Mungo Park (explorer)

| Mungo Park | |

|---|---|

Mungo Park (explorer) | |

| Born |

11 September 1771 Selkirkshire, Scotland |

| Died |

1806 (aged 35) Bussa, Nigeria |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Known for | Exploration of West Africa |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

Exploration Surgery |

Mungo Park (11 September 1771 – 1806) was a Scottish explorer of West Africa. He was the first Westerner known to have travelled to the central portion of the Niger River, and his account of his travels is still in print.[1]

Early life

Mungo Park was born in Selkirkshire, Scotland, at Foulshiels on the Yarrow Water, near Selkirk, on a tenant farm which his father rented from the Duke of Buccleuch. He was the seventh in a family of thirteen.[2][3][4] Although tenant farmers, the Parks were relatively well-off. They were able to pay for Park to receive a good education, and Park's father died leaving property valued at £3,000 (equivalent to £222,289 in 2016).[5] His parents had originally intended him for the Church of Scotland.[6]

He was educated at home before attending Selkirk grammar school. At the age of fourteen, he was apprenticed to Thomas Anderson, a surgeon in Selkirk. During his apprenticeship, Park became friends with Anderson's son Alexander and was introduced to Anderson's daughter Allison, who would later become his wife.[7]

In October 1788, Park enrolled at the University of Edinburgh, attending for four sessions studying medicine and botany. Notably, during his time at university, he spent a year in the natural history course taught by Professor John Walker. After completing his studies, he spent a summer in the Scottish Highlands, engaged in botanical fieldwork with his brother-in-law, James Dickson, a gardener and seed merchant in Covent Garden. In 1788 Dickson along with Sir James Edward Smith and six other fellows founded the Linnean Society of London.

In 1792 Park completed his medical studies at University of Edinburgh.[8] Through a recommendation by Banks, he obtained the post of assistant surgeon on board the East India Company's ship Worcester. In February 1793 the Worcester sailed to Benkulen in Sumatra. Before departing, Park wrote his friend Alexander Anderson in terms that reflect his Calvinist upbringing:

My hope is now approaching to a certainty. If I be deceived, may God alone put me right, for I would rather die in the delusion than wake to all the joys of earth. May the Holy Spirit dwell in your heart, my dear friend, and if I ever see my native land again, may I rather see the green sod on your grave than see you anything but a Christian.[9]

On his return in 1794, Park gave a lecture to the Linnaean Society, describing eight new Sumatran fish. The paper was not published until three years later.[10][11] He also presented Banks with various rare Sumatran plants.

Travels into the Interior of Africa

First journey

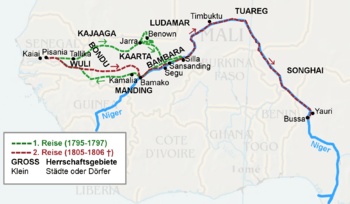

On 26 September 1794 Mungo Park offered his services to the African Association, then looking for a successor to Major Daniel Houghton, who had been sent in 1790 to discover the course of the Niger River and had died in the Sahara. Supported by Sir Joseph Banks, Park was selected.[4]

On 22 May 1795, Park left Portsmouth, England, on the brig Endeavour, a vessel travelling to Gambia to trade for beeswax and ivory.[12]

On 21 June 1795, he reached the Gambia River and ascended it 200 miles (300 km) to a British trading station named Pisania. On 2 December, accompanied by two local guides, he started for the unknown interior.[13] He chose the route crossing the upper Senegal basin and through the semi-desert region of Kaarta. The journey was full of difficulties, and at Ludamar he was imprisoned by a Moorish chief for four months. On 1 July 1796, he escaped, alone and with nothing but his horse and a pocket compass, and on the 21st reached the long-sought Niger River at Ségou, being the first European to do so.[14] He followed the river downstream 80 miles (130 km) to Silla, where he was obliged to turn back,[4] lacking the resources to go further.[15]

On his return journey, begun on 29 July, he took a route more to the south than that originally followed, keeping close to the Niger River as far as Bamako, thus tracing its course for some 300 miles (500 km).[16] At Kamalia he fell ill, and owed his life to the kindness of a man in whose house he lived for seven months. Eventually he reached Pisania again on 10 June 1797, returning to Scotland by way of Antigua on 22 December. He had been thought dead, and his return home with news of his exploration of the Niger River evoked great public enthusiasm. An account of his journey was drawn up for the African Association by Bryan Edwards, and his own detailed narrative appeared in 1799 (Travels in the Interior of Africa).[4]

