Miranda July

| Miranda July | |

|---|---|

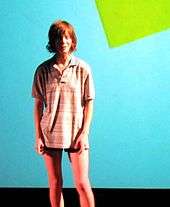

July at the Berlin International Film Festival 2011 | |

| Born |

Miranda Jennifer Grossinger February 15, 1974 Barre, Vermont, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actress, film director, screenwriter, singer, artist, author |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 1 |

Miranda July (born Miranda Jennifer Grossinger; February 15, 1974) is an American film director, screenwriter, singer, actress, author and artist. Her body of work includes film, fiction, monologue, digital media presentations, and live performance art.

She wrote, directed and starred in the films Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005) and The Future (2011). She wrote the book of short stories No One Belongs Here More Than You (2007) and the novel The First Bad Man (2015).

Early life

July was born in Barre, Vermont, in 1974,[1] the daughter of Lindy Hough and Richard Grossinger. Her parents, who taught at Goddard College at the time, are both writers.[2] Her parents founded North Atlantic Books, a publisher of alternative health, martial arts, and spiritual titles.[3][4] Her father was Jewish, whereas her mother was Protestant.[5]

July was encouraged to work on her short fiction by author and friend of a friend Rick Moody.[6] She grew up in Berkeley, California, where she first began staging plays at a local punk rock club.[7] She attended The College Preparatory School in Oakland for high school.[3] She later attended UC Santa Cruz, dropping out in her sophomore year.[7]

After leaving college, she moved to Portland, Oregon, and took up performance art. Her performances were successful; she has been quoted as saying she has not worked a day job since she was 23 years old.[8]

Filmmaking

Joanie4Jackie

Immersed in the riot grrl scene in Portland and motivated by its DIY ethos, July began an effort that she described as "a free alternative distribution system for women movie-makers".[9] The idea was to connect as many women artists as possible, let them see each other's work, and foster a sense of community.[10] Participants sent a self-made short film to July, who mailed back a compilation videotape containing that film and nine others – a "chainletter tape".[11] When it began in 1995, the project was called Big Miss Moviola but was soon renamed Joanie4Jackie.[12] July's first film, Atlanta, appears on the second tape of the series.[12] July continued to run the project for years, handing it off to the film department of Bard College in 2003.[13]

In 2017 the Getty Research Institute announced that they had acquired an archive of Joanie4Jackie as a donation from July. The collection includes more than 200 titles from the 1990s and 2000s, videos from Joanie4Jackie events, booklets, posters, hand-written letters from participants, and other documentation. Thomas W. Gaehtgens, the director of the Getty Research Institute, stated that the acquisition is "an esteemed addition to our Special Collections that connects to work by many important 20th century artists who are also represented in our archives, such as Eleanor Antin, Yvonne Rainer and Carolee Schneemann."[14]

Me and You and Everyone We Know

Filmmaker rated her number one in their "25 New Faces of Indie Film" in 2004. After winning a slot in a Sundance workshop, she developed her first feature-length film, Me and You and Everyone We Know, which opened in 2005.

The film won The Caméra d'Or prize in The Cannes Festival 2005[15] as well as the Special Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival, Best First Feature at the Philadelphia Film Festival, Feature Audience Award for Best Narrative Feature at the San Francisco International Film Festival, and the Audience Award for Best Narrative Feature at the Los Angeles Film Festival.[16]

The Future

On May 16, 2007, July mentioned that she was currently working on a new film. This film was originally titled "Satisfaction" but was later renamed The Future, with July in a lead role.[17] The film premiered at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival.[18]

Other film achievements

Wayne Wang consulted with July about aspects of his feature-length film The Center of the World (2001),[19] for which she received a story credit.[20]

On June 29, 2016, July was one of 683 artists and executives invited to join the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences as a writer.[21]

Music and spoken word

She recorded her first EP for Kill Rock Stars in 1996, titled Margie Ruskie Stops Time, with music by The Need.[22] She released two full-length LPs, 10 Million Hours A Mile in 1997 and The Binet-Simon Test in 1998, both on Kill Rock Stars.[23] She collaborated with Calvin Johnson in his musical project Dub Narcotic Sound System,[22] and in 1999 she made a split EP with IQU, released on Johnson's K Records.[24]

Acting

July has acted in many of her own short films, including Atlanta, The Amateurist, Nest of Tens, Are You The Favorite Person of Anyone?, and her feature-length films Me and You and Everyone We Know and The Future. She also made an appearance in the film Jesus' Son (1998).[20] She appeared in an episode of Portlandia in 2012.[25] She co-starred in Josephine Decker’s 2018 feature film, Madeline's Madeline.[26]

Live performance pieces

In 1998, July made Love Diamond, her first full-length multimedia performance piece – in her description, a "live movie."[22] She performed it at venues around the country, including the New York Video Festival, The Kitchen, and Yoyo A Go Go in Olympia.

