Millennialism

| Part of a series on |

| Eschatology |

|---|

|

|

Millennialism (from millennium, Latin for "a thousand years"), or chiliasm (from the Greek equivalent), is a belief advanced by some Christian denominations that a Golden Age or Paradise will occur on Earth in which Christ will reign for 1000 years prior to the final judgment and future eternal state (the "World to Come") of the New Heavens and New Earth. This belief derives primarily from Revelation 20:1–6. Millennialism is a specific form of millenarianism.

Similarities to millennialism appear in Zoroastrianism, which identified successive thousand-year periods, each of which will end in a cataclysm of heresy and destruction, until the final destruction of evil and of the spirit of evil by a triumphant king of peace at the end of the final millennial age. "Then Saoshyant makes the creatures again pure, and the resurrection and future existence occur" (Zand-i Vohuman Yasht 3:62).

Scholars have also linked various other social and political movements, both religious and secular, to millennialist metaphors.

Zoroastrism

The concept of a utopian millennium, and much of the imagery used by Jews and early Christians to describe this time period, was most likely influenced by Persian culture, specifically by Zoroastrianism. Zoroastrianism describes history as occurring in successive thousand-year periods, each of which will end in a cataclysm of heresy and destruction. These epochs will culminate in the final destruction of evil by a triumphant messianic figure, the Saoshyant, at the end of the last millennial age. The Saoshyant will perform a purification of the morally corrupted physical world, as described in the Zand-i Vohuman Yasht: "Saoshyant makes the creatures again pure, and the resurrection and future existence occur."[1] This eschatological event is referred to as Frashokereti, a notion that seems to have had a great degree of influence on Judaic eschatology and eventually Christian millennialism.

Christianity

Pre-Christian

Millennialism developed out of a uniquely Christian interpretation of Jewish apocalypticism, which took root in Jewish apocryphal literature of the tumultuous intertestamental period (200 BCE to 100 CE, including writings such as Enoch, Jubilees, Esdras, and the additions to Daniel. Passages within these texts, including 1 Enoch 6-36, 91-104, 2 Enoch 33:1, and Jubilees 23:27, refer to the establishment of a "millennial kingdom" by a messianic figure, occasionally suggesting that the duration of this kingdom would be a thousand years. However, the actual number of years given for the duration of the kingdom varied. In 4 Ezra 7:28-9, for example, it is said that the kingdom will last only 400 years.

This notion of the millennium no doubt helped some Jews to cope with the socio-political conflicts that they faced. This concept of the millennium served to reverse the previous period of evil and suffering, rewarding the virtuous for their courage while punishing the evil-doers, with a clear separation of those who are good from those who are evil. The vision of a thousand-year period of bliss for the faithful, to be enjoyed here in the physical world as "heaven on earth," exerted an irresistible power over the imagination of Jews in the inter-testamental period as well as early Christians. Millennialism, which had already existed in Jewish thought, received a new interpretation and fresh impetus with the arrival of Christianity.

In Christian scripture

Christian millennialist thinking is primarily based upon Revelation 20:1-6, which describes the vision of an angel who descended from heaven with a large chain and a key to a bottomless pit, and captured Satan, imprisoning him for a thousand years:

He seized the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is the Devil and Satan, and bound him for a thousand years and threw him into the pit and locked and sealed it over him, so that he would deceive the nations no more, until the thousand years were ended. After that, he must be let out for a little while.

— Rev. 20:2-3

The Book of Revelation then describes a series of judges who are seated on thrones, as well as his vision of the souls of those who were beheaded for their testimony in favor of Jesus and their rejection of the mark of the beast. These souls:

came to life and reigned with Christ a thousand years. (The rest of the dead did not come to life until the thousand years were ended.) This is the first resurrection. Blessed and holy are those who share in the first resurrection. Over these the second death has no power, but they will be priests of God and of Christ, and they will reign with him a thousand years

— Rev. 20:4-6

Thus, John of Patmos characterizes a millennium where Christ and the Father will rule over a theocracy of the righteous. While there are an abundance of biblical references to such a kingdom of God throughout the Old and New Testaments, this is the only literal reference in the Bible to such a period lasting one thousand years. The literal belief in a thousand-year reign of Christ is a later development in Christianity, as it does not seem to have been present in first century texts.

