville to portray Nancy, and utilized the same three-lead system that Torchy Blane used; John Litel portrayed Nancy's father, Carson Drew; and Frankie Thomas portrayed Ned Nickerson, whose name was changed to Ted to help the series be more up-to-date and mainstream. However, also like Torchy, the series retained several recurring characters: Renie Riano portrayed housekeeper Effie Schneider, while Frank Orth portrayed bumbling police captain, Captain Tweedy. Director William Clemens directed the series, while Torchy Blane writer Kenneth Gamet wrote the screenplays and some original story ideas.

From 1938 to 1939, four films featuring Nancy were released:

- Nancy Drew... Detective (November 1938)

- Loosely based on The Password to Larkspur Lane

- Nancy Drew... Reporter (February 1939)

- Nancy Drew… Trouble Shooter (June 1939)

- Nancy Drew and the Hidden Staircase (September 1939)

- Loosely based on The Hidden Staircase

A fifth movie was written, and may have been produced, but it was never released. Frankie Thomas believes that he and Granville made five films, not four,[114] and in August 1939, Nancy Drew editor Harriet Adams wrote to ghostwriter Mildred Benson, "three have been shown in this area, and I have just heard that a fifth is in production."[115] The cancellation of the series was a result of Bonita Granville leaving Warner Bros. for MGM. Warner Bros. also decided to discontinue the Torchy Blane series, after its star Glenda Farrell left the studio as well.

These films took many liberties from the book series casting-wise. Red-haired Granville's portrayal of the then-blonde Nancy was portrayed to be ditzy, absent-minded, and more meddling than that of the ongoing book series. While the Carson Drew of the books was portrayed as older, feeble, and more of a hands-off parent, John Litel's Carson was young and handsome, much more athletically fit, and tried his best to restrain Nancy from getting into danger. Ned/Ted was even more drastically altered: instead of being Nancy's boyfriend in college who lives in a different town, he was now her next-door neighbor, who was a year older than her and their romance was very ambiguous and tumultuous. The recurring character of the older Hannah Gruen was replaced with Effie Schneider, a minor character in the books who was Hannah's teenage niece. Effie and Hannah's characteristics were merged, although Effie's fidgety, frightful nature retained prominence for comedic effect. In addition to these four, new character Captain Tweedy was added, to portray the stereotypical bumbling, clueless cop that mirrored Steve McBride in the Torchy Blane series. The characters of Bess Marvin, George Fayne, and Helen Corning, did not appear in the film series, and never mentioned or referred to.

In addition to the cast changes, the tone and pacing of the films was also matured and altered for comic effect and to accommodate a wider audience. The films changed the petty crimes of the books into gruesome murders, that are often spearheaded by dangerous criminals. At the time of the films, Nancy and Ned/Ted's romance in the books was set aside for the main mystery; on the other hand, romance was a prominent theme of the films, with Nancy being portrayed as the domineering girlfriend, and Ted as the repressive boyfriend, usually used by Nancy to his misery. While book Nancy was usually treated with authority and equal respect to other adults, Nancy in the films was often chastised by adults for her habit to go into mysteries, and she often found herself at odds with her father and the police.

To promote the film, Warner Bros. created a Nancy Drew fan club that included a set of rules, such as: "Must have steady boy friend, in the sense of a 'pal'" and must "Take part in choosing own clothes."[116] These rules were based on some research Warner Bros. had done on the habits and attitudes of "typical" teenage girls.[117] Granville was the "honorary president" of the fan club, and a kit for the club came with autographed pictures of her.