She created her next major full-length performance piece, The Swan Tool, in 2000, also in collaboration with Love, with digital production work by Mitsu Hadeishi. She performed this piece in venues around the world, including the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art, the International Film Festival Rotterdam, the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.[27]

In 2006, after completing her first feature film, she went on to create another multimedia piece, Things We Don’t Understand and Definitely Are Not Going To Talk About, which she performed in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York.[28] This stage show contained several ideas that would become key elements of her later film, The Future.[22]

In March 2015, July premiered her performance work New Society as part of the 58th San Francisco International Film Festival.[29] In the program for the performance, July requested the audience not share details of the show, stating it is now "a rare sensation to sit down in a theater with no idea what will happen."[30]

Various art projects

With artist Harrell Fletcher, July founded the online arts project called Learning to Love You More (2002–2009). The project's website offered assignments to artists whose submissions became part of "an ever-changing series of exhibitions, screenings and radio broadcasts presented all over the world".[31] In addition to its Internet presentations, Learning to Love You More also compiled exhibitions for the Whitney Museum, the Seattle Art Museum, and other hosts.[31][32] A book version of the project's online art was released in 2007.[32][33] Starting May 1, 2009 the project's website stopped accepting assignment submissions. In 2010 the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art acquired the website, in order to preserve it as an archive of the project online.[34]

July constructed a sculptural exhibition, Eleven Heavy Things, for the 2009 Venice Biennale.[35] Its assortment of cartoonish shapes, made sturdy with fiberglass and steel, were designed for playful interaction by visitors.[36] The exhibition was also shown in New York City at Union Square Park and in Los Angeles at the MOCA Pacific Design Center.[35]

In 2013 she organized We Think Alone, an art project involving the private emails of public figures. Unredacted except for the recipients' names, the emails were freely donated by a disparate group of notable persons including author Sheila Heti, theoretical physicist Lee Smolin, basketball player Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and actress Kirsten Dunst. July grouped selected emails by topic, and sent a new set to the project's subscribers every week for 20 weeks.[37][38] As one reviewer described them, the emails are "simultaneously mundane and eerily revealing; they shed light on how people in the public eye craft their private identities... [they] also underscore, in some way, the way all of us present ourselves over email: excessively formal or passive-aggressive, lovey-dovey, flakey, overly excited."[38]

In 2014 she created an iOS app, Somebody,[39] which allows users to compose a message to be delivered to someone else in-person, or to deliver someone else's message in-person. When you send your friend a message through Somebody, it goes — not to your friend — but to the Somebody user nearest your friend. This person (likely a stranger) delivers the message verbally, acting as your stand-in. Somebody is a far-reaching public art project that incites performance and twists our love of avatars and outsourcing — every relationship becomes a three-way. The project was funded by Miu Miu.[40] The app closed on October 31, 2015.[41]

Writing

Her short story The Boy from Lam Kien was published in 2005 by Cloverfield Press, as a special-edition book with illustration by Elinor Nissley and Emma Hedditch. Another short story, Something That Needs Nothing, was published in the following year by The New Yorker.[42]

No One Belongs Here More Than You

No One Belongs Here More Than You, July's collection of short vignettes, was published by Scribner in 2007.[43]

It won the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award on September 24, 2007.[44] In her review for The New York Times, reviewer Sheelah Kolhatkar gave the collection a mixed review writing, "A handful of these stories are sweet and revealing, although in many cases the attempt to create "art" is too self-conscious, and the effort comes off as pointlessly strange."[43]

As of 2015 the collection has more than 200,000 copies in circulation.[45]

It Chooses You

July's non-fiction story collection It Chooses You was published by McSweeney's in 2011.[46]

While procrastinating the writing of her screenplay The Future in 2009, July crisscrossed Los Angeles accompanied by photographer Brigitte Sireto to meet a random selection of PennySaver sellers, glimpsing thirteen surprisingly moving and profoundly specific realities, along the way shaping her film, and herself, in unexpected ways.[47]

The First Bad Man

July's first novel The First Bad Man was published by Scribner in January 2015.[48] The narrative centers around Cheryl Glickman, a middle-aged woman in crisis whose life abruptly changes course when a young woman, named Clee, moves into her home.[48][49] The novel explores the complex relationship between Cheryl and Clee.[50]