Early church

During the first centuries after Christ, various forms of chiliasm (millennialism) were to be found in the Church, both East and West.[2] It was a decidedly majority view at that time, as admitted by Eusebius, himself an opponent of the doctrine:

The same writer gives also other accounts which he says came to him through unwritten tradition, certain strange parables and teachings of the Saviour, and some other more mythical things. To these belong his statement that there will be a period of some thousand years after the resurrection of the dead, and that the kingdom of Christ will be set up in material form on this very earth. I suppose he got these ideas through a misunderstanding of the apostolic accounts, not perceiving that the things said by them were spoken mystically in figures. For he appears to have been of very limited understanding, as one can see from his discourses. But it was due to him that so many of the Church Fathers after him adopted a like opinion, urging in their own support the antiquity of the man; as for instance Irenaeus and any one else that may have proclaimed similar views.

— Eusebius, The History of the Church, Book 3:39:11-13[3]

Nevertheless, strong opposition later developed from some quarters, most notably from Augustine of Hippo. The Church never took a formal position on the issue at any of the ecumenical councils, and thus both pro and con positions remained consistent with orthodoxy. The addition to the Nicene Creed was intended to refute the perceived Sabellianism of Marcellus of Ancyra and others, a doctrine which includes an end to Christ's reign and which is explicitly singled out for condemnation by the council [Canon #1].[4][5] The Catholic Encyclopedia notes that the 2nd century proponents of various Gnostic beliefs (themselves considered heresies) also rejected millenarianism.[6]

Millennialism was taught by various earlier writers such as Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Commodian, Lactantius, Methodius, and Apollinaris of Laodicea in a form now called premillennialism.[7] According to religious scholar Rev. Dr. Francis Nigel Lee,[8] "Justin's 'Occasional Chiliasm' sui generis which was strongly anti-pretribulationistic was followed possibly by Pothinus in A.D. 175 and more probably (around 185) by Irenaeus". Justin Martyr, discussing his own premillennial beliefs in his Dialogue with Trypho the Jew, Chapter 110, observed that they were not necessary to Christians:

I admitted to you formerly, that I and many others are of this opinion, and [believe] that such will take place, as you assuredly are aware; but, on the other hand, I signified to you that many who belong to the pure and pious faith, and are true Christians, think otherwise.[9]

Melito of Sardis is frequently listed as a second century proponent of premillennialism.[10] The support usually given for the supposition is that "Jerome [Comm. on Ezek. 36] and Gennadius [De Dogm. Eccl., Ch. 52] both affirm that he was a decided millenarian."[11]

In the early third century, Hippolytus of Rome wrote:

And 6,000 years must needs be accomplished, in order that the Sabbath may come, the rest, the holy day "on which God rested from all His works." For the Sabbath is the type and emblem of the future kingdom of the saints, when they "shall reign with Christ," when He comes from heaven, as John says in his Apocalypse: for "a day with the Lord is as a thousand years." Since, then, in six days God made all things, it follows that 6, 000 years must be fulfilled. (Hippolytus. On the HexaËmeron, Or Six Days' Work. From Fragments from Commentaries on Various Books of Scripture).

Around 220, there were some similar influences on Tertullian, although only with very important and extremely optimistic (if not perhaps even postmillennial) modifications and implications. On the other hand, "Christian Chiliastic" ideas were indeed advocated in 240 by Commodian; in 250 by the Egyptian Bishop Nepos in his Refutation of Allegorists; in 260 by the almost unknown Coracion; and in 310 by Lactantius. Into the late fourth century, Bishop Ambrose of Milan had millennial leanings (Ambrose of Milan. Book II. On the Belief in the Resurrection, verse 108). Lactantius is the last great literary defender of chiliasm in the early Christian church. Jerome and Augustine vigorously opposed chiliasm by teaching the symbolic interpretation of the Revelation of St. John, especially chapter 20.[12]

In a letter to Queen Gerberga of France around 950, Adso of Montier-en-Der established the idea of a "last World Emperor" who would conquer non-Christians before the arrival of the Antichrist.[13]

Reformation and beyond

Christian views on the future order of events diversified after the Protestant reformation (c.1517). In particular, new emphasis was placed on the passages in the Book of Revelation which seemed to say that as Christ would return to judge the living and the dead, Satan would be locked away for 1000 years, but then released on the world to instigate a final battle against God and his Saints (Rev. 20:1–6). Previous Catholic and Orthodox theologians had no clear or consensus view on what this actually meant (only the concept of the end of the world coming unexpectedly, "like a thief in a night", and the concept of "the antichrist" were almost universally held). Millennialist theories try to explain what this "1000 years of Satan bound in chains" would be like.

