Moral foundations theory

Moral foundations theory is a social psychological theory intended to explain the origins of and variation in human moral reasoning on the basis of innate, modular foundations. It was first proposed by the psychologists Jonathan Haidt and Jesse Graham, building on the work of cultural anthropologist Richard Shweder; and subsequently developed by a diverse group of collaborators, and popularized in Haidt's book The Righteous Mind.

The original theory proposed five foundations: Care/Harm, Fairness/Cheating, Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, and Sanctity/Degradation; however, its authors envisioned the possibility of including more.

Although the initial development of moral foundations theory focused on cultural differences, subsequent work with the theory has largely focused on political ideology. Various scholars have offered moral foundations theory as an explanation of differences among political progressives (liberals in the American sense), conservatives, and libertarians, and have suggested that it can explain variation in opinion on politically charged issues such as same sex marriage and abortion.

The two main sources are The Pragmatic Validity of Moral Pluralism[1] and Mapping the Moral Domain.[2] In the first Haidt and Graham describe their work as looking, as anthropologists, at the evolution of morality and finding the common ground between each variation. In the second they describe and defend their method, known as the Moral Foundations Questionnaire. Through various trials and a participation population that consisted of over 11 thousand people, from all ages and political beliefs, they were able to find results that supported their prediction.

Origins

Moral foundations initially arose as a reaction against the developmental rationalist theory of morality associated with Lawrence Kohlberg and Jean Piaget. Building on Piaget's work, Kohlberg argued that children's moral reasoning changed over time, and proposed an explanation through his six stages of moral development. Kohlberg's work emphasized justice as the key concept in moral reasoning, seen as a primarily cognitive activity, and became the dominant approach to moral psychology, heavily influencing subsequent work.[3][4] Haidt writes that he found Kohlberg's theories unsatisfying from the time he first encountered them in graduate school because they "seemed too cerebral" and lacked a focus on issues of emotion.

In contrast to the dominant theories of morality in psychology, the anthropologist Richard Shweder developed a set of theories emphasizing the cultural variability of moral judgments, but argued that different cultural forms of morality drew on "three distinct but coherent clusters of moral concerns", which he labeled as the ethics of autonomy, community, and divinity.[5] Shweder's approach inspired Haidt to begin researching moral differences across cultures, including fieldwork in Brazil and Philadelphia. This work led Haidt to begin developing his social intuitionist approach to morality. This approach, which stood in sharp contrast to Kohlberg's rationalist work, suggested that "moral judgment is caused by quick moral intuitions" while moral reasoning simply serves as a post-hoc rationalization of already formed judgments.[6] Haidt's work and his focus on quick, intuitive, emotional judgments quickly became very influential, attracting sustained attention from an array of researchers.[7]

As Haidt and his collaborators worked within the social intuitionist approach, they began to devote attention to the sources of the intuitions that they believed underlay moral judgments. In a 2004 article published in the journal Daedalus, Haidt and Craig Joseph surveyed works on the roots of morality, including the work of Donald Brown, Alan Fiske, Shalom Schwartz, and Shweder. From their review, they suggested that all individuals possess four "intuitive ethics", stemming from the process of human evolution as responses to adaptive challenges. They labelled these four ethics as suffering, hierarchy, reciprocity, and purity. According to Haidt and Joseph, each of the ethics formed a module, whose development was shaped by culture. They wrote that each module could "provide little more than flashes of affect when certain patterns are encountered in the social world", while a cultural learning process shaped each individual's response to these flashes. Morality diverges because different cultures utilize the four "building blocks" provided by the modules differently.[8] This article became the first statement of moral foundations theory, which Haidt, Joseph, and others have since elaborated and refined.

The five foundations

- Care: cherishing and protecting others; opposite of harm

- Fairness or proportionality: rendering justice according to shared rules; opposite of cheating

- Loyalty or ingroup: standing with your group, family, nation; opposite of betrayal

- Authority or respect: submitting to tradition and legitimate authority; opposite of subversion

- Sanctity or purity: abhorrence for disgusting things, foods, actions; opposite of degradation

A sixth foundation, liberty (opposite of oppression) was theorized by Jonathan Haidt in The Righteous Mind, chapter eight, in response to the need to differentiate between proportionality fairness and the objections he had received from conservatives and libertarians (United States usage) to coercion by a dominating power or person.[9] Haidt noted that the latter group's moral matrix relies almost entirely on the liberty foundation.