Critical reaction to these films is mixed. Some find that the movies did not "depict the true Nancy Drew",[118] in part because Granville's Nancy "blatantly used her feminine wiles (and enticing bribes)" to accomplish her goals.[119] The films also portray Nancy as childish and easily flustered, a significant change from her portrayal in the books.[120] Just as with the critics, both ghostwriter Mildred Wirt Benson and editor Harriet Adams were also divided on the film's reception. Adams did not like the films, and resented the studio for its treatment of the character; she did, however, keep a personal autographed photo from Granville on her office desk for many years. Contrary to Adams, Benson liked the films of the time.[115]

Granville stated her favorite film of the series was Nancy Drew… Trouble Shooter. Twenty years after the films, Thomas would later go on to portray Carson Drew in a failed pilot.

Emma Roberts

A new film version for Nancy Drew had been in the works at Warner Bros. since the mid 1990s. However, nothing came into fruition until the mid 2000s.

A film adaptation of Nancy Drew was released on June 15, 2007 by Warner Bros. Pictures, with Emma Roberts as Nancy Drew, Max Thieriot as Ned Nickerson and Tate Donovan as Carson Drew. Andrew Fleming directed the film, while Jerry Weintraub produced. As with the earlier Drew films, reactions were mixed. Some see the film as updated version of the basic character: "although it has been glammed up for the lucrative tween demographic, the movie retains the best parts of the books, including, of course, their intelligent main character."[121] Others find the movie "jolting" because Nancy's "new classmates prefer shopping to sleuthing, and Nancy's plaid skirt, penny loafers, and magnifying glass make her something of a dork, not the town hero she was in the Midwest."[122]

Before the release of the 2007 film, Roberts was set to star in two other Nancy Drew films by Warner Bros. These films would also be produced by Weintraub. However, after the mixed success of the first film and Roberts' desire to move onto other projects, these sequels were never made.

Sophia Lillis

On April 20, 2018, Warner Bros. announced they were doing a new Nancy Drew film series, starring Sophia Lillis as Nancy. The first film will be adapted from The Hidden Staircase, with Ellen DeGeneres and Wendy Williams among the producers. The film will not be related to the previous film starring Bonita Granville.[123][124]

Television

The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries

The most successful attempt at bringing Nancy Drew to life was The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries, which ran from 1977 to 1979 on ABC.[125] Future Dynasty star Pamela Sue Martin starred as Nancy, with Jean Rasey and George O'Hanlon, Jr. as friends George and Ned, and William Schallert as Carson Drew.

This series is regarded as the most faithful series to the books; Martin is often regarded by many Nancy Drew fans as the best actress to portray her. The series was also faithful in its tone of smaller mysteries, such as haunted houses or theft.

The first season originally alternated with The Hardy Boys; The Hardy Boys was met with success, but the Drew episodes were met with mixed results. In the second season, the format shifted to present The Hardy Boys as the more prominent characters, with Nancy Drew mostly a character in crossover episodes (although the character did have some solo episodes). Martin, who was 24 years old at the start of the series, left midway through the season, and was replaced by 19-year-old Janet Louise Johnson for the final few episodes.[126]

When the series came back for a third season, Nancy Drew was dropped from the series, with it now focusing completely on The Hardy Boys. But soon after the change, ABC cancelled the series.

Nancy Drew (1995 TV series)

Nelvana began production of another Nancy Drew television show in 1995. Tracy Ryan starred as Nancy Drew, with Jhene Erwin as Bess Marvin, Joy Tanner as George Fayne, and, in a recurring role, Scott Speedman as Ned Nickerson. Nancy is now a 21-year-old criminology student, moving to New York City and living in upscale apartment complex "The Callisto". Nancy solved various mysteries with Bess, a gossip columnist at The Rag, and George, a mail carrier and amateur filmmaker. Ned worked on charity missions in Africa, but did make a few appearances. This Nancy Drew series was again partnered with a series based on The Hardy Boys, with Ryan appearing in two episodes as Nancy. Both shows were cancelled midway through their first seasons due to low ratings; the poorly syndicated half-hour shows aired in a slot outside of prime time on the new The WB and UPN networks.[127] The entire series has since been released on DVD, and has appeared on several online streaming sites.