In her review for The New York Times Book Review, reviewer Lauren Groff writes The First Bad Man "makes for a wry, smart companion on any day. It's warm. It has a heartbeat and a pulse. This is a book that is painfully alive."[50]

Personal life

July is married to artist and film director Mike Mills, with whom she has a son.[51][52]

In a 2007 interview with Bust magazine, July spoke of the importance which feminism has had in her life, saying, "What's confusing about [being a feminist]? It's just being pro-your ability to do what you need to do. It doesn't mean you don't love your boyfriend or whatever...When I say 'feminist', I mean that in the most complex, interesting, exciting way!"[53]

July expressed her views on intersectionality and education in a 2017 interview with Vice: "I too have learned so much in the past few years, and I love that we've become so articulate and conscious and educated and aware of intersectionality...but I don't think the way to say thank you for all that education is to just sit back and hold it inside, and be smart alone in your room."[54]

Filmography

Full length films by July

- Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005) – wrote, directed, and acted

- The Future (2011) – wrote, directed, and acted

- Untitled Miranda July Project (2019) - wrote and directed

Full length films with contributions by July

- Jesus' Son (1999) (Lions Gate Entertainment) – acted

- The Center of the World (2001) – co-wrote story

- Madeline's Madeline (2018) – acted

Short films by July

- I Started Out With Nothing and I Still Have Most of It Left[55]

- Atlanta (1996) – appeared on Audio-Cinematic Mix Tape (Peripheral Produce)

- The Amateurist (1997) – part of Joanie4Jackie4Ever

- A Shape Called Horse (1999) – appeared on Video Fanzine #1 (Kill Rock Stars)

- Nest of Tens (1999) (Peripheral Produce)

- Getting Stronger Every Day (2001) – 6 mins 30 secs,[56] appeared on Peripheral Produce: All-Time Greatest Hits: a collection of experimental films and videos (Peripheral Produce)

- Haysha Royko (2003) – 4 mins[57]

- Are You the Favorite Person of Anybody? (2005)[55] – appeared on Wholphin issue 1

- Somebody (2014), Miu Miu's Women's Tales 8 – 10 mins 14 secs

- Miranda July Introduces the Miranda (2014) – advertisement for a handbag designed by July and Welcome Companions. With music by JD Samson.

Short films with contributions by July

- The Portland Girl Convention (1996) by Emily B. Kingan – documentary

- The Subconscious Art of Graffiti Removal (2001) by Matt McCormick – with narration by July[58]

Music videos

- "Get Up" by Sleater-Kinney – directed by July[59]

- "Top Ranking" by Blonde Redhead – July acts in the video, directed by Mike Mills[60]

Publications

Full length publications by July

Full length publications with others

- Learning to Love You More. Munich: Prestel Publishing, 2007. With Harrell Fletcher. ISBN 978-3791337333.

- It Chooses You. McSweeney's, Irregulars, 2011. With photographs by Brigitte Sire. ISBN 9781936365012.

Short stories by July

- Jack and Al (Fall 2002) (Mississippi Review)

- The Moves (Spring 2003) (Tin House)

- This Person (Spring 2003) (Bridge Magazine)

- Birthmark (Spring 2003) (Paris Review)

- Frances Gabe's Self Cleaning House (Fall 2003) (Nest)

- It Was Romance (Fall 2003) (Harvard Review)

- Making Love in 2003 (Fall 2003) (Paris Review)

- The Man on the Stairs (Spring/Summer 2004) (Fence Magazine])

- The Boy from Lam Kien. Los Angeles: Cloverfield Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0976047827.

- The Shared Patio (Winter 2005) (Zoetrope: All-Story)

- Something That Needs Nothing (September 18, 2006) (The New Yorker)

- Majesty (September 28, 2006) (Timothy McSweeney's Quarterly Concern)

- The Swim Team (January 2007) (Harper's Magazine)

- Roy Spivey (June 11, 2007) (The New Yorker)

- The Metal Bowl (September 4, 2017) (The New Yorker)

Performances

- Love Diamond (1998–2000)

- The Swan Tool (2000–2002)

- How I Learned to Draw (2002–2003)

- Things We Don't Understand and Are Definitely Not Going to Talk About (2006–present)

- New Society (2015)

Discography

Albums

- 10 Million Hours a Mile (1997) (Kill Rock Stars)

- The Binet-Simon Test (1998) (Kill Rock Stars)

EPs

Awards

- 2002: Creative Capital Emerging Fields Award[61]

References

- ↑ Morris, Wesley (June 26, 2005). "Putting all they know to work". The Boston Globe. Retrieved June 27, 2012. (subscription required)

- ↑ "The Miranda July Story". Underground Literary Alliance. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- 1 2 Dinkelspiel, Frances (August 17, 2011). "Me and You and Miranda July and Berkeley". Berkeleyside. Archived from the original on September 1, 2016.

