Mictlāntēcutli

Mictlāntēcutli (Nahuatl pronunciation: [mik.t͡ɬaːn.ˈtéːkʷ.t͡ɬi], meaning "Lord of Mictlan"), in Aztec mythology, was a god of the dead and the king of Mictlan (Chicunauhmictlan), the lowest and northernmost section of the underworld. He was one of the principal gods of the Aztecs and was the most prominent of several gods and goddesses of death and the underworld. The worship of Mictlantecuhtli sometimes involved ritual cannibalism, with human flesh being consumed in and around the temple.[1]

Two life-size clay statues of Mictlantecuhtli were found marking the entrances to the House of Eagles to the north of the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan.[2]

Attributes

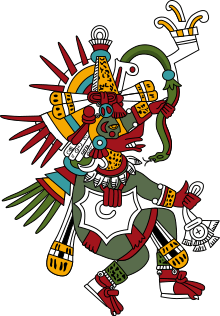

Mictlantecuhtli was 6 feet tall and was depicted as a blood-spattered skeleton or a person wearing a toothy skull.[4] Although his head was typically a skull, his eye sockets did contain eyeballs.[5] His headdress was shown decorated with owl feathers and paper banners and he wore a necklace of human eyeballs,[4] while his earspools were made from human bones.[6]

He was not the only Aztec god to be depicted in this fashion, as numerous other deities had skulls for heads or else wore clothing or decorations that incorporated bones and skulls. In the Aztec world, skeletal imagery was a symbol of fertility, health and abundance, alluding to the close symbolic links between life and death.[7] He was often depicted wearing sandals as a symbol of his high rank as Lord of Mictlan.[8] His arms were frequently depicted raised in an aggressive gesture, showing that he was ready to tear apart the dead as they entered his presence.[8] In the Aztec codices Mictlantecuhtli is often depicted with his skeletal jaw open to receive the stars that descend into him during the daytime.[6]

His wife was Mictecacihuatl,[4]and together they were said to dwell in a windowless house in Mictlan. Mictlantecuhtli was associated with spiders,[6] owls,[6] bats,[6] the eleventh hour and the northern compass direction, known as Mictlampa, the region of death.[9] He was one of only a few deities held to govern over all three types of souls identified by the Aztecs, who distinguished between the souls of people who died normal deaths (of old age, disease, etc.), heroic deaths (e.g. in battle, sacrifice or during childbirth), or non-heroic deaths. Mictlantecuhtli and his wife were the opposites and complements of Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, the givers of life.[3]

Mictlanteculhtli was the god of the day sign Itzcuintli (dog),[4] one of the 20 such signs recognised in the Aztec calendar, and was regarded as supplying the souls of those who were born on that day. He was seen as the source of souls for those born on the sixth day of the 13-day week and was the fifth of the nine Night Gods of the Aztecs. He was also the secondary Week God for the tenth week of the twenty-week cycle of the calendar, joining the sun god Tonatiuh to symbolise the dichotomy of light and darkness.

In the Colonial Codex Vaticanus 3738, Mictlantecuhtli is labelled in Spanish as "the lord of the underworld, Tzitzimitl, the same as Lucifer".[10]

Myths

In Aztec mythology, after Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca created the world, they put their creation in order and placed Mictlantecuhtli and his wife, Mictecacihuatl, in the underworld.[11]

According to Aztec legend, the twin gods Quetzalcoatl and Xolotl were sent by the other gods to steal the bones of the previous generation of gods from Mictlantecuhtli. The god of the underworld sought to block Quetzalcoatl's escape with the bones and, although he failed, he forced Quetzalcoatl to drop the bones, which were scattered and broken by the fall. The shattered bones were collected by Quetzalcoatl and carried back to the land of the living, where the gods transformed them into the various races of mortals.[12]

When a person died, they were interred with grave goods, which they carried with them on the long and dangerous journey to the underworld. Upon arrival in Mictlan these goods were offered to Mictlantecuhtli and his wife.[5]