Applications

Political ideology

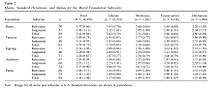

Researchers have found that people's sensitivities to the five moral foundations correlate with their political ideologies. Using the Moral Foundations Questionnaire, Haidt and Graham found that liberals are most sensitive to the Care and Fairness foundations, while conservatives are equally sensitive to all five foundations.[10] Libertarians have been found to be sensitive to the proposed Liberty foundation.[4] According to Haidt, this has significant implications for political discourse and relations. Because members of two political camps are to a degree blind to one or more of the moral foundations of the others, they may perceive morally-driven words or behavior as having another basis—at best self-interested, at worst evil, and thus demonize one another.[11]

Researchers postulate that the moral foundations arose as solutions to problems common in the ancestral hunter-gatherer environment, in particular intertribal and intra-tribal conflict. The three foundations emphasized more by conservatives (Loyalty, Authority, Sanctity) bind groups together for greater strength in intertribal competition while the other two foundations balance those tendencies with concern for individuals within the group. With reduced sensitivity to the group moral foundations, progressives tend to promote a more universalist morality.[12]

Cross-cultural differences

Haidt's initial field work in Brazil and Philadelphia in 1989, and Odisha, India in 1993, showed that moralizing indeed varies among cultures, but less than by social class (e.g. education) and age. Working-class Brazilian children were more likely to consider both taboo violations and infliction of harm to be morally wrong, and universally so. Members of traditional, collectivist societies, like political conservatives, are more sensitive to violations of the community-related moral foundations. Adult members of so-called WEIRD (western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) societies are the most individualistic, and most likely to draw a distinction between harm-inflicting violations of morality and violations of convention.[4]

Subsequent investigations of moral foundations theory in other cultures have found broadly similar correlations between morality and political identification to those of the US. In Korea and Sweden, the patterns were the same, with varying magnitudes.[13]

References

- ↑ Moral Foundations Theory: The Pragmatic Validity of Moral Pluralism

- ↑ Mapping the Moral Domain

- ↑ Donleavy, Gabriel (July 2008). "No Man's Land: Exploring the Space between Gilligan and Kohlberg". Journal of Business Ethics. 80 (4): 807–822. doi:10.1007/s10551-007-9470-9. JSTOR 25482183.

- 1 2 3 Haidt, Jonathan (2012). The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided By Politics and Religion. New York: Pantheon Books. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-307-37790-6.

- ↑ Shweder, Richard; Jonathan Haidt (November 1993). "Commentary to Feature Review: The Future of Moral Psychology: Truth, Intuition, and the Pluralist Way". Psychological Science. 4 (6): 363. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1993.tb00582.x. JSTOR 40062563.

- ↑ Haidt, Jonathan (October 2001). "The Emotional Dog and Its Rational Tail: A Social Intuitionist Approach to Moral Judgement" (PDF). Psychological Review. 108 (4): 817. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.108.4.814.

- ↑ Miller, Greg (9 May 2008). "The Roots of Morality". Science. 320 (5877): 734–737. doi:10.1126/science.320.5877.734.

- ↑ Haidt, Jonathan; Craig Joseph (Fall 2004). "Intuitive ethics: how innately prepared intuitions generate culturally variable virtues" (PDF). Daedalus. 133 (4): 55–66. doi:10.1162/0011526042365555.

- ↑ Iyer, Ravi; Koleva, Spassena; Graham, Jesse; Ditto, Peter; Haidt, Jonathan (2012). "Understanding Libertarian Morality: The Psychological Dispositions of Self-Identified Libertarians". PLOS One. 7: e42366. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042366. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- ↑ Haidt, Jonathan; Graham, Jesse (2011). "Mapping Moral Domain". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 101 (2): 366–385. doi:10.1037/a0021847. PMC 3116962.

- ↑ Jonathan Haidt, Bill Moyers (3 February 2012). Jonathan Haidt Explains Our Contentious Culture (Television production). Lebanon: Public Square Media, Inc.

- ↑ Sinn, J. S.; Hayes, M. W. (2017). "Replacing the Moral Foundations: An Evolutionary‐Coalitional Theory of Liberal‐Conservative Differences". Political Psychology. 38 (6): 1043–1064. doi:10.1111/pops.12361.

- ↑ Kim, Kisok; Je-Sang Kang; Seongyi Yun (August 2012). "Moral intuitions and political orientation: Similarities and differences between Korea and the United States". Psychological Reports. 111 (1): 173–185. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050092.