- ↑ "North Atlantic Books". North Atlantic Books. Archived from the original on 2013-09-15.

- ↑ Onstad, Katrina (2011-07-14). "Miranda July, The Make-Believer". The New York Times.

- ↑ Ashman, Angela (2007-05-08). "You and Her and Everything She Knows". The Village Voice.

- 1 2 Hackett, Regina (May 30, 2005). "A moment with performance artist/filmmaker Miranda July". SeattlePi.com. Archived from the original on November 13, 2017.

- ↑ Johnson, G. Allen (2005-06-29). "Performance artist's new role – film director". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2006-04-11.

- ↑ Columpar, Corinn; Mayer, Sophie (2009). There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Wayne State University Press. p. 24.

- ↑ Bryan-Wilsonn, Julia (February 2017). "Joanie4Jackie". ArtForum. Archived from the original on February 8, 2018.

- ↑ Syfret, Wendy (January 30, 2017). "Welcome to Joanie4Jackie — Miranda July's 90s feminist film project". Vice Media. Archived from the original on February 8, 2018.

- 1 2 Tang, Estelle (January 30, 2017). "How This Underground Feminist Art Project Turned Miranda July Into a Filmmaker". Elle. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017.

- ↑ Columpar & Mayer, pp.24–25.

- ↑ Vankin, Deborah (2017-01-30). "The Getty acquires Miranda July's feminist DIY video archive for 'Joanie 4 Jackie'". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ↑ "Cannes 2005: The Winners". indieWIRE.com. 2005-05-21. Archived from the original on November 30, 2006. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ↑ "Me and You and Everyone We Know". IFC Films. 2005. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ↑ Finding 'Satisfaction' Variety, May 15, 2008.

- ↑ Olsen, Mark (2011-01-21). "Sundance Film Festival: Miranda July looks into 'The Future'". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Kaufman, Anthony (April 20, 2001). "INTERVIEW: Wayne Wang Journeys to "The Center of the World"". IndieWire. Archived from the original on November 10, 2016.

- 1 2 Rabin, Nathan (July 6, 2005). "INTERVIEW: Miranda July". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on January 23, 2018.

- ↑ "NEW MEMBERS 2016: ACADEMY INVITES 683 TO MEMBERSHIP". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. 2016-06-29. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- 1 2 3 4 Peloquin, Jahna (August 17, 2012). "Miranda July's bright Future". Star Tribune. Minneapolis, MN. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018.

- ↑ Miranda July discography at AllMusic. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ↑ Taylor, Ken. Girls on Dates review at AllMusic. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ↑ Locker, Melissa (February 11, 2012). "Watch: Miranda July Visits "Portlandia"". IFC. Archived from the original on January 21, 2018.

- ↑ Ebiri, Bilge (January 28, 2018). ""Madeline's Madeline": The Best Film I Saw at Sundance". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018.

- ↑ Brooks, Xan (2001-03-06). "Film review: Miranda July". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

- ↑ "Miranda July: performances". MirandaJuly.com. Archived from the original on 2007-07-10. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ↑ "San Francisco Film Society and SFMOMA Co-Present Miranda July's 'New Society' at 58th San Francisco International Film Festival". San Francisco Film Society. 2015-03-03. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

- ↑ Brantley, Ben (2015-10-11). "Review: In Miranda July's 'New Society', the Audience Makes the Show". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

- 1 2 Yuri Ono (designer) (2009). "Hello". Learningtoloveyoumore.com. Miranda July; Harrell Fletcher. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- 1 2 Staff (2009). "Current Perspectives lecture series, Spring 2009: Harrell Fletcher". Kcai.edu. Kansas City Art Institute. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ↑ July, Miranda; Fletcher, Harrell (2007). Learning to Love You More. Munich; New York: Prestel. ISBN 3791337335.

- ↑ "Learning To Love You More". www.learningtoloveyoumore.com. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- 1 2 Staff (July 21, 2011). "Art: July's 'Eleven Heavy Things' comes to MOCA center". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015.