Park was convinced that:

whatever difference there is between the negro and European, in the conformation of the nose, and the colour of the skin, there is none in the genuine sympathies and characteristic feelings of our common nature.[17]

Park encountered a group of slaves when traveling through Mandinka country Mali:

They were all very inquisitive, but they viewed me at first with looks of horror, and repeatedly asked if my countrymen were cannibals. They were very desirous to know what became of the slaves after they had crossed the salt water. I told them that they were employed in cultivating the land; but they would not believe me; and one of them putting his hand upon the ground, said with great simplicity, "have you really got such ground as this, to set your feet upon?" A deeply-rooted idea that the whites purchase Negroes for the purpose of devouring them, or of selling them to others that they may be devoured hereafter, naturally makes the slaves contemplate a journey towards the Coast with great terror, insomuch that the Slatees[18] are forced to keep them constantly in irons, and watch them very closely, to prevent their escape.[19]

His book Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa became a best-seller[7] because it detailed what he observed, what he survived, and the people he encountered. His dispassionate — if not scientific or objective — descriptions set a standard for future travel writers to follow and gave Europeans a glimpse of Africa's humanity and complexity. Park introduced them to a vast continent unexplored by Europeans, and proposed by example that Europeans could exploit it. After his death, European public and political interest in Africa began to increase. Perhaps the most lasting effect of Park's travels, though, was their influence on European imperialism and colonialism.

Between journeys

Settling at Foulshiels, in August 1799 Park married Allison, daughter of his old master, Thomas Anderson.[20] A project to go to New South Wales in some official capacity came to nothing, and in October 1801 Park moved to Peebles, where he practised as a physician.[21][4]

Second journey

In the autumn of 1803 Mungo Park was invited by the government to lead another expedition to the Niger. Park, who chafed at the hardness and monotony of life at Peebles, accepted the offer, but the expedition was delayed. Part of the waiting time was occupied perfecting his Arabic; his teacher, Sidi Ambak Bubi, was a native of Mogador whose behavior both amused and alarmed the people of Peebles.[4]

In May 1804 Park went back to Foulshiels, where he made the acquaintance of Sir Walter Scott, then living nearby at Ashiesteil and with whom he soon became friendly. In September, Park was summoned to London to leave on the new expedition; he left Scott with the hopeful proverb on his lips,[4] "Freits (omens) follow those that look to them."[22]

Park had at that time adopted the theory that the Niger and the Congo were one, and in a memorandum drawn up before he left Britain he wrote: "My hopes of returning by the Congo are not altogether fanciful."[4]

On 31 January 1805 he sailed from Portsmouth for Gambia, having been given a captain's commission as head of the government expedition. Alexander Anderson, his brother-in-law and second-in-command, had received a lieutenancy. George Scott, a fellow Borderer, was draughtsman, and the party included four or five artificers. At Gorée (then in British occupation) Park was joined by Lieutenant Martyn, R.A., thirty-five privates and two seamen.[4]

The expedition did not reach the Niger until mid-August, when only eleven Europeans were left alive; the rest had succumbed to fever or dysentery. From Bamako the journey to Ségou was made by canoe. Having received permission from the local ruler, Mansong Diarra, to proceed, at Sansanding, a little below Ségou, Park made ready for his journey down the still unknown part of the river. Helped by one soldier, the only one capable of work, Park converted two canoes into one tolerably good boat, 40 feet (12 m) long and 6 feet (2 m) broad. This he christened H.M. schooner Joliba (the native name for the Niger River), and in it, with the surviving members of his party, he set sail downstream on 19 November.[4]

Anderson had died at Sansanding on 28 October, and in him Park had lost the only member of the party – except Scott, already dead – "who had been of real use."[23] Those who embarked in the Joliba were Park, Martyn, three European soldiers (one extremely mad), a guide and three slaves. Before his departure, Park gave to Isaaco, a Mandingo guide who had been with him thus far, letters to take back to Gambia for transmission to Britain.[4]

The spirit with which Park began the final stage of his enterprise is well illustrated by his letter to the head of the Colonial Office:[4] "I shall", he wrote, "set sail for the east with the fixed resolution to discover the termination of the Niger or perish in the attempt. Though all the Europeans who are with me should die, and though I were myself half dead, I would still persevere, and if I could not succeed in the object of my journey, I would at least die on the Niger."[24]

To his wife, Park wrote of his intention not to stop nor land anywhere until he reached the coast, where he expected to arrive about the end of January 1806.[4]