List of episodes

| # | Episode Title | Air date |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Welcome to the Callisto | September 23, 1995 |

| 2 | Happy Birthday, Nancy | September 30, 1995 |

| 3 | Exile | October 7, 1995 |

| 4 | Asylum | October 14, 1995 |

| 5 | The Ballad of Robin Hood | October 21, 1995 |

| 6 | Bridal Arrangements | October 28, 1995 |

| 7 | The Death and Life of Billy Feral | November 4, 1995 |

| 8 | Double Suspicion | November 11, 1995 |

| 9 | The Stranger by the Road | November 18, 1995 |

| 10 | Photo Finish | November 25, 1995 |

| 11 | Who's Hot, Who's Not | December 2, 1995 |

| 12 | Fashion Victim | December 9, 1995 |

| 13 | The Long Journey Home | December 16, 1995 |

Nancy Drew (2002 film)

On December 15, 2002, ABC aired Nancy Drew, starring Maggie Lawson and produced by Lawrence Bender. The movie was intended to be a pilot for a possible weekly series, which saw Nancy and her friends going off to college in a modern setting, and Nancy pursuing a journalism degree. Like the 1930s films, this pilot also took a more mature turn, with the mystery being a drug bust, and Nancy having a falling out with her father. The pilot aired as part of The Wonderful World of Disney series, with additional scripts being ordered and production contingent on the movie's ratings and reception. The series was passed at ABC, and UPN also passed following Lawson being cast on another ABC series.[128]

Drew

On October 5, 2015, CBS announced that it would be developing a new series titled Drew.[129] In January 2016, they announced that the pilot would feature Nancy as a non-Caucasian New York City police detective in her thirties.[130] The pilot episode will revolve around Nancy investigating the death of Bess Marvin, who had died six months previously.[131] The cast for this pilot included:[132][133][134][135][136][137]

- Sarah Shahi as Nancy Drew

- Anthony Edwards as Carson Drew

- Vanessa Ferlito as George Fayne

- Felix Solis as Lieutenant Ford

- Steve Kazee as Ned Nickerson

- Debra Monk as Hannah Gruen

The pilot was written by Joan Rater and Tony Phelan and directed by James Strong.[137] The pilot was shot in March 2016, on location in New York City.[138] During this time, Phelan and Rater had another pilot, Doubt, which many television reporters often placed in competition for a series order with Drew. On May 14, 2016, it was announced that CBS decided to order Doubt, and pass on the Drew pilot, so CBS Studios could shop it to other networks for series consideration.[139][140][141] Ultimately, the series was not picked up by any other network. Sarah Shahi and producer Tony Phelan later admitted the pilot was not in good quality.[142][143]

Other failed attempts

In 1957, Desilu and CBS developed a show, Nancy Drew, Detective, based on the movies from the 1930s. Roberta Shore was cast in the title role as Nancy Drew, with Tim Considine as Ned Nickerson, and Frankie Thomas, Jr. as Carson Drew. Thomas had previously starred in the film series in Considine's role. Although a pilot was produced in April 1957, the series could not find a sponsor. With legal troubles and the disapproval of Harriet Adams, the idea of a series was eventually abandoned.[144][145]

In October 1989, Canadian production company Nelvana began filming for a 13-episode Nancy Drew television series called Nancy Drew and Daughter for USA Network. Margot Kidder was cast as an adult Nancy Drew, and her daughter, Maggie McGuane, was cast as Nancy's daughter. However, Kidder was injured during filming of the first episode when the brakes failed on the car she was driving. The pilot was not finished, and the series was cancelled.[146][147]

On October 16, 2017, NBC announced that it would be developing a brand new Nancy Drew TV series.[148][143][149] Tony Phelan and Joan Rater will once again be writing, with Dan Jinks executive producing again for CBS Studios. However, this pilot will have a different plot and cast than the team's previous effort. Ultimately this series did not make it past the development stage, and a pilot was never made.[150] This pilot would have seen Nancy (now a middle-aged woman), who has written her own adventures as books, but must team up with her estranged former friends to solve a mystery.[143]