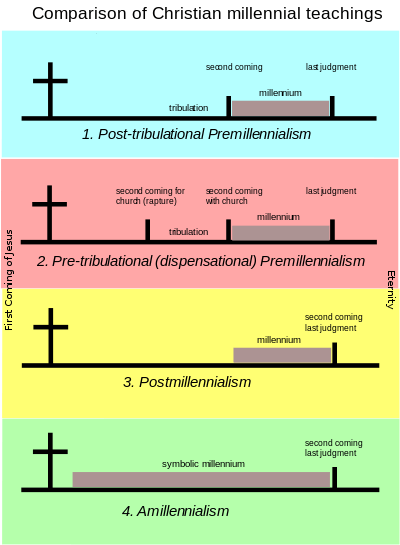

Various types of millennialism exist with regard to Christian eschatology, especially within Protestantism, such as Premillennialism, Postmillennialism, and Amillennialism. The first two refer to different views of the relationship between the "millennial Kingdom" and Christ's second coming.

Premillennialism sees Christ's second advent as preceding the millennium, thereby separating the second coming from the final judgment. In this view, "Christ's reign" will be physically on the earth.

Postmillennialism sees Christ's second coming as subsequent to the millennium and concurrent with the final judgment. In this view "Christ's reign" (during the millennium) will be spiritual in and through the church.

Amillennialism basically denies a future literal 1000 year kingdom and sees the church age metaphorically described in Rev. 20:1–6 in which "Christ's reign" is current in and through the church.

The Catholic Church strongly condemns millennialism as the following shows:

The Antichrist's deception already begins to take shape in the world every time the claim is made to realize within history that messianic hope which can only be realized beyond history through the eschatological judgment. The Church has rejected even modified forms of this falsification of the kingdom to come under the name of millenarianism, especially the "intrinsically perverse" political form of a secular messianism.

— Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1995[14]

Utopianism

The early Christian concept had ramifications far beyond strictly religious concern during the centuries to come, as it was blended and enhanced with ideas of utopia.

In the wake of early millennial thinking, the Three Ages philosophy developed. The Italian monk and theologian Joachim of Fiore (died 1202) claimed that all of human history was a succession of three ages:

- the Age of the Father (the Old Testament)

- the Age of the Son (the New Testament)

- the Age of the Holy Spirit (the age begun when Christ ascended into heaven, leaving the Paraclete, the third person of the Holy Trinity, to guide)

It was believed that the Age of the Holy Spirit would begin at around 1260, and that from then on all believers would be living as monks, mystically transfigured and full of praise for God, for a thousand years until Judgment Day would put an end to the history of our planet.

In the Modern Era, some of the concepts of millennial thinking have found their way into various secular ideas, usually in the form of a belief that a certain historical event will fundamentally change human society (or has already done so). For example, the French Revolution seemed to many to be ushering in the millennial age of reason. Also, the philosophies of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) and Karl Marx (1818–1883) carried strong millennial overtones. As late as 1970, Yale law teacher Charles A. Reich coined the term "Consciousness III" in his best seller The Greening of America, in which he spoke of a new age ushered in by the hippie generation. However, these secular theories generally have little or nothing to do with the original millennial thinking, or with each other.

The New Age movement was also highly influenced by Joachim of Fiore's divisions of time, and transformed the Three Ages philosophy into astrological terminology. The Age of the Father was recast as the Age of Aries, the Age of the Son became the Age of Pisces, and the Age of the Holy Spirit was called the Aquarian New Age. The current so-called "Age of Aquarius" will supposedly witness the development of a number of great changes for humankind, reflecting the typical features of millennialism.

Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses believe that Christ will rule from heaven for 1,000 years as king over the earth, assisted by 144,000 holy ones. The principal purpose of this millennial reign is to resolve the question of who legitimately deserves to be sovereign of the Earth and of the universe. It also serves to finally accomplish the Creator's original purpose of an Earth populated by a peaceful, satisfied and loving human society, descendants from the first human couple Adam and Eve. This will happen after the destruction of the wicked at Armageddon.

Armageddon will be a decisive battle between two opposing forces: on one side, Christ Jesus together with the holy angels; in opposition, human governments and institutions (manipulated by wicked spirits) insistent on maintaining control over humanity. Unlike natural or manmade catastrophes, Christ and his angels will selectively destroy those humans deemed incorrigible. Planet Earth will be rid of greed, corruption, and all individuals and institutions who impenitently ruin the earth and impose misery on others. (Rev 16:16; 1 John 5:19; Matthew 25:31–40)

Malevolent spiritual beings will be restrained and prevented from interfering in human affairs for the duration of Christ's reign. Free of untoward influences, the Witnesses see the 1,000 year reign as fulfillment of the Biblical promise of "New Heavens and a New Earth".

