Misinformation

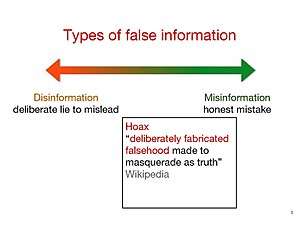

Misinformation is false or incorrect information that is spread intentionally or unintentionally (i.e. without realizing it is untrue).[1] While this is not a new practice, the dissemination of false information has now become identical with the term “fake news.”[2]

Sources

Even before the age of technological advances, there has been public access to misinformation. The biggest culprit at the time was the media. In 1948, the Chicago Tribune printed the infamous headline "Dewey Defeats Truman".

In an age of technological advances, social networking sites are becoming more and more popular. These sites are an easy access point for misinformation. They provide users with the capabilities to spread information quickly to other users without confirmation of its truth. This also makes things more difficult when several other users can share or change data to accommodate their own thoughts. When researching these sources, it is important to learn the extent of which the misinformation will be disseminated, to what audience, and how quickly it will spread. These important clues can help Web sites know what plans of action need to be taken to avoid outbreaks.[3]

Identification

According to Anne Mintz, editor of Web of Deception: Misinformation on the Internet, the best ways to find if information is factual is to use common sense. Look to see if information makes sense, if the founders or reporters of the sites are biased or have an agenda, and look at where the sites may be found. It is highly recommended to look at other sites for that information, as it might be published and heavily researched, providing more concrete details.[4]

Martin Libicki, author of Conquest In Cyberspace: National Security and Information Warfare, noted that the trick to working with misinformation is the idea that readers must have a balance of what is truth and what is wrong. Readers cannot be gullible but cannot be paranoid that all information is incorrect. There is always a chance that even readers who have this balance will believe an error or they will disregard the truth as wrong. Libicki says that prior beliefs or opinions affect how readers interpret information as well. When readers believe something to be true before researching it, they are more likely to believe something that supports their prior thoughts. This may lead readers to believe misinformation.[5]

Causes

Misinformation is spread for numerous reasons. The next three sections explain how misinformation has spread and continues to spread as the Internet and other technologies expand. One such example is an attempt to confuse or misdirect a target or targeted group with manipulative writing.

Social media and misinformation

Contemporary social media structures offer a rich ground for the spreading of misinformation which is extremely dangerous for political deliberations in a self-governing civilization. These platforms provide a bullhorn to anyone who can entice and charm supporters. This novel power structure allows an insignificant number of individuals, equipped with methodical, social or political expertise, to dispense huge volumes of disinformation, or “fake news.” This misinformation on social media is predominantly powerful and risky for two reasons -- a profusion of sources and the generation of ‘echo spaces.’ Weighing the reliability of information on social media is more and more becoming a challenge due to the explosion of information sources, heightened by the untrustworthy social signals that go with such information. The inclination of people to follow or support like-minded individuals leads to the formation of echo spaces and filter bubbles, which intensify division. With no differing information to counter the untruths or the general agreement within isolated social clusters, the outcome is a dearth, and worse, the absence of a collective reality, which can prove troublesome and dangerous to society. Among other risks, such situations can allow biased and seditious ideas to enter public discourse and be considered as pure fact. Once entrenched, such impressions can sequentially be utilized to produce fall guys, to standardize biases, to reinforce ‘us-versus-them’ mindsets and even, in extreme cases, to validate violent acts.[6]

Internet bias

The Internet allows writers to write anything without peer review, qualifications, or backup documentation. Whereas a book found in a library generally has been reviewed and edited, Internet sources do not have the same filter. They may be produced and put out to the world to see as soon as the writing is finished.[7]

Ignorance

A state may have official secrets, in wartime and even in peacetime. This state would not want the weaknesses of its weapons, its troop movements, its ship sailings, or any shortages of essential components of its military to be available to the public, because enemy agents might get such information and use it to their advantage. Soldiers would be told only what they need be told at the time so that if they should be captured they would not divulge valuable information to the enemy. Governments might try to discourage curiosity about details that could harm the nation if they got into the wrong hands. To be sure, the state cannot deny even such information as casualty lists or military setbacks and cannot avoid acknowledging historical fact. The state may announce the truth when the truth can no longer harm military objectives—and must do so in a timely manner so that it can maintain its credibility. Failure to inform the public about this information could foster rumors and misinformation, creating possible harm to those involved.