Video games

Computer games publisher Her Interactive began publishing Nancy Drew computer games in 1998. Some game plots are taken directly, or loosely taken, from the published Nancy Drew books, such as The Secret of the Old Clock; others are completely new ideas and are written by the Her Interactive staff. The games are targeted for a younger audience with the rating of "ages 10 and up" and are rated "E" ("Everyone") by the ESRB. They follow the popular adventure game style of play. Players move Nancy by pointing and clicking with the mouse around in a first person virtual environment to talk to suspects, pick up clues, solve puzzles, and eventually solve the crime.[151]

Lani Minella has voiced the Nancy character since the first game in 1998 up to the most recent game, Sea of Darkness, the 32nd game. The 33rd game, Midnight in Salem, will be voiced by a new actress. Minella, who has voiced Nancy for 17 years, was let go from the role. Her Interactive said that the community has been nothing but supportive of Minella, and that their overall goal is to keep creating noteworthy games.[152]

The most recent game has won various awards. For example: Sea of Darkness was a Mom’s Choice Award Gold Winner in February 2016 as well as a Cool Tool Award finalist for EdTech in 2016.

In addition to the games created by Her Interactive, a game for the Nintendo DS was released in September 2007 by Majesco Entertainment. In the game, developed by Gorilla Systems Co and called Nancy Drew: Deadly Secret of Olde World Park, players help Nancy solve the mystery of a missing billionaire.[153][154] Majesco has also released two other Nancy Drew games for the DS, titled Nancy Drew: The Mystery of the Clue Bender Society (released July 2008)[155] and Nancy Drew: The Hidden Staircase, based on the second book in the original Nancy Drew Mystery Stories series (released September 2008).[156] Nancy Drew: The Hidden Staircase and Nancy Drew: The Model Mysteries, both by THQ, are also available on the Nintendo DS system.

Some games, like Secrets Can Kill, Shadow at the Water's Edge, and The Captive Curse, are rated "E10+". The games have received recognition for promoting female interest in video games.[157] Her Interactive has also released several versions of their Nancy Drew games in French, as part of a series called Les Enquêtes de Nancy Drew,[110] and shorter games as part of a new series called the Nancy Drew Dossier.[158] The first title, Lights, Camera, Curses, was released in 2008 and the second, Resorting to Danger, was released in 2009. While most of the games are computer games, with most available only on PC and some newer titles also available on Mac, Her Interactive also have released some of the titles on other platforms, like DVD and Nintendo Wii system.

Her Interactive is currently in production of Nancy Drew: Midnight in Salem and is expected to release the game Spring 2019.

On May 13, 2016, Her Interactive introduced and released Nancy Drew: Codes & Clues, an application for iPad and iPhone along with Android devices. It was designed to help children develop skills in computer programming.

The app has also won a variety of awards:[159]

- Tillywig Toy & Media Awards – Brain Child Award Recipient

- Mom’s Choice Awards – Gold Award Recipient

- The National Parenting Center – Seal of Approval

- Kidscreen Awards 2017 – Nominee

Comic books

In March, 2017 Dynamite Entertainment released Anthony Del Col’s reboot of classic characters Nancy Drew and The Hardy Boys with NANCY DREW & THE HARDY BOYS: THE BIG LIE. Del Col has been a lifelong fan of the characters and was successful in working with Simon & Schuster to secure the comic book rights and then pitch to publishers.