One aspect which differentiates Jehovah's Witnesses from other millennialists (such as Baptists, Church of God, Church of Christ, and other fundamentalist Christian groups) is the interpretation of 2 Peter 3:7, 13. Whereas the latter hold to a literal interpretation, namely that the planet Earth will be destroyed and replaced with another physical planet, Jehovah's Witnesses by contrast believe the language in 2 Peter 3:7 is figurative. Hence their understanding is that the literal planet Earth will not be destroyed but instead, the existing framework of human society, which includes greedy commerce, divisive religions and corrupt governments.

Christ's kingdom consists of those who govern (from heaven) and those who are governed (on earth). This government will accomplish in the comparatively short timespan of 1,000 years all the things human governments and institutions have promised (but failed to deliver) during thousands of years of rule, while experimenting every form of government imaginable. Jesus Christ, the Messiah, will be the 'head of state', or King officially designated by God. In turn, he will delegate authority to 144,000 select individuals, individually chosen by Jehovah from among humanity. Those chosen have already proven their complete allegiance to Jehovah God and to His legitimate right to govern. The first to be promised this privilege were the faithful apostles of Jesus Christ in the 1st century C.E. The rulers will be loving and fair, always intent on the common good of everyone.

On the earth, those who are kept safe through that 'great tribulation' (Matt 24:21; Rev 7:9) and the subsequent destruction of the world ruled by Satan the Devil will be ushered into a just, peaceful, and equitable earthwide society of humans. During the millennium, Christ will use his power to cure every sort of sickness (Rev 22:17), malady, and infirmity. Ultimately everyone who accepts living by Jehovah God's righteous standards (Exodus 20:1–17) will attain perfect health. Guided by the heavenly government, humans will work to progressively establish an earthwide paradise (Matt 19:27,28). Hunger and poverty will be completely eliminated (Rev 21:1–5).

Humans who died during all prior human history (but who were not deemed incorrigible) will be resurrected (or recreated) on the earth during the 1,000 years. These will have the opportunity to fully integrate into society (Isaiah 65:17).

At the culmination of the millennium, Christ will cede control of planet Earth to his Father Jehovah (1 Cor 15:28) and will himself acknowledge and accept Jehovah's right to rule (or sovereignty). The restraints on wicked spirit creatures will be removed and all humanity will face a test. With full understanding, each human must individually choose whether to accept or reject God's right to rule, his sovereignty. Those humans and (previously restrained) spirit creatures who reject rule by Jehovah God, showing themselves to be menaces to human society and the remainder of the universe, will be completely and permanently eliminated. For any of these who may have been resurrected, this will literally be a "second" death. Thereafter, obedient humankind will live forever on the earth and Jehovah God's original purpose for the earth will be accomplished. (Gen 1:28)

Baha'i Faith

Bahá'u'lláh mentioned in the Kitáb-i-Íqán that God will renew the "City of God" about every thousand years,[15] and specifically mentioned that a new Manifestation of God would not appear within 1000 years (1893-2893) of Bahá'u'lláh's message, but that the authority of Bahá'u'lláh's message could last up to 500,000 years.[16][17]

Theosophy

The Theosophist Alice Bailey taught that Christ (in her books she refers to the powerful spiritual being best known by Theosophists as Maitreya as The Christ or The World Teacher, not as Maitreya) would return “sometime after AD 2025”, and that this would be the New Age equivalent of the Christian concept of the Second Coming of Christ.[18][19] Bailey stated that St. Germain (referred to by Bailey in her books as The Master Rakoczi or The Master R.) is the manager of the executive council of the Christ.[20] According to Bailey, when Christ returns he will stay the entire approximately 2,000 years period of the Age of Aquarius and thus the New Age equivalent of the Millennial Age, when Maitreya will reign as the spiritual leader of Earth as the Messiah who will bring world peace, will not be just a single millennium but will be the Aquarian bimillennium.

Nazism

The most controversial interpretation of the Three Ages philosophy and of millennialism in general is Adolf Hitler's "Third Reich" ("Drittes Reich"), which in his vision would last for a thousand years to come ("Tausendjähriges Reich"), but which ultimately only lasted for 12 years (1933–1945).