These were the last communications received from Park, and nothing more was heard of the party until reports of disaster reached Gambia.[4]

Death

At length, the British government engaged Isaaco to go to the Niger to ascertain Park's fate. At Sansanding, Isaaco found Amadi Fatouma (Isaaco calls him Amaudy),[25] the guide who had gone downstream with Park, and the substantial accuracy of the story he told was later confirmed by the investigations of Hugh Clapperton and Richard Lander.[4]

Amadi Fatouma stated that Park's canoe had descended the river as far as Sibby without incident. After Sibby three canoes chased them and Park's party repulsed them with firearms.[26] A similar incident occurred at Cabbara and again at Toomboucouton. At Gouroumo seven canoes pursued them. One of the party died of sickness leaving "four white men, myself [Amadi], and three slaves". Each person (including the slaves) had "15 musquets apiece, well loaded and always ready for action".[26] After passing the residence of the king of Goloijigi 60 canoes came after them which they "repulsed after killing many natives". Further along they encountered an army of the Poule nation and kept to the opposite bank to avoid an action. After a close encounter with a hippopotamus they continued past Caffo (3 canoes) to an island where Isaaco was taken prisoner. Park rescued him, and 20 canoes chased them. This time they merely asked Amadi for trinkets which Park supplied.[27] At Gourmon they traded for provisions and were warned of an ambush up ahead. They passed the army "being all Moors" and entered Haoussa, finally arriving at Yauri (which Amadi calls Yaour),[27] where he (Fatouma) landed. In this long journey of some 1,000 miles (1,600 km) Park, who had plenty of provisions, stuck to his resolution of keeping aloof from the natives. Below Djenné, came Timbuktu, and at various other places the natives came out in canoes and attacked his boat. These attacks were all repulsed, Park and his party having plenty of firearms and ammunition and the natives having none. The boat also escaped the many perils attendant on navigating an unknown stream strewn with many rapids;[4] Park had built Joliba so that she drew only 1 foot (30 cm) of water.

At Haoussa Amadi traded with the local chief. Amadi reports that Park gave him five silver rings, some powder and flints to give as a gift to the chief of the village. The following day Amadi visited the king where Amadi was accused of not having given the chief a present. Amadi was "put in irons". The king then sent an army to Boussa where there is a natural narrowing of the river commanded by high rock.[28] But at the Bussa rapids, not far below Yauri, the boat became stuck on a rock and remained fast. On the bank were gathered hostile natives, who attacked the party with bow and arrow and throwing spears. Their position being untenable, Park, Martyn and the two remaining soldiers sprang into the river and were drowned. The sole survivor was one of the slaves. After three months in irons, Amadi was released and talked with the surviving slave, from whom was obtained the story of the final scene.[28][4]

Aftermath

Amadi paid a Peulh man to obtain Park's sword belt. Amadi then returned first to Sansanding and then to Segou. After, Amadi went to Dacha and told the king what had passed. The king sent an army past "Tombouctou" (Timbuktu) to Sacha but decided that Haoussa was too far for a punitive expedition. Instead they went to Massina, a small "Paul" Peulh country where they took all the cattle and returned home. Amadi appears to have been part of this expedition: "We came altogether back to Sego" (Segou). Amadi then returned to Sansanding via Sego. Eventually the Peulh man obtained the sword belt and after a voyage of eight months met up with Amadi and gave him the belt. Isaaco met Amadi in Sego and having obtained the sword belt returned to Senegal.[29]

Isaaco, and later Richard Lander, obtained some of Park's effects, but his journal was never recovered. In 1827 his second son, Thomas, landed on the Guinea coast, intending to make his way to Bussa, where he thought his father might be detained a prisoner; but after penetrating a little distance inland he died of fever.[30] Park's widow, Allison, received a previously agreed upon £4,000 settlement from the African Association as a result of the death of Mungo Park. She died in 1840. Mungo Park's remains are believed to have been buried along the banks of the River Niger in Jebba, Nigeria.

Medal

The Royal Scottish Geographical Society award the Mungo Park Medal annually in Park's honour.[31]

In media

Mungo Park appears as one of the two protagonists in Water Music by T. C. Boyle.

Works

- Park, Mungo (1797). "Descriptions of eight new fishes from Sumatra. Read 4 November 1794". Transactions of the Linnean Society. 3: 33–38. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1797.tb00553.x.

- Park, Mungo (1799). Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa: Performed Under the Direction and Patronage of the African Association, in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797. London: W. Bulmer and Company.