Inspired by Archie Comics’ Afterlife with Archie, Del Col is quoted as saying, “So, then I started to think, 'Huh, I wonder what other characters are out there that are well-known that could be rebooted like that,'" Del Col said. "That's when I started to look around and I looked in some properties, and then I thought, 'Wait a minute. Nancy Drew. Hardy Boys. Oh, that would be really cool to do a hard-boiled noir take on them.' ”[160]

The series, a hardboiled noir take on the characters, finds characters Frank and Joe Hardy accused of murdering their father, Fenton Hardy, and turning to a femme fatale-esque Nancy Drew to clear their names. The series features artwork by Italian artist Werther Dell’Ederra with covers by UK artist Fay Dalton. Del Col credits editors Matt Idelson and Matt Humphreys with helping him shape the direction of the series.[161]

The series debuted to amazing reviews. Comics blog Readingwithaflightring.com declared it, “the best 'modern' approach to updating a franchise like this that I’ve seen. It works on every level and still fully embraces the heart of who they are."[162] Aintitcool.com reviewer Lyz Reblin stated, “The strength of the series thus far is Ms. Drew, who was absent for most of the first issue. She is a pitch-perfect modernized femme fatale, who could hold her own up against any present-day Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, or the like.”[163]

Merchandising

A number of Nancy Drew products have been licensed over the years, primarily in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. Parker Brothers produced a "Nancy Drew Mystery Game" in 1957 with the approval of the Stratemeyer Syndicate. In 1967 Madame Alexander produced a Nancy Drew doll. The doll carried binoculars and camera and was available in two outfits: with a plaid coat or a dress and short jacket. Harriet Adams disapproved of the doll's design, believing Nancy's face to be too childish, but the doll was marketed nonetheless. Various Nancy Drew coloring, activity, and puzzle books have also been published, as has a Nancy Drew puzzle. A Nancy Drew Halloween costume and a Nancy Drew lunchbox were produced in the 1970s as television show tie-ins.[164]

Cultural impact

According to commentators, the cultural impact of Nancy Drew has been enormous.[165] The immediate success of the series led directly to the creation of numerous other girls' mysteries series, such as The Dana Girls mystery stories and the Kay Tracey mystery stories,[166] and the phenomenal sales of the character Edward Stratemeyer feared was "too flip" encouraged publishers to market many other girls' mystery series, such as the Judy Bolton Series, and to request authors of series such as the Cherry Ames Nurse Stories to incorporate mystery elements into their works.[167]

Many prominent and successful women cite Nancy Drew as an early formative influence whose character encouraged them to take on unconventional roles, including U.S. Supreme Court Justices Sandra Day O'Connor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Sonia Sotomayor;[168] TV personalities Oprah Winfrey and Barbara Walters; singers Barbra Streisand and Beverly Sills;[169] mystery authors Sara Paretsky and Nancy Pickard; scholar Carolyn Heilbrun; actresses Ellen Barkin and Emma Roberts;[170] former Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton; former First Lady Laura Bush;[11] and former president of the National Organization for Women Karen DeCrow.[171] Less prominent women also credit the character of Nancy Drew with helping them to become stronger women; when the first Nancy Drew conference was held, at the University of Iowa, in 1993, conference organizers received a flood of calls from women who "all had stories to tell about how instrumental Nancy had been in their lives, and about how she had inspired, comforted, entertained them through their childhoods, and, for a surprising number of women, well into adulthood."[172]

Nancy Drew's popularity continues unabated: in 2002, the first Nancy Drew book published, The Secret of the Old Clock, alone sold 150,000 copies,[173] good enough for top-50 ranking in children's books,[174] and other books in the series sold over 100,000 copies each.[175] Sales of the hardcover volumes of the original Nancy Drew series alone has surpassed sales of Agatha Christie titles,[176] and newer titles in the Girl Detective series have reached The New York Times bestseller lists.[173] Entertainment Weekly ranked her seventeenth on its list of "The Top 20 Heroes" ahead of Batman, explaining that Drew is the "first female hero embraced by most little girls ... [Nancy lives] in an endless summer of never-ending adventures and unlimited potential." The magazine goes on to cite Scooby-Doo's Velma Dinkley as well as Veronica Mars as Nancy Drew's "copycat descendants".[89]

