Measles vaccine

.jpg) A child is given a measles vaccine. | |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | Measles |

| Type | Attenuated virus |

| Clinical data | |

| MedlinePlus | a601176 |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| | |

Measles vaccine is a vaccine that prevents measles.[1] After one dose 85% of children nine months of age and 95% over twelve months of age are immune.[2] Nearly all of those who do not develop immunity after a single dose develop it after a second dose.[1] When rates of vaccination within a population are greater than ~92% outbreaks of measles typically no longer occur; however, they may occur again if rates of vaccination decrease.[1] The vaccine's effectiveness lasts many years.[1] It is unclear if it becomes less effective over time.[1] The vaccine may also protect against measles if given within a couple of days of exposure to measles.[1]

The vaccine is generally safe including in those with HIV infections.[1] Side effects are usually mild and short lived.[1] This may include pain at the site of injection or mild fever.[1] Anaphylaxis has been documented in about 3.5–10 cases per million doses.[1] Rates of Guillain–Barré syndrome, autism and inflammatory bowel disease do not appear to be increased.[1]

The vaccine is available both by itself and in combination with other vaccines. This includes with the rubella vaccine and mumps vaccine to make the MMR vaccine,[1] first made available in 1971.[3] The addition of the varicella vaccine against chickenpox to these three in 2005 gave the MMRV vaccine.[4] The vaccine works equally well in all formulations.[1] The World Health Organization recommends it be given at nine months of age in areas of the world where the disease is common, or at twelve months where the disease is not common.[1] It is a vaccine based on a live but weakened strain of measles.[1] It comes as a dried powder which is mixed with a specific liquid before being injected either just under the skin or into a muscle.[1] Verification that the vaccine was effective can be determined by blood tests.[1]

About 85% of children globally have received this vaccine as of 2013.[5] In 2015, at least 160 countries provided two doses in their routine immunization.[6] It was first introduced in 1963.[2] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[7] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about 0.70 USD per dose as of 2014.[8]

Medical uses

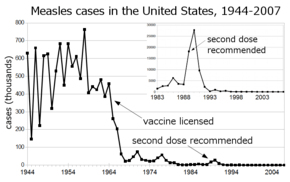

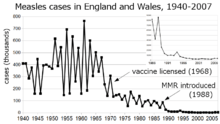

Before the widespread use of the measles vaccine, measles was so common that infection was felt to be "as inevitable as death and taxes."[9] In the United States, reported cases of measles fell from hundreds of thousands to tens of thousands per year following introduction of the vaccine in 1963 (see chart at right). Increasing uptake of the vaccine following outbreaks in 1971 and 1977 brought this down to thousands of cases per year in the 1980s. An outbreak of almost 30,000 cases in 1990 led to a renewed push for vaccination and the addition of a second vaccine to the recommended schedule. Fewer than 200 cases were reported each year from 1997 to 2013, and the disease was believed no longer endemic in the United States.[10][11][12] In 2014, 610 cases were reported.[13] Roughly 30 cases were diagnosed in January 2015, likely originating from exposure near Anaheim, California in late December 2014.

The benefit of measles vaccination in preventing illness, disability, and death have been well documented. The first 20 years of licensed measles vaccination in the U.S. prevented an estimated 52 million cases of the disease, 17,400 cases of mental retardation, and 5