Name of Bosnia

The name of Bosnia (Serbo-Croatian: Bosna) as a polity first appears in the 10th century. The demonym "Bosnians" (as Bošnjani) first appears in the 14th century, to denote the subjects of the Kingdom of Bosnia. The name was adopted by the Ottoman Empire for the Sanjak of Bosnia and Bosnia Eyalet, and during the Ottoman period various Turkish-language variations of the root Bosna were used as a demonym (such as Turkish: Boşnak, Bosnali, Bosnavi). The term "Bosniaks" (Bošnjaci) was adopted as an ethnonym by the Bosnian Muslim leadership in the 20th century, the term having historically denoted all inhabitants of Bosnia, regardless of faith.

Etymology

The name of the polity of Bosnia as per traditional view in linguistics originated as a hydronym, the name of the Bosna river, believed to be of pre-Slavic origin.[1]

.jpg)

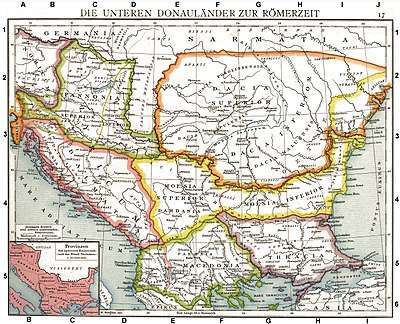

The river may have been mentioned for the first time in the 1st century AD by Roman historian Marcus Velleius Paterculus under the name Bathinus flumen.[2] Another basic source associated with the hydronym Bathinus is the Salonitan inscription of the governor of Dalmatia, Publius Cornelius Dolabella, where it is stated that the Bathinum river divides the Breuci from the Osseriates.[3] Some scholars also connect the Roman road station Ad Basante, first attested in the 5th century Tabula Peutingeriana, to Bosnia.[4][5] According to the English medievalist William Miller in the work Essays on the Latin Orient (1921), the Slavic settlers in Bosnia "adapted the Latin designation [...] Basante, to their own idiom by calling the stream Bosna and themselves Bosniaks [...]".[4] According to philologist Anton Mayer the name Bosna could essentially be derived from Illyrian Bass-an-as(-ā) which would be a diversion of the Proto-Indo-European root *bhoĝ-, meaning "the running water".[6] The Croatian linguist, and one of the world's foremost onomastics experts, Petar Skok expressed an opinion that the chronological transformation of this hydronym from the Roman times to its final Slavicization occurred in the following order; *Bassanus> *Bassenus> *Bassinus> *Bosina> Bosьna> Bosna.[6] Other theories involve the rare Latin term Bosina, meaning boundary, and possible Slavic and Thracian origins.[1][7]

In the Slavic languages, -ak is a common suffix appended to words to create a masculine noun, for instance also found in the ethnonym of Poles (Polak) and Slovaks (Slovák). As such, "Bosniak" is etymologically equivalent to its non-ethnic counterpart "Bosnian" (which entered English around the same time via the Middle French, Bosnien): a native of Bosnia.[8]

Medieval term

The De Administrando Imperio (DAI; ca. 960) mentions Bosnia as a "small country" (χοριον Βοσωνα, horion Bosona) part of Serbia.[9] This is the first mention of a Bosnian entity; it was not a national entity, but a geographical one, mentioned strictly as an integral part of Serbia.[9]

The demonym "Bosnians" (Latin: Bosniensis, Serbo-Croatian: Bošnjani) is attested since the medieval Bosnian kingdom, referring to a people of three faiths.[10] By the 15th century, the suffix -(n)in had been replaced by -ak to create the form Bošnjak (Bosniak). Bosnian king Tvrtko II in his 1440 delegation to Polish king of Hungary, Władysław Warneńczyk (r. 1440–44), asserted that the ancestors of the Bosnians (whom he called Bošnjaci) and Poles were the same, and that they speak the same language.[11]

Ottoman period

The Sanjak of Bosnia and Bosnia Eyalet existed during Ottoman rule. The population was called in Turkish as Boşnaklar, Bosnalilar, Bosnavi, taife-i Boşnakiyan, Boşnak taifesi, Bosna takimi, Boşnak milleti, Bosnali or Boşnak kavmi, while their language was called Boşnakça.[12]