The phrase "Third Reich" was originally coined by the German thinker Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, who in 1923 published a book titled Das Dritte Reich. Looking back at German history, he distinguished two separate periods, and identified them with the ages of Joachim of Fiore:

- the Holy Roman Empire (beginning with Charlemagne in AD 800) – (the "First Reich") – The Age of the Father and

- the German Empire – under the Hohenzollern dynasty (1871–1918) (the "Second Reich") – The Age of the Son.

After the interval of the Weimar Republic (1918–1933), during which constitutionalism, parliamentarism and even pacifism ruled, these were then to be followed by:

- the "Third Reich" – The Age of the Holy Ghost.

Although van den Bruck was unimpressed by Hitler when he met him in 1922 and did not join the Nazi Party, the phrase was nevertheless adopted by the Nazis to describe the totalitarian state they wanted to set up when they gained power, which they succeeded in doing in 1933. Later, however, the Nazi authorities banned the informal use of "Third Reich" throughout the German press in the summer of 1939, instructing it to use more official terms such as "German Reich", "Greater German Reich", and "National Socialist Germany" exclusively.[21]

During the early part of the Third Reich many Germans also referred to Hitler as being the German Messiah, especially when he conducted the Nuremberg Rallies, which came to be held at a date somewhat before the Autumn Equinox in Nuremberg, Germany.

In a speech held on 27 November 1937, Hitler commented on his plans to have major parts of Berlin torn down and rebuilt:

- [...] einem tausendjährigen Volk mit tausendjähriger geschichtlicher und kultureller Vergangenheit für die vor ihm liegende unabsehbare Zukunft eine ebenbürtige tausendjährige Stadt zu bauen [...].

- [...] to build a millennial city adequate [in splendour] to a thousand year old people with a thousand year old historical and cultural past, for its never-ending [glorious] future [...]

After Adolf Hitler's unsuccessful attempt to implement a thousand-year-reign, the Vatican issued an official statement that millennial claims could not be safely taught and that the related scriptures in Revelation (also called the Apocalypse) should be understood spiritually. Catholic author Bernard LeFrois wrote:

- Millenium [sic]: Since the Holy Office decreed (July 21, 1944) that it cannot safely be taught that Christ at His Second Coming will reign visibly with only some of His saints (risen from the dead) for a period of time before the final and universal judgment, a spiritual millennium is seen in Apoc. 20:4–6. St. John gives a spiritual recapitulation of the activity of Satan, and the spiritual reign of the saints with Christ in heaven and in His Church on earth.[22]

Social movements

Millennial social movements are a specific form of millenarianism that are based on some concept of a one thousand-year cycle. Sometimes the two terms are used as synonyms, but this is not entirely accurate for a purist. Millennial social movements need not be religious, but they must have a vision of an apocalypse that can be utopian or dystopian. Those who are part of millennial social movements are "prone to be violent," with certain types of millennialism connected to violence. The first is progressive, where the "transformation of the social order is gradual and humans play a role in fostering that transformation." The second is catastrophic millennialism which "deems the current social order as irrevocable corrupt, and total destruction of this order is necessary as the precursor to the building of a new, godly order." However the link between millennialism and violence may be problematic, as new religious movements may stray from the catastrophic view as time progresses.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ "Zand-i Vohuman Yasht, chapter 3". www.avesta.org. Retrieved 2017-12-16.

- ↑ Theology Today, January 1996, Vol. 53, No. 4, pp. 464–476. On-line version here.

- ↑ Eusebius. Church History (Book III).

- ↑ Damick, Fr. Andrew Stephen (2011), Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy, Chesterton, IN: Ancient Faith Publishing, p. 23, ISBN 978-1-936270-13-2

- ↑ Luke 1:33 and Stuart Hall, Doctrine and Practice of the Early Church (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1992), 171.

- ↑ Kirsch J.P. Transcribed by Donald J. Boon. Millennium and Millenarianism

- ↑ JOUR295

- ↑ The Works of Rev. Prof. Dr. F.N. Lee

- ↑ Dialogue with Trypho (Chapters 80–81)

- ↑ Taylor, Voice of the Church, P. 66; Peters, Theocratic Kingdom, 1:495; Walvoord, Millennial Kingdom, p. 120; et al.

- ↑ Richard Cunningham Shimeall, Christ's Second Coming: Is it Pre-Millennial or Post-Millennial? (New York: John F. Trow, 1865), p. 67. See also, Taylor, p. 66; Peters, 1:495; Jesse Forest Silver, The Lord’s Return (New York, et al.: Fleming H. Revell Co., 1914), p. 66; W. Chillingworth, The Works of W. Chillingworth, 12th ed. (London: B. Blake, 1836), p.714; et al.