- ↑ Gopnik, Blake (August 11, 2011). "Photos: Miranda July's Eleven Heavy Things Art in Los Angeles". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on February 9, 2018.

- ↑ Staff (July 6, 2013). "Miranda July: From The Outboxes Of The Noteworthy". NPR. Archived from the original on January 25, 2018.

- 1 2 Wilkinson, Isabel (July 2, 2013). "Miranda July on 'We Think Alone,' Her New Email Project". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018.

- ↑ Stinson, Liz. "Miranda July Creates an App That Doubles as a Social Experiment". Wired. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ↑ Alter, Alexandar (January 9, 2015). "An Escape Artist, Unlocking Door After Door Miranda July Blurs Fiction and Reality to Promote a Novel". The New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ↑ http://somebodyapp.com/

- ↑ July, Miranda (September 18, 2006). "Fiction: "Something That Needs Nothing"". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. pp. 68–77.

- 1 2 Kolhatkar, Sheelah (July 1, 2007). "Cringe Festival". The New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ↑ Lea, Richard (September 24, 2007). "Award-winning film-maker scoops short story prize". London, UK: guardian.co.uk. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ↑ Alter, Alexandra (January 10, 2015). "An Escape Artist, Unlocking Door After Door Miranda July Blurs Fiction and Reality to Promote a Novel". The New York Times. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ↑ 1974-, July, Miranda,. It chooses you. Sire, Brigitte,. San Francisco, California. ISBN 9781936365012. OCLC 713187971.

- ↑ July, Miranda (2011). It Chooses You. San Francisco: McSweeney's. ISBN 1936365014.

- 1 2 Kakutani, Michiko. "Crouched Behind a Barricade, Until a Crude Stranger Barges In Miranda July's 'The First Bad Man'". The New York Times. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ↑ Miller, Laura (2015-02-11). "The First Bad Man by Miranda July review – strenuously quirky". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-10-12.

- 1 2 Groff, Lauren (January 18, 2015). "Sunday Book Review: 'The First Bad Man,' by Miranda July". The New York Times. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Judd Apatow vs. Miranda July". Huck Magazine. January 5, 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ↑ Hiebert, Paul (June 2, 2010). "Miranda July Makes Art That Requires People". Flavorwire. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ↑ Profile, Feministing.com; accessed April 5, 2017.

- ↑ ""what does it mean to have a £3 top next to a £3,000 top?" – Miranda July on religion, prejudice and luxury shopping". I-d. 2017-10-04. Retrieved 2017-10-12.

- 1 2 Kaleem Aftab, "Miranda July: A renaissance woman with a bright future", The Independent, 17 October 2011. Accessed 11 November 2017

- ↑ Xan Brooks, "Miranda July", The Guardian, 6 March 2001. Accessed 11 November 2017

- ↑ "Haysha Royko: Miranda July", Video Data Bank. Accessed 11 November 2017

- ↑ Wagner, Annie (August 23, 2007). "Anti-Graffiti Artists". The Stranger. Archived from the original on April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Get Up: Sleater-Kinney's last show: A retrospective". PitchforkMedia.com. 2006-08-28. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ↑ "Video: Blonde Redhead: "Top Ranking"". PitchforkMedia.com. 2007-05-24. Archived from the original on 2007-07-24. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ↑ "Miranda July: Emerging Fields". Creative Capital. 2002. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017.

Further reading

- Antje Czudaj: Miranda July’s Intermedial Art. The Creative Class Between Self-Help and Individualism. Transcript, 2016 – Antje Czudaj did her doctorate in American studies about Miranda July.

- Onstad, Katrina (July 17, 2011). "Miranda July Is Totally Not Kidding". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- "Miranda July Called Before Congress To Explain Exactly What Her Whole Thing Is". The Onion. January 21, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- Hoberman, J. (July 27, 2011). "In The Future, Miranda July Grows Up". The Village Voice. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Miranda July. |

Works

Interviews

- Maricich, Khaela (2007). "Interview with (and by) Miranda July". The Believer.

- Silverblatt, Michael (September 13, 2007). "Miranda July". Bookworm. KCRW.

- Head, Steve (April 30, 2011). "IFFBoston 2011 - Ep. #2 - Our Interview with Actress/Director Miranda July ('The Future')". The Post-Movie Podcast.

- Champion, Ed (July 26, 2011). "Miranda July (BSS #405)". The Bat Segundo Show.

- Sun, Carolyn (November 23, 2011). "Miranda July Talks About Her New Book 'It Chooses You'". The Daily Beast.