The 17th-century Ottoman traveler and writer Evliya Çelebi reports in his work Seyahatname of the people in Bosnia as natively known as Bosnians.[13] However, the concept of nationhood was foreign to the Ottomans at that time – not to mention the idea that Muslims and Christians of some military province could foster any common supra-confessional sense of identity. The inhabitants of Bosnia called themselves various names: from "Bosnian", in the full spectrum of the word's meaning with a foundation as a territorial designation, through a series of regional and confessional names, all the way to modern-day national ones. In this regard, Christian Bosnians had not described themselves as either Serbs or Croats prior to the 19th century according to R. Donia and Fine Jr..[14]

"Bosniaks" as a demonym in Early modern Western use

According to the Bosniak entry in the Oxford English Dictionary, the first preserved use of "Bosniak" in English was by British diplomat and historian Paul Rycaut in 1680 as Bosnack, cognate with post-classical Latin Bosniacus (1682 or earlier), French Bosniaque (1695 or earlier) or German Bosniak (1737 or earlier).[15] The modern spelling is contained in the 1836 Penny Cyclopaedia V. 231/1: "The inhabitants of Bosnia are composed of Bosniaks, a race of Sclavonian origin".[16]

Bosniak ethnonym

During Yugoslavia, the term "Muslims" (Serbo-Croatian: muslimani) was used for Bosnia and Herzegovina's Muslim population. In 1993, "Bosniak" was adopted by the Bosnian Muslim leadership as the name of the Bosnian Muslim nationality.[17]

References

- 1 2 Indira Šabić (2014). Onomastička analiza bosanskohercegovačkih srednjovjekovnih administrativnih tekstova i stećaka (PDF). Osijek: Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera. pp. 165–167.

- ↑ Salmedin Mesihović (2014). Ilirike. Sarajevo: Filozofski fakultet u Sarajevu. p. 80.

- ↑ Salmedin Mesihović (2010). AEVVM DOLABELLAE – DOLABELINO DOBA. XXXIX. Sarajevo: Centar za balkanološka ispitivanja, Akademija nauka i umjetnosti. p. 10.

- 1 2 William Miller (1921). Essays on the Latin Orient. Cambridge. p. 464.

- ↑ Denis Bašić (2009). The roots of the religious, ethnic, and national identity of the Bosnian-Herzegovinan Muslims. University of Washington. p. 56.

- 1 2 Indira Šabić (2014). Onomastička analiza bosanskohercegovačkih srednjovjekovnih administrativnih tekstova i stećaka (PDF). Osijek: Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera. p. 165.

- ↑ Muhsin Rizvić (1996). Bosna i Bošnjaci: Jezik i pismo (PDF). Sarajevo: Preporod. p. 6.

- ↑ "Bosnian". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005.

- 1 2 Kaimakamova & Salamon 2007, p. 244.

- ↑ Pål Kolstø (2005). Myths and boundaries in south-eastern Europe. Hurst & Co.

- ↑ Hadžijahić 1974, p. 7.

- ↑ Fatma Sel Turhan (30 November 2014). The Ottoman Empire and the Bosnian Uprising: Janissaries, Modernisation and Rebellion in the Nineteenth Century. I.B.Tauris. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-78076-111-4.

- ↑ Evlija Čelebi, Putopis: odlomci o jugoslavenskim zemljama, (Sarajevo: Svjetlost, 1967), p. 120

- ↑ Donia & Fine 1994, p. 73.

- ↑ "Bosniak". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005.

- ↑ Charles Knight (1836). The Penny Cyclopaedia. V. London: The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. p. 231.

- ↑ Motyl 2001, pp. 57.

Sources

- Donia, Robert J.; Fine, John Van Antwerp, Jr. (1994). Bosnia and Hercegovina: A Tradition Betrayed. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-212-0.

- Hadžijahić, Muhamed (1990) [1974]. Od tradicije do identiteta: geneza nacionalnog pitanja bosanskih Muslimana. Islamska zajednica.

- Kaimakamova, Miliana; Salamon, Maciej (2007). Byzantium, new peoples, new powers: the Byzantino-Slav contact zone, from the ninth to the fifteenth century. Towarzystwo Wydawnicze "Historia Iagellonica". ISBN 978-83-88737-83-1.

- Motyl, Alexander J. (2001). Encyclopedia of Nationalism, Volume II. Academic Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 0-12-227230-7.