In another myth, the sagacious (shrewd) god of death agrees to give the bones to Quetzalcóatl if he can completely finish what would appear to be a simple test.[13] The god informs Quetzalcóatl that he has to travel through his kingdom four times, while a shell sounds out like a trumpet. However, in place of giving Quetzalcóatl the shell from Mictlantecuhtl he gives him a normal shell, without holes in it. In order to not be mocked, Quetzalcóatl beckons the worms to come out and perforate the shell, thus creating holes. He then calls the bees to enter the shell and to make it sound out like a trumpet. (As an emblem of his power over wind and life, Quetzalcóatl is commonly depicted wearing a cut shell over his chest, this shell represents the same shell that Ehécatl, the god of the wind, wears).[14]

Whilst listening to the roar of the trumpet, Mictlantecuhtl, at first, decides to allow Quetzalcóatl to take all of the bones from the last creation, but then quickly changes his mind. Nevertheless, Quetzalcóatl is more astute than Mictlantecuhtl and his minions and escapes with the bones. Mictlantecuhtli, now very angry, orders his followers to create a very deep pit. While Quetzalcóatl is running away with the bones he is startled by a quail, which causes him to fall into the pit. He falls into the pit and dies (or so it would appear), and is subsequently tormented by the animal (the quail), and the bones he is carrying are scattered. The quail then begins to gnaw on the bones.

Despite the fall Quetzalcóatl is eventually revived and gathers all of the broken bones. It is for this reason that people today come in all different sizes. Once he has escaped from the underworld, Quetzalcóatl carries the precious cargo to Tamoanchan,[15] a place of miraculous origin.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Smith et al. 2003, p.245.

- ↑ Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, pp.60, 458.

- 1 2 Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.458.

- 1 2 3 4 Miller & Taube 1993, 2003, p.113.

- 1 2 Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.206.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fernández 1992, 1996, p.142.

- ↑ Smith 1996, 2003, p.206.

- 1 2 Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.434.

- ↑ Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, pp.54, 458.

- ↑ Klein 2000, pp.3–4.

- ↑ Read & González 2000, pp.193, 223.

- ↑ Miller & Taube 1993, 2003, p.113. Read & González 2000, p.224.

- ↑ Alfredo López, Olivier, Davidson, Austin, Guilhem, Russ (2015). The Myth of Quetzalcoatl: Religion, Rulership, and History in the Nahua World. Colorado: U Presso of Colorado.

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams (2005). The Oxford companion to world mythology. New York: Oxford U Press.

- ↑ Alfredo López, Austin (1997). Tamoanchan, Tlalocan: places of mist. Niwot, CO: U Pr. of Colorado.

References

Austin, Alfredo López (1997). Tamoanchan, Tlalocan: places of mist. Niwot, CO: U Pr. of Colorado. Print.

- Fernández, Adela (1996) [1992]. Dioses Prehispánicos de México (in Spanish). Mexico City: Panorama Editorial. ISBN 968-38-0306-7. OCLC 59601185.

- Klein, Cecelia F. (2000). "The Devil and the Skirt: An iconographic inquiry into the pre-Hispanic nature of the tzitzimime". Ancient Mesoamerica. Cambridge University Press. 11: 1–26. doi:10.1017/S0956536100111010.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo; Felipe Solis Olguín (2002). Aztecs. London: Royal Academy of Arts. ISBN 1-903973-22-8. OCLC 56096386.

- Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (2003) [1993]. An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27928-4. OCLC 28801551.

- Read, Kay Almere; Jason González (2000). Handbook of Mesoamerican Mythology. Handbooks of world mythology series. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-340-0. OCLC 43879188.

- Smith, Michael E. (2003). The Aztecs (second ed.). Malden, MA; Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23016-5. OCLC 48579073.

- Smith, Michael E.; Jennifer B. Wharton; Jan Marie Olson (2003). "Aztec Feasts, Rituals and Markets". In Tamara L Bray (ed.). Archaeology and Politics of Food and Feasting in Early States and Empires. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishing. pp. 235–270. ISBN 0-306-47730-0. OCLC 52165853.

Leeming, David Adams (2005).The Oxford companion to world mythology. New York: Oxford U Press. Print.

Austin, Alfredo López, Guilhem Olivier, and Russ Davidson (2015).The Myth of Quetzalcoatl: Religion, Rulership, and History in the Nahua World. Boulder: U Press of Colorado. Print.

External links

![]()