Michael O'Flanagan

Father Michael O'Flanagan (Irish: An tAthair Mícheál Ó Flannagáin) (13th August 1876 — 7th August 1942) was a Roman Catholic priest, Irish language scholar and Irish republican active in Sinn Féin, of which he was President in 1933–35.

Early life and education

Michael Flanagan was born on August 13th 1876 at Cloonfower, in the parish of Kilkeeven, close to Castlerea in County Roscommon. He was the second oldest son of Edward Flanagan (born 1842) and Mary Crawley (born 1847). Both of Michael's parents were fluent speakers in both Irish and English, living on a small farm in what was known as a breac or speckled gaeltacht. The family were supporters of the Fenian movement, and were members of the Land League. As a young man Michael was fascinated by politics and avidly followed the career of Parnell.[1]

Michael attended the local national school at Cloonboniffe, known as the Don School, and went on to attend secondary school at Summerhill College in Sligo. He entered St Patrick's College, Maynooth in the autumn of 1894 where he had an excellent academic record, winning prizes in theology, scripture, canon law, Irish language, education, and natural science.[2]

Michael Flanagan was ordained a priest of the Third Order of St. Francis for the Diocese of Elphin in Sligo Cathedral on 15th August 1900 at the age of 24. He returned to Summerhill College as Professor of Irish, a position he held until 1914, though he was away fundraising for long periods after 1904. While in Summerhill he published a well received booklet titled Irish Phonetics, on the pronunciation of the Irish language.

While working in Sligo Fr. O'Flanagan was active in his promotion of the Irish culture and language, and he gave evening language classes in Sligo Town Hall. He was a founding member of the organising committee of the Sligo Feis, which was first held in 1903. He was secretary of 1903 when P. H. Pearse was invited to give a lecture titled 'The Saving of a Nation' in Sligo Town Hall. Both Pearse and Douglas Hyde were the judges of the Irish language competitions in 1903 and again in 1904, so Fr. O'Flanagan knew both men well at this stage from his cultural activities.

Fundraising in the United States

Fr. O'Flanagan was a keen supporter rural development and Irish self-reliance, with a practical knowledge and point of view, having grown up on a small farm. He was a skilled public speaker and communicator and was vocal in agitating for radical social and political change. In 1904 he was invited by his Bishop John Joseph Clancy and Horace Plunkett to travel to the United States on a speaking and fundraising tour.

His mission was to promote Irish industry, in particular the lace industry, and to find investment and collect donations for agricultural and industrial projects in the west of Ireland. The diocese of Elphin had purchased the Dillon estate at Loughglynn in County Roscommon and had established a dairy industry there, managed by nuns of the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary. Part of Fr. O'Flanagan's brief was to pay off the outstanding debt on the venture.

Fr. O"Flanagan was an imaginative and innovative fundraiser; for example he brought a sod of every county in Ireland on his travels and charged people a dollar to step on their own native soil. He travelled with a small group of lace workers, who would give public demonstrations and show samples of various regional styles of Irish lace. Fr. O'Flanagan was an excellent publicist, and placed notices in regional newspapers to advertise the roadshow. He gave countless interviews and lectures on his travels and made many connections with the Irish American community.

He was to remain in the United States until 1910 when he was recalled to Ireland.

Gaelic League

In June of 1910 Fr. O'Flanagan returned to Ireland. In August, after attending a meeting he was elected to the executive of the Gaelic League. He reported 'the existence in every part of the States of an Irish population that is ever anxious to hear of home progress and to meet any representatives of any Irish movement'. Within a few weeks of his appointment to the standing committee the Gaelic League asked him to return to United States on another fundraising mission.

Along with Fionan McColum he travelled back to America to commence another round of fundraising. He went with the blessing of Bishop Clancy, who published a letter congratulating Fr. O'Flanagan on his selection. This mission was 'moderately successful' remitting £3,054 between March 1911 and July 1912. He returned to Ireland where Bishop Clancy appointed him curate in Roscommon in 1912. On the 19th of October Bishop Clancy died, and his successor, Dr. Bernard Coyne was a conservative who resented Fr. O'Flanagan's perceived modernism and independence.