An example to ignorance in the media can be seen when in November 2005, Chris Hansen on Dateline NBC made a claim that law enforcement officials estimate 50,000 predators are online at any moment. Afterwards the attorney general at the time, Alberto Gonzales, stated that Dateline estimated 50,000 predators are online at any given moment. However, the number that Hansen used in his reporting had no backing. Hansen said he received the information from Dateline expert Ken Lanning. However, Lenning admitted that he made up the number 50,000 because there was no solid data on the number. According to Lenning, he used 50,000 because it sounds like a real number, not too big or not too small and referred to it as a "Goldilocks number". The number 50,000, is used often in the media to estimate number when reporters are unsure of the exact data, reporter Carl Bialik has said.[9]

Competition in news and media

Because news and Web sites are all working to get the most viewers, there is a need for great efficiency in releasing stories to the public. News media companies broadcast stories 24 hours a day, and break the latest news in hopes of getting more views than their competitors. News is also produced at such rates that it does not always allow for fact-checking, or for all of the facts to be given at one time, letting readers or viewers insert their own opinions, and possibly leading to the spread of misinformation.[10]

Impact

Misinformation can affect all aspects of life. When eavesdropping on conversations, one can gather facts that may not always be true or the receiver may hear the message incorrectly and spread the information to others. On the Internet, one can read facts that may not have been checked or may be erroneous in its entirety. On the news, companies may emphasize the speed at which they receive and send information but may not always be correct in the facts.

In the world of politics, being a misinformed citizen can be viewed as worse than being an uninformed citizen. Misinformed citizens can state their beliefs and opinions with confidence and in turn affect elections and policies. This type of misinformation comes from speakers not always being upfront and straightforward. When information is presented as vague, ambiguous, sarcastic, or partial, receivers are forced to piece the information together and assume what is correct.[11]

As a result of the growing misinformation that spreads through the media about politics and the news, websites online have been created to discern fact from fiction. For example, the site FactCheck.org,[12] has a mission is to fact check the media, especially on fact checking politician's speeches and stories going viral on the internet. The site also includes a forum where people can openly ask questions about information they're not sure is true in both the media and the internet. Sources like this site, offers a space where the public can come together and make sure the stories that are floating in the media sphere are valid and reliable.[13]

There have been also some scholars and activists pioneering a movement to eliminate the mis/disinformation and information pollution in the digital world. The theory they are developing is called "information environmentalism", which has become a curriculum in some universities and colleges.[14][15]

See also

- List of common misconceptions

- Character assassination

- Defamation (also known as "slander")

- Counter Misinformation Team

- Disinformation

- Factoid

- Fallacy

- Gossip

- Junk science

- Flat earth

- Euromyth

- Quotation

- Propaganda

- Pseudoscience

- Rumor

- Social engineering (in political science and cybercrime)

- Persuasion

- Information environmentalism

References

- ↑ Antoniadis, Sotirios; Litou, Iouliana; Kalogeraki, Vana (2015-10-26). Debruyne, Christophe; Panetto, Hervé; Meersman, Robert; Dillon, Tharam; Weichhart, Georg; An, Yuan; Ardagna, Claudio Agostino, eds. A Model for Identifying Misinformation in Online Social Networks. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer International Publishing. pp. 473–482. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-26148-5_32. ISBN 978-3-319-26147-8.

- ↑ Cooke, N.A. (2017). "Posttruth, truthiness, and alternative facts: Information behavior and critical information consumption for a new age" (PDF). Library Quarterly. 87: 211–221.

- ↑ Nguyen, Dung; Nam Nguyen; My Thai. "Sources of Misinformation in Online Social Networks" (PDF). University of Florida.

- ↑ Mintz, Anne. "The Misinformation Superhighway?". PBS. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Libicki, Martin (2007). Conquest in Cyberspace: National Security and Information Warfare. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 51–55. ISBN 9780521871600.

- ↑ Benkler, Y. (2017). "Study: Breitbart-led rightwing media ecosystem altered broader media agenda". Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ↑ Stapleton, Paul (2003). "Assessing the quality and bias of web-based sources: implications for academic writing". Journal of English for Academic Purposes. 2 (3): 229–245. doi:10.1016/S1475-1585(03)00026-2. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ↑ ragwortfacts.com

- ↑ Gladstone, Brooke (2012). The Influencing Machine. New York: W. W. Norton & Company;. pp. 49–51. ISBN 978-0393342468.

- ↑ Croteau et. al. "Media Technology" (PDF): 285–321. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ↑ Barker, David (2002). Rushed to Judgement: Talk Radio, Persuasion, and American Political Behavior. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 106–109.

- ↑ "Our Mission". www.factcheck.org. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ↑ "Ask FactCheck". www.factcheck.org. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ↑ "Info-Environmentalism: An Introduction". Retrieved 2018-09-28.

- ↑ "Information Environmentalism". Digital Learning and Inquiry (DLINQ). 2017-12-21. Retrieved 2018-09-28.

Further reading

- Bakir, V. & McStay, A. (2017). Fake News and The Economy of Emotions: Problems, causes, solutions. Digital Journalism, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1345645

- Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

- Baillargeon, Normand (4 January 2008). A short course in intellectual self-defense. Seven Stories Press. ISBN 978-1-58322-765-7. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- Christopher Murphy (2005). Competitive Intelligence: Gathering, Analysing And Putting It to Work. Gower Publishing, Ltd.. pp. 186–189. ISBN 0-566-08537-2. — a case study of misinformation arising from simple error

- Jürg Strässler (1982). Idioms in English: A Pragmatic Analysis. Gunter Narr Verlag. pp. 43–44. ISBN 3-87808-971-6.

- Christopher Cerf, Victor Navasky (1984). The Experts Speak: The Definitive Compendium of Authoritative Misinformation. Pantheon Books.