- ↑ Gawrisch, Wilbert (1998). Eschatological Prophecies and Current Misinterpretations in Our Great Heritage, Volume 3. Milwaukee: Northwestern Publishing House. pp. 688–689. ISBN 0810003791.

- ↑ https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/apocalypse/primary/adsoletter.html

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church. Imprimatur Potest +Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger. Doubleday, NY 1995, p. 194.

- ↑ The Kitáb-i-Íqán, pg. 199.

- ↑ McMullen, Michael D. (2000). The Baha'i: The Religious Construction of a Global Identity. Atlanta, Georgia: Rutgers University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-8135-2836-4.

- ↑ The Kitáb-i-Aqdas, gr. 37.

- ↑ Bailey, Alice A. The Externalisation of the Hierarchy New York:1957 Lucis Publishing Co. Page 530

- ↑ Bailey, Alice A. The Reappearance of the Christ New York:1948 Lucis Publishing Co.

- ↑ Bailey, Alice A. The Externalisation of the Hierarchy New York: 1957 – Lucis Press (Compilation of earlier revelations by Alice A. Bailey) Page 508

- ↑ Schmitz-Berning, Cornelia (2000). Vokabular des Nationalsozialismus. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, 10875 Berlin, pp. 159–160. (in German)

- ↑ LeFrois, Bernard J. Eschatological Interpretation of the Apocalypse. The Catholic Biblical Quarterly, Vol. XIII, pp. 17–20; Cited in Culleton RG. The Reign of Antichrist, 1951. Reprint TAN Books, Rockford (IL), 1974, p. 9

- ↑ Lewis (2004). Lewis, James R., ed. The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514986-6.

Bibliography

- Barkun, Michael. Disaster and the Millennium (Yale University Press, 1974) ( ISBN 0-300-01725-1)

- Case, Shirley J. The Millennial Hope, The University of Chicago Press, 1918.

- Cohn, Norman. The Pursuit of the Millennium: Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages, (2nd ed. Yale U.P., 1970).

- Desroches, Henri, Dieux d'hommes. Dictionnaire des messianismes et millénarismes de l'ère chrétienne, The Hague: Mouton, 1969,

- Ellwood, Robert. "Nazism as a Millennialist Movement", in Catherine Wessinger (ed.), Millennialism, Persecution, and Violence: Historical Cases (Syracuse University Press, 2000). ( ISBN 0-8156-2809-9 or ISBN 0-8156-0599-4)

- Fenn, Richard K. The End of Time: Religion, Ritual, and the Forging of the Soul (Pilgrim Press, 1997). ( ISBN 0-8298-1206-7 or ISBN 0-281-04994-7)

- Hall, John R. Apocalypse: From Antiquity to the Empire of Modernity, (Cambridge, UK: Polity 2009). ( ISBN 978-0-7456-4509-4 [pb] and ISBN 978-0-7456-4508-7)

- Kaplan, Jeffrey. Radical Religion in America: Millenarian Movements from the Far Right to the Children of Noah (Syracuse University Press, 1997). ( ISBN 0-8156-2687-8 or ISBN 0-8156-0396-7)

- Landes, Richard. Heaven on Earth: The Varieties of the Millennial Experience, (Oxford University Press 2011)

- Pentecost, J. Dwight. Things to Come: A study in Biblical Eschatology(Zondervan, 1958) ISBN 0-310-30890-9 and ISBN 978-0-310-30890-4.

- Redles, David. Hitler's Millennial Reich: Apocalyptic Belief and the Search for Salvation (New York University Press, 2005). ( ISBN 978-0-8147-7621-6 or ISBN 978-0-8147-7524-0)

- Stone, Jon R., ed. Expecting Armageddon: Essential Readings in Failed Prophecy (Routledge, 2000). ( ISBN 0-415-92331-X)

- Wessinger, Catherine. ed. The Oxford Handbook of Millennialism (Oxford University Press, 2011) 768 pp. ISBN 978-0-19-530105-2 online review

- Wistrich, Robert. Hitler’s Apocalypse: Jews and the Nazi Legacy (St. Martin’s Press, 1985). ( ISBN 0-312-38819-5)

- Wojcik, Daniel (1997). The End of the World as We Know It: Faith, Fatalism, and Apocalypse in America. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-9283-9.