In 1912 Fr. O'Flanagan was invited to Rome to give a series of lectures for Advent, and was a guest preacher in San Silvestro for four weeks. While in Rome he spent time with his good friend Dr. John Hagan who was director of the Irish College, and there is a large collection of letters between the two in the Hagan archive there[3]; Fr. O'Flanagan is often referred to as 'Brosna' in the letters.

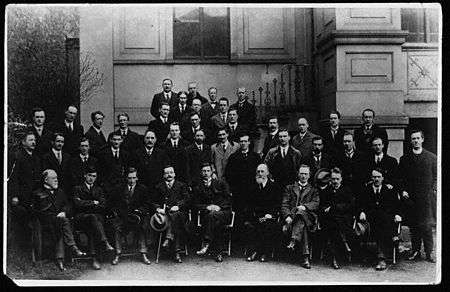

In 1913, the advanced nationalist Keating Branch took control of the Gaelic League and Fr. O'Flanagan was elected to the Standing Committee for two years. A recently discovered photograph shows Fr. O'Flanagan at a meeting of the Gaelic League outside Galway Town Hall in August of 1913.[4]

In 1914 Fr. O'Flanagan was invited back to Rome to give a series of Lenten lectures, and he spent six weeks, again preaching in San Silvestro's. At the end of his course of lectures he received a medal from the pope, Benedict XV. While preparing to leave Rome Fr. O'Flanagan was informed he was to be removed from Roscommon and was to proceed to Cliffoney in County Sligo.

Cliffoney

On 1 August 1914 the new bishop Bernard Coyne transferred Fr. Michael to Cliffoney, a small village in the parish of Ahamlish in north county Sligo. He had instructions from the bishop to assist the ailing priest, help the ailing lace industry in Cliffoney, and to look for land or a building for a village hall. Initially he rented a Lodge in Mullaghmore before eventually moving up to Cliffoney where he rented a cottage from Mrs. Hannan.[5]

While living in Cliffoney he actively campaigned against recruitment in the British army. Surviving letters indicate he was active in organising a company of Volunteers in Cliffoney. His sermons were noted down by the R.I.C. from the barracks next to the church who often occupied the front pew with notebooks to hand.[6] Fr. Michael condemned the export of food from the area, and demanded a fair and proper distribution of turbary rights. In newspaper pieces he contrasted Irish opinion-makers' outrage against Germany's contemporary treatment of Belgium with their indifference to England's ongoing treatment of Ireland.[7]

While in Cliffoney he discovered that the villagers were being denied access to the local bogs by the Congested Districts Board, a public body in charge of land redistribution. On Wednesday 30th June 1915 he led some 200 his parishioners up to Cloonerco bog where they commenced cutting turf, an incident which became known as 'The Cloonerco Bog Fight'. Eventually the locals in Cliffoney were granted access to the bogs.

.jpg)

At the end of July Fr. O'Flanagan was invited to speak at the funeral of the Fenian Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa.[8] He gave a speech at the Reception of the Remains in Dublin City Hall on the evening before the funeral. The following day he accompanied the family to Glasnevin Cemetery where Fr. O'Flanagan recited the final prayers in Irish by the graveside before Pearse made his famous speech.[9]

On October 9th 1915 Fr. O'Flanagan attended a meeting in Sligo court house chaired by canon Doorley, later Bishop of Elphin. A campaign was under way to encourage more tillage cultivation for the war effort. The main speaker was T. W. Russell, the vice president of the Board of Agriculture, who proposed a motion to that effect. Fr. O'Flanagan proposed a counter motion and went on to denounce the war and conscription. He said that Irish people should stay out of the war not of their making, and to raise plenty of crops to be kept at home to feed the many native people in want. His motion was ignored. His speech was reported in the local papers and recorded by the R.I.C.; the crown solicitor and District Inspector both attended the meeting.

Within days of the Sligo meeting Fr. O'Flanagan was transferred to Crossna, County Roscommon. The people of Cliffoney responded to his removal by locking the church, an incident which became known as the 'Cliffoney Rebellion'. On the morning of October 17th the key of the sacristy was taken; the door of the church was nailed shut and the new priest, Fr. C. McHugh was denied entry. The villagers began kneeling outside the church door each evening to say the Rosary for the return of Fr. O'Flanagan. They marched en masse into Sligo to interview the Bishop, who made himself absent. They went as far as sending a petition to the Pope, but to no avail. The bishop refused to back down, or to meet the villagers. Eventually the church was opened after ten weeks, when Fr. O'Flanagan appealed to the villagers to open the church for Christmas as a present to him. The door was unlocked on Christmas Eve 1915.