Many feminist critics have pondered the reason for the character's iconic status. Nancy's car, and her skill in driving and repairing it, are often cited. Melanie Rehak points to Nancy's famous blue roadster (now a blue hybrid) as a symbol of "ultimate freedom and independence."[169] Not only does Nancy have the freedom to go where she pleases (a freedom other, similar characters such as The Dana Girls do not have), but she is also able to change a tire and fix a flawed distributor, prompting Paretsky to argue that in "a nation where car mechanics still mock or brush off complaints by women Nancy remains a significant role model."[177]

Nancy is also treated with respect: her decisions are rarely questioned and she is trusted by those around her. Male authority figures believe her statements, and neither her father nor Hannah Gruen, the motherly housekeeper, "place ... restrictions on her comings and goings."[178] Nancy's father not only imposes no restrictions on his daughter, but trusts her both with her own car and his gun (in the original version of The Hidden Staircase [1930]), asks her advice on a frequent basis, and accedes to all her requests. Some critics, such as Betsy Caprio and Ilana Nash, argue that Nancy's relationship with her continually approving father is satisfying to girl readers because it allows them to vicariously experience a fulfilled Electra complex.[179]

Unlike other girl detectives, Nancy does not go to school (for reasons that are never explained, but assuming because she has finished), and she thus has complete autonomy. Similar characters, such as Kay Tracey, do go to school, and not only lose a degree of independence but also of authority. The fact of a character's being a school-girl reminds "the reader, however fleetingly, of the prosaic realities of high-school existence, which rarely includes high adventures or an authoritative voice in the world of adults."[180]

Some see in Nancy's adventures a mythic quality. Nancy often explores secret passages, prompting Nancy Pickard to argue that Nancy Drew is a figure equivalent to the ancient Sumerian deity Inanna and that Nancy's "journeys into the 'underground'" are, in psychological terms, explorations of the unconscious.[181] Nancy is a heroic figure, undertaking her adventures not for the sake of adventure alone, but in order to help others, particularly the disadvantaged. For this reason, Nancy Drew has been called the modern embodiment of the character of "Good Deeds" in Everyman.[182]

In the end, many critics[183] agree that at least part of Nancy Drew's popularity depends on the way in which the books and the character combine sometimes contradictory values, with Kathleen Chamberlain writing in The Secrets of Nancy Drew: "For over 60 years, the Nancy Drew series has told readers that they can have the benefits of both dependence and independence without the drawbacks, that they can help the disadvantaged and remain successful capitalists, that they can be both elitist and democratic, that they can be both child and adult, and that they can be both 'liberated' women and Daddy's little girls."[184] As another critic puts it, "Nancy Drew 'solved' the contradiction of competing discourses about American womanhood by entertaining them all."[185]

In 2010, Nancy Drew (and her novels) were discussed in the Young Adult themed issue of the academic journal Studies in the Novel. See Jennifer M. Woolston's essay titled "Nancy Drew's Body: The Case of the Autonomous Female Sleuth" for a detailed discussion of the heroine's impact on popular culture. The essay also discusses links to Nancy Drew and feminist theory.

Cultural References

- On the Fox television series Scream Queens, Chanel Oberlin (played by Emma Roberts) frequently refers to Grace Gardner (Skyler Samuels) as "Nancy Drew".

- On the CW television series Riverdale, Betty Cooper (Lili Reinhart) is a fan of the book series, and frequently mentions them in her own investigations throughout the series.

- Larissa Zageris and Kitty Curran wrote and illustrated a parody novel, The Secrets of the Starbucks Lovers, which featured singer Taylor Swift as the heroine, investigating threatening messages left on Starbucks cups.[186]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Voice Of Nancy Drew - Nancy Drew | Behind The Voice Actors". Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved February 18, 2018. Check mark indicates role has been confirmed using screenshots of closing credits and other reliable sources

- ↑ Peters (2007), 542.