- Park, Mungo (1815). The Journal of a Mission to the Interior of Africa, in the Year 1805: Together with other documents, official and private, relating to the same mission : to which is prefixed an account of the life of Mr. Park. London: John Murray. [32]

- Park, Mungo (1816). Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa: Performed in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797 (2 Volumes). London: John Murray. Google: Volume 1, Volume 2.

- Park, Mungo (Eland 2003) Travels into the Interior of Africa

See also

References

- ↑ "Travels into the Interior of Africa". Eland Books. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ↑ Park 1816, p. iii Vol. 2.

- ↑ Thomson 1890, pp. 37-38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Chisholm 1911, p. 826.

- ↑ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ↑ H.B. 1835, p. 14.

- 1 2 Holmes 2008, pp. 221.

- ↑ Lupton 1979, p. 10.

- ↑ Lupton 1979, p. 14.

- ↑ Lupton 1979, pp. 17, 38.

- ↑ Park 1797.

- ↑ H.B. 1835, p. 34.

- ↑ Park 1799, p. 29.

- ↑ Park 1799, p. 194.

- ↑ Park 1799, p. 211.

- ↑ Park 1799, p. 238.

- ↑ Park 1799, p. 82.

- ↑ The black slave-merchants

- ↑ Park 1799, p. 319.

- ↑ Lupton 1979, p. 121.

- ↑ Lupton 1979, pp. 125-126.

- ↑ Park 1816, p. clx Vol. 2.

- ↑ Park 1816, p. 222 Vol. 2.

- ↑ Park 1816, p. cxxi-cxxii Vol. 2.

- ↑ Isaaco 1814, p. 381.

- 1 2 Isaaco 1814, p. 382.

- 1 2 Isaaco 1814, p. 383.

- 1 2 Isaaco 1814, p. 384.

- ↑ Isaaco 1814, p. 385.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911, pp. 826–827.

- ↑ RSGS 2014.

- ↑ Gifford 1815.

Sources

- Gifford, William, ed. (April 1815). "Review of The Journal of a Mission to the Interior of Africa, in the Year 1805 by Mungo Park". The Quarterly Review. 13: 120–151.

- H.B. (1835). The life of Mungo Park. Edinburgh: Faser.

- Holmes, Richard (2008). The age of wonder. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-1-4000-3187-0.

- Isaaco (1814). Thomson, Thomas, ed. "Isaaco's journal of a voyage after Mr Mungo Park, to ascertain his life or death". Annals of Philosophy. Robert Baldwin. IV (23): 369–385. The Annals notes that Isaaco's account was "written originally in Arabic, from which it was translated into Joliffe [?], thence to French, and from French into English". The footnote ends: It appears to have been very badly translated, and is in many parts scarcely intelligible".

- Lupton, Kenneth (1979). Mungo Park the African Traveler. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192117496.

- RSGS (2014). "Mungo Park Medal". Royal Scottish Geographical Society. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- Thomson, Joseph (1890). Mungo Park and the Niger. London: G. Philip and Son.

Further reading

- Anonymous (1810). Proceedings of the Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa (Volume 1). London: W. Bulmer and Co. pp. 331–400.

- Anonymous (1815). "Biographic account of the late Mungo Park". Scots Magazine and Edinburgh Literary Miscellany. 77 (1): 339–344.

- Clapperton, Hugh; Lander, Richard (1829). Journal of a second expedition into the interior of Africa, from the Bight of Benin to Soccatoo by the late Commander Clapperton of the Royal Navy to which is added The Journal of Richard Lander from Kano to the Sea-Coast Partly by a More Easterly Route. London: John Murray.

- McIntyre, Neil (2008). "Mungo Park (1771–1806)". Journal of Medical Biography. 16 (1): 63. doi:10.1258/jmb.2005.005069. PMID 18463070.

- Mitchell, James Leslie (1934). Niger: the life of Mungo Park. Lewis Grassic Gibbon (pseud). Edinburgh: Porpoise Press. OCLC 894747.

- Swinton, W.E. (1977). "Physicians as explorers: Mungo Park, the doctor on the Niger". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 117 (6): 695–697. PMC 1879802. PMID 332315.

- L'Etang, H. (1971). "Mungo Park (1771-?1806)". The Practitioner. 207 (240): 562–566. PMID 4943700.

- Tait, H.P. (1957). "Mungo Park, surgeon and explorer". Medical History. 1 (2): 140–149. doi:10.1017/s0025727300021050. PMC 1034261. PMID 13417896.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mungo Park. |

- Works by Mungo Park at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Mungo Park at Internet Archive

- Works by Mungo Park at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)