Crossna

On November 25th 1915, Fr. O'Flanagan delivered a lecture entitled 'God Save Ireland' to a packed audience in St. Mary's Hall, Belfast at a commemoration for the Manchester Martyrs. On January 1916 he took the train to Cork where he spoke to a monster crowd at an anti-conscription meeting chaired by Thomas MacCurtain—later assassinated by Crown forces—and policed by Terence MacSwiney who would die in 1920 after a long hunger strike.[10] Fr. O'Flanagan's fiery speech was recorded by the R.I.C. and widely reported in the press, and upon his return to Crossna he was sanctioned by Bishop Coyne, accused of making a speech disloyal to the Crown. He was forbidden to speak at public meetings or to spend a night outside the parish of Ardcarne without written permission from Bishop Coyne.

He also outraged nationalists in a letter to the Freeman's Journal in June 1916 when he discussed David Lloyd George's proposal to implement the 1914 Home Rule Act outside the six counties.[11]

The Election of the Snows

In December 1916 the Irish Parliamentary Party member for North Roscommon, the old fenian James O'Kelly died and his seat became vacant. A by-election was scheduled for February 1917 and Fr. O'Flanagan, grounded in North Roscommon took full advantage of the situation. Along with J. J. O'Kelly and P. J. Kehone, he proposed Count Plunkett as a candidate and they wrote to the Count inviting him to stand for North Roscommon. Fr. O'Flanagan, though forbidden to travel outside the boundaries of the parish, was largely instrumental in running the campaign which saw the Count take the seat by a large majority.[12]

In April of 1917 Count Plunkett summoned a Convention of advanced nationalists to meet at the Mansion House to seek common ground.

At the 1917 Sinn Féin convention, the Easter Rising veterans merged with Arthur Griffith's older organisation, with Éamon de Valera becoming president, and Griffith and O'Flanagan as vice presidents, for a three-year term. O'Flanagan proved a highly effective party manager. After the May 1918 German Plot, the majority of Sinn Féin leaders were interned or on the run, but Fr. O'Flanagan was exempted as a priest.

During the 1918 autumn general election campaign Fr. O'Flanagan toured the length and breadth of the country as one of the main public speakers addressing candidates and crowds. He was censored by the bishop but felt that it was essential to Ireland that East Cavan elect a Sinn Féin candidate. Nonetheless he became more queasy about the increasing level of violence deployed by the Irish Republican Army, and shrank from appearing with them in public.

The Sinn Féin candidates abstained from Westminster and instead proclaimed an Irish Republic with Dáil Éireann as its parliament. At the First Dáil's inauguration in January 1919, Fr. O'Flanagan was appointed as chaplain and opened proceedings with a prayer. On the Republic's Land Executive he was responsible for propaganda and agriculture in County Roscommon. By December 1920, with de Valera in the United States, O'Flanagan was acting president of the party. He also had talks with prime minister Lloyd George and found Dominion status for the Irish Free State acceptable.[13]

Republican Envoy

In December of 1920 Fr. O'Flanagan began a series talks with prime minister Lloyd George.[13] His critics, including Michael Collins who was conducting his own secret peace moves, accused him of waving a 'white flag'.

In late January 1921, during the Irish War of Independence, Fr. O'Flanagan and judge James O'Connor met informally in London with Sir Edward Carson to discuss a peaceful solution to the conflict, but without success.[14]

but when the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed in December 1921, O'Flanagan like his friend John J. O'Kelly was strongly opposed, and he left Ireland in fear of his life, arriving in the United States in November 1921. In 1923 he went to Australia and met the politically sympathetic Archbishop of Melbourne, Daniel Mannix, before being deported. He returned to Ireland from the United States in April 1925.