- 1 2 Rehak (2006), 243.

- ↑ Nash (2006), 55.

- 1 2 Rehak (2006), 248.

- ↑ Lapin (1989).

- 1 2 Leigh Brown (1993), 1D.

- ↑ Stowe (1999).

- ↑ Inness (1997), 79.

- ↑ McFeatters (2005), 36.

- 1 2 Burrell (2007).

- ↑ Argetsinger and Roberts (2007), C03.

- ↑ Sherrie A. Inness writes that in "many respects, Nancy Drew exists as a wish fulfillment." See Inness (1997), 175.

- ↑ Chamberlain (1994).

- ↑ Fisher (2004), 71.

- ↑ Macleod (1995), 31.

- 1 2 Mason (1995), 50.

- ↑ Jones (1973), 708.

- ↑ Inness (1997), 91.

- ↑ Keene (1961), 198.

- ↑ Johnson (1982), xxvi.

- ↑ Johnson (1993), 12.

- ↑ Rehak (2006), 113–114.

- ↑ Rehak (2006), 113.

- ↑ Carpan (2008), 50.

- ↑ Quoted in Rehak (2006), 121.

- ↑ Kismaric and Heiferman (2007), 27.

- ↑ Quoted in Plunkett-Powell (1993), 18.

- ↑ Dyer and Romalov (1995), 194.

- ↑ See, for example, Betsy Caprio, Geoffrey Lapin, Karen Plunkett-Powell, and Melanie Rehak.

- ↑ See, for example, Maureen Corrigan, Catherine Foster.

- ↑ See, for example, Gerstel (2007), Kismaric and Heiferman (2007), and Plunkett-Powell (1993).

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 55.

- ↑ Kismaric and Heiferman (2007), 8.

- ↑ O'Rourke (2004).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fisher, "Nancy Drew, Sleuth."

- ↑ Kismaric and Heiferman (2007), 24.

- ↑ Quoted in Plunkett-Powell (1993), 33.

- ↑ While Benson stated repeatedly in interviews that Stratemeyer used these words to her (Keeline 25), James Keeline states that there is no independent confirmation of this; Stratemeyer's written comments to Benson upon receipt of the manuscript for The Secret of the Old Clock contain no such criticism (Keeline 26).

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 33.

- ↑ Quoted in Kismaric and Heiferman (2007), 28.

- ↑ See, for example, Kismaric and Heiferman (2007), Lapin (1986), and Fisher.

- ↑ while Mason's book was originally published in 1975, after the Drew books began to be revised and re-written, Mason cites the unrevised volumes almost exclusively.

- ↑ Mason (1995), 49.

- ↑ Mason (1995), 69–71.

- ↑ Mason (1995), 73.

- 1 2 Mason (1995), 60.

- ↑ Parry (1997), 148.

- ↑ Carpan (2008), 15.

- ↑ Mason (1995), 70.

- ↑ Keene (1956), 64. Quoted in Mason (1995), 70.

- ↑ Keene (1975), 35.

- ↑ Kismaric and Heiferman (2007), 94.

- ↑ Abate (2008), 167.

- ↑ Kismaric and Heiferman (2007), 113–114.

- 1 2 Plunkett-Powell (1993), 29.

- ↑ Keene (1985), 1.

- ↑ Keene (1985), 111–112. Cited by Shangraw Fox.

- ↑ Caprio (1992), 27.

- ↑ Torrance (2007), D01.

- ↑ Foster (1986), 31.

- ↑ Drew (1997), 185.

- ↑ Mitchell, Claudia (2007). Girl Culture: Studying girl culture : a readers' guide. Greenwood. p. 450. ISBN 0313339090.

- ↑ "NANCY DREW IS UPDATED - AND DATED". Akron Beacon Journal. September 21, 1995. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Carpan, Carolyn (2009). Sisters, Schoolgirls, and Sleuths. Scarecrow Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 0810863952.

