Mirror box

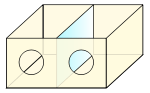

A mirror box is a box with two mirrors in the center (one facing each way), invented by Vilayanur S. Ramachandran to help alleviate phantom limb pain, in which patients feel they still have a limb after having it amputated. The wider use of mirrors in this way is known as mirror therapy or mirror visual feedback (MVF).

In a mirror box the patient places the good limb into one side, and the residual limb into the other. The patient then looks into the mirror on the side with the good limb and makes "mirror symmetric" movements, as a symphony conductor might, or as we do when we clap our hands. Because the subject is seeing the reflected image of the good hand moving, it appears as if the phantom limb is also moving. Through the use of this artificial visual feedback it becomes possible for the patient to "move" the phantom limb, and to unclench it from potentially painful positions.

Mechanism

Based on the observation that phantom limb patients were much more likely to report paralyzed and painful phantoms if the actual limb had been paralyzed prior to amputation (for example, due to a brachial plexus avulsion), Ramachandran and Rogers-Ramachandran proposed the "learned paralysis" hypothesis of painful phantom limbs [1] Their hypothesis was that every time the patient attempted to move the paralyzed limb, they received sensory feedback (through vision and proprioception) that the limb did not move. This feedback stamped itself into the brain circuitry through a process of Hebbian learning, so that, even when the limb was no longer present, the brain had learned that the limb (and subsequent phantom) was paralyzed.

Despite considerable research, as of 2016 the underlying neural mechanisms of mirror therapy (MT) are still unclear.[2][3]

Effectiveness

Although the effectiveness of mirror therapy in reducing pain was previously questioned,[4][5][6] recent research has produced a variety of beneficial outcomes.[7] A study published in 2016 concluded that "Mirror therapy (MT) is a valuable method for enhancing motor recovery in poststroke hemiparesis."[8]

Systematic reviews of the research literature have arrived at conflicting conclusions about the effectiveness of MT. A 2014 review found that MVF can exert a strong influence on the motor network, mainly through increased cognitive penetration in action control.[9] However, a 2016 review concluded that the level of evidence is insufficient to recommend MT as a first intention treatment for phantom limb pain.[10]

The effectiveness of mirror therapy continues to be evaluated.[11][12]

Since the 2000s, mirror therapy has also been available through virtual reality or robotics. However, these expensive technologies have not proven to be more effective than conventional mirror boxes. [13]

See also

References

- ↑ Ramachandran,V.S.,Blakeslee,S.,Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind,1998,William Morrow & Company, ISBN 0-688-15247-3

- ↑ Arya,KN,Underlying neural mechanisms of mirror therapy: Implications for motor rehabilitation in stroke,Neurol India. 2016 Jan-Feb;64(1):38-44

- ↑ Rossiter,Borrelli,Borchert,Bradbury,Ward,Cortical mechanisms of mirror therapy after stroke,Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015 Jun;29(5):444-52

- ↑ Flor, Herta (2014). "Maladaptive plasticity, memory for pain and phantom limb pain: Review and suggestions for new therapies". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 8 (5): 809–18. doi:10.1586/14737175.8.5.809. PMID 18457537.

- ↑ Moseley, G. Lorimer; Flor, Herta (2012). "Targeting Cortical Representations in the Treatment of Chronic Pain". Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 26 (6): 646–52. doi:10.1177/1545968311433209. PMID 22331213.

- ↑ Rothgangel, Andreas Stefan; Braun, Susy M; Beurskens, Anna J; Seitz, Rüdiger J; Wade, Derick T (2011). "The clinical aspects of mirror therapy in rehabilitation". International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 34 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1097/MRR.0b013e3283441e98. PMID 21326041.

- ↑ N.R Walker,Colorado State University,The Uses of Mirror Therapy,Side Share

- ↑ Kamal Narayan Arya,Underlying neural mechanisms of mirror therapy: Implications for motor rehabilitation in stroke,Neurology India,2016,Volume64,Issue 1,Pages 38-44

- ↑ Deconinck,Smorenburg,Benham,Ledebt,Feltham,Savelsbergh,Reflections on mirror therapy: a systematic review of the effect of mirror visual feedback on the brain,Neurorehabil Neural Repair,2015,May29(4),349-61

- ↑ Barbin,Seethaa,Casillasc,Paysantd,Pérennou,Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine,Volume 59, Issue 4, September 2016,Pages270-275

- ↑ Kumar, Kvijaya; Suresh, BV; Misri, ZK; Chakrapani, M; Mohan, Uthra; Babu, Skarthik (2013). "Effectiveness of mirror therapy on lower extremity motor recovery, balance and mobility in patients with acute stroke: A randomized sham-controlled pilot trial". Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 16 (4): 634–9. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.120496. PMC 3841617. PMID 24339596.

- ↑ Mei Toh, Sharon Fong; Fong, Kenneth N.K (2012). "Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Mirror Therapy in Training Upper Limb Hemiparesis after Stroke". Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy. 22 (2): 84–95. doi:10.1016/j.hkjot.2012.12.009.

- ↑ Darbois, Nelly; Guillaud, Albin; Pinsault, Nicolas (2018). "Do Robotics and Virtual Reality Add Real Progress to Mirror Therapy Rehabilitation? A Scoping Review". Rehabilitation Research and Practice. 2018. doi:10.1155/2018/6412318.

External links

- Ramachandran's website

- WNYC - Radio Lab: Where Am I? (May 5, 2006) downloadable segment of radio program looks at historical examples and a present-day case of phantom limbs

- Ramachandran's Reith Lecture on Phantom Limbs

- Mirror box therapy web site

- The Itch a The New Yorker article that discusses mirror therapy and its current, and possible future, uses.

- Mirror therapy aiding US amputees