In March 1926, the Sinn Féin ard fheis narrowly defeated de Valera's proposal to enter the Free State Oireachtas if the Oath of Allegiance were removed. O'Flanagan sided with the majority. De Valera left to found Fianna Fáil, which eclipsed Sinn Féin at the June 1927 election. O'Flanagan remained with the reduced Sinn Féin. In 1925 he was suspended from clerical duties because of his nationalist activities and anti-clerical speeches he had made in America. Bishop Coyne died in July 1926, but the ban on his ministry remained in place, and he was never promoted in the hierarchy. He expressed brotherhood with union leader James Larkin and some Marxist sentiment but never joined any left-wing group, though he maintained his radical stance on social issues in the republican journal An Phoblacht.[11]

In later years he filed patents for protective goggles and house insulation products.

Father O'Flanagan undertook academic work at this time, editing for publication in 1927–8 many volumes of the 1830's letters by John O'Donovan in Ordnance Survey of Ireland notebooks. In the 1930's he was commissioned by the government to write a series of county histories of the Irish language for schools; five of the ten parts were published in his lifetime.

He was elected president of Sinn Féin from October 1933 to 1935. Brian O'Higgins resigned from the party in protest at O'Flanagan's presidency.[13] In 1936 he was expelled from Sinn Féin by the purists in the party because he took part in a radio re-enactment of the opening of the First Dáil, and recounted the part he had played in organising it.

He sympathised with Italian fascists when they invaded Abyssinia because they were enemies of Britain. He was one of the only Irish Catholic priests to defend the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War.[15]

On 3 April 1939, after much lobbying by his friends and supporters, he was restored to his full faculties by the Bishop of Elphin, Dr. Edward Doorly. In retirement he moved to Dublin, and acted as chaplain of two convents and a hospital.

After a short illness he died in a Dublin nursing home of stomach cancer on 7 August 1942. He was given a state funeral, when 21,000 people visited City Hall to pay their respects. His funeral was attended by deValera. He is buried in the Republican Plot in Glasnevin Cemetery, between Maude Gonne MacBride and Austin Stack. A memorial was placed on his grave by the National Graves Association in 1992.

References

- ↑ Carroll, Denis (1998). Unusual Suspects. The Columba Press. p. 206. ISBN 1-85607-239-8.

- ↑ Carroll, Denis (2016). They Have Fooled You Again. The Columba Press. ISBN 978-1-78218-300-6.

- ↑ Hagan, John. "Papers of John Hagan" (PDF). Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Siggins, Lorna (9 December 2013). "1916 signatories and three presidents identified in century-old photograph". The Irish Times.

- ↑ O'Flanagan, Michael (2017). From Cliffoney to Crosna. privately published. p. 7.

- ↑ Waters, Maureen (2001). Crossing Highbridge. Syracuse University Press. p. 142. ISBN 0-8156-0682-6.

- ↑ The Spark {{http://www.limerickcity.ie/media/spark,%202,%2051.pdf}}

- ↑ Century Ireland. [{http://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/enormous-crowds-attend-funeral-of-odonovan-rossa} 'Enormous crowds attend funeral of O’Donovan Rossa'], Dublin, 1 August 1915.

- ↑ Carroll, Denis. They Have Fooled You Again. The Columba Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-78218-300-6.

- ↑ "NOT IN THE NEWS: JANUARY 9-15, 1916". The Irish Revolution. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- 1 2 Murray, Patrick (2004). "O'Flanagan, Michael (1876–1942)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Farry, Michael (2012). The Irish Revolution, 1912-1923 Sligo. Four Courts Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-84682-302-2.

- 1 2 3 Dictionary of Irish National Biography

- ↑ "Memorandum by James O'Connor of an interview with Edward Carson from James O'Connor". Documents on Irish Foreign Policy. Royal Irish Academy. January 1921. No. 129 UCDA P150/1902. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Ó Conluain, Proinsias (17 October 1976). "The Staunchest Priest". Documentary on One. RTÉ Radio 1. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by ? Jennie Wyse Power (1911–) |

Vice-President of Sinn Féin 1917–1923 With: Arthur Griffith (1917–1922) |

Succeeded by Kathleen Lynn P. J. Ruttledge |

| Preceded by Brian O'Higgins |

Leader of Sinn Féin 1933–1935 |

Succeeded by Cathal Ó Murchadha |