- ↑ Johnson, Naomi (2008). Consuming Desires: A Feminist Analysis of Bestselling Teen Romance Novels. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. p. 18. ISBN 9780549324775.

- ↑ Springen and Meadows(2005).

- ↑ Benfer (2004), A15.

- ↑ Corrigan (2004).

- ↑ Fisher, Leona (2008), 73.

- ↑ "Sleuths Go Graphic" (2008).

- ↑ Ilana Nash (2006). American Sweethearts: Teenage Girls in Twentieth-century Popular Culture. Indiana University Press. pp. 36–. ISBN 0-253-21802-0.

- ↑ Sherrie A. Inness (1997). Nancy Drew and Company: Culture, Gender, and Girls' Series. Popular Press. pp. 175–. ISBN 978-0-87972-736-9.

- ↑ Ilana Nash (2006). American Sweethearts: Teenage Girls in Twentieth-century Popular Culture. Indiana University Press. pp. 79–. ISBN 0-253-21802-0.

- ↑ Andrews, Dale (2013-08-27). "The Hardy Boys Mystery". Children's books. Washington: SleuthSayers.

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 24.

- ↑ Keeline (2008), 21.

- ↑ Keeline (2008), 22.

- ↑ Rehak (2006), 149.

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 26–27.

- ↑ "Mildred Augustine Wirt Benson Papers". Iowa Women's Archives. University of Iowa Libraries. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 39.

- ↑ Rehak (2006), 245.

- ↑ Farah (2005), 431–521; Rehak (2006), 249.

- ↑ Johnson (1993), 16.

- ↑ Johnson (1993), 17.

- ↑ Rehak (2006), 228.

- ↑ Stowe (1999), 1.

- 1 2 "The Top 20 Heroes," Entertainment Weekly 1041 (April 3, 2009): 36.

- ↑ Stowe (1999), 15.

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 44.

- 1 2 Plunkett-Powell (1993), 43–44.

- ↑ Stowe (1999), 26.

- ↑ Stowe (1999), 28.

- 1 2 Stowe (1999), 32.

- 1 2 Plunkett-Powell (1993), 46.

- ↑ Stowe (1999), 30.

- ↑ Stowe (1999), 30–31.

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 48.

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 49.

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 47.

- 1 2 Stowe (1999), 35.

- 1 2 Stowe (1999), 36.

- ↑ Stowe (1999), 33.

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 52.

- 1 2 Plunkett-Powell (1993), 51.

- ↑ Stowe (1999), 38.

- ↑ Stowe (1999), 40.

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 160.

- 1 2 3 4 Shangraw Fox.

- ↑ "Around the World with Nancy Drew – Norway". Nancydrewworld.com. December 21, 2001. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ↑ (in French) Nancy Drew in France

- ↑ Skjønsberg (1994), 72.

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 117.

- 1 2 Kismaric and Heiferman (2007), 103.

- ↑ Kismaric and Heiferman (2007), 116.

- ↑ Nash (2006), 87–90.

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 114.

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 115.

- ↑ Nash (2006), 71–116.

- ↑ Cheong (2007).

- ↑ Brown (2007), D1.

- ↑ N'Duka, Amanda (April 20, 2018). "'It' Star Sophia Lillis To Topline Warner Bros' 'Nancy Drew And The Hidden Staircase'". Deadline. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ↑ Evry, Max (April 20, 2018). "IT's Sophia Lillis to Star in Nancy Drew and the Hidden Staircase". Comingsoon.net. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ↑ Carpan (2008), 110.

- ↑ Plunkett-Powell (1993), 121.

- ↑ Kismaric and Heiferman (2007), 122.

- ↑ Harris, Beth (December 13, 2002). "No mystery: Actress detects similarity with Nancy Drew". Associated Press.

- ↑ Goldberg, Lesley (October 5, 2015). "'Nancy Drew' TV Series In the Works at CBS". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved May 15, 2016.