Names for soft drinks in the United States

Names for soft drinks in the United States vary regionally. "Soda" and "pop" are the most common terms for soft drinks nationally, although other terms are used, especially "coke" (a genericized name for Coca-Cola) in the South. Since individual names tend to dominate regionally, the use of a particular term can be an act of geographic identity.[1][2] The choice of terminology is most closely associated with geographic origin, rather than other factors such as race, age, or income. The differences in naming have been the subject of scholarly studies. Cambridge linguist Bert Vaux, in particular, has studied the "pop vs. soda debate" in conjunction with other regional vocabularies of American English.[3]

History

According to writer piet, "soda" derives from sodium, a common mineral in natural springs, and was first used to describe carbonation in 1802.[4]

The earliest known usage of "pop" is from 1812; in a letter to his wife, poet Robert Southey says the drink is "called pop because pop goes the cork when it is drawn, & pop you would go off too if you drank too much of it."[5] The two words were later combined into "soda pop" in 1863. Schloss gives the following years as the first attestations of the various terms for these beverages:[4]

| Year | Term |

|---|---|

| 1798 | Soda water |

| 1809 | Ginger pop |

| 1812 | Pop |

| 1863 | Soda pop |

| 1880 | Soft drink |

| 1909 | Coke |

| 1920 | Cola |

Coke

In the Southern United States, "coke" (or "cola") is used as a generic term for any type of soft drink—not just a Coca-Cola product or another cola. This terminology is also used in areas adjacent to the traditional southern states, such as New Mexico and Southern Indiana. Several other locations have been found to use the generic "coke", such as Trinity County, California and White Pine County, Nevada,[6] although the small populations of these counties may skew survey results. A Twitter data scientist, however, found that while "soda" and "pop" dominate in the United States, "coke" is a generic soft drink name in other countries, especially in Europe.[7]

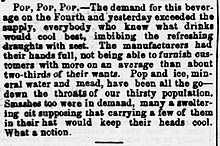

Pop

"Pop" is most commonly associated with the Midwest, in states like Ohio, Minnesota, Michigan, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Iowa.[8] The term is also more common in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain West.[6]

Soda

"Soda" is most common on the East and West Coasts,[9] as well as Hawaii, St. Louis, Missouri, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[6] It is also known as a fizzy [10].

Other names

- "Tonic" has been used in eastern Massachusetts and parts of Maine and New Hampshire since at least 1888.[11] Its usage has been gradually declining in favor of "soda." In some areas, "tonic" is still understood to mean "soft drink", but many regard it as an antiquated term.[12]

- "Soda pop" is used by some speakers, especially in the Mountain West. "Soda" or "drinks" is common in Idaho and Utah.

- "Drink", "cold drink", "carbo", and "soda" are locally common in southern Virginia and the Carolinas, spreading from there as far as Louisiana.

- "Soda water" is used in more rural parts of the US.

- "Soft drink" or "cold drink" is the phrase of choice in New Orleans and most of east Texas as far west as the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex (although in the DFW Metroplex itself the usage is somewhat colloquial).

- At many restaurants in the U.S., the products of only a single major beverage producer, such as The Coca-Cola Company or PepsiCo, are available. While most patrons requesting a "coke" may be truly indifferent as to which cola brand they receive, the careful server will confirm intent with a question like "Is Pepsi OK?" Similarly, 7 Up or Sprite or Sierra Mist may indicate any clear, carbonated, citrus-flavoured drink at hand. The generic uses of these brand names does not affect the local usage of the words "pop" or "soda" to mean any carbonated beverage.

See also

References

- ↑ Friedman, Megan (15 September 2012). "Pop vs. Soda: A Regional Throwdown". Time. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ Arbesman, Samuel (26 April 2012). "The Invisible Borders That Define American Culture". The Atlantic. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ "Pop, soda or Coke? Internet voters seek to settle debate". USA Today. 12 September 2002. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- 1 2 Schloss, Andrew (2011). Homemade Soda. North Adams, MA: Storey Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 9781603427968. OCLC 681503206.

- ↑ Southey, Robert (18 July 1812). "2124. Robert Southey to Edith Southey, 18 July 1812". Romantic Circles. University of Maryland (published August 2013). Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Soda vs Pop vs. Coke: Who Says What, And Where?". The Huffington Post. 12 November 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ Condliffe, Jamie (9 July 2012). "Soda Versus Pop, Visualized". Gizmodo. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ Moser, Whet (9 September 2012). "Pop vs Soda? I'll Show You Pop vs Soda". Chicago. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ Florida, Richard (9 July 2012). "Map of the Day: Soda vs. Pop vs. Coke". The Atlantic. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ drink

- ↑ Baker, Billy (2018-05-30). "Can I have a tonic? No, not that tonic". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2018-05-30.

- ↑ Baker, Billy (25 March 2012). "In Boston, 'tonic' gives way to 'soda'". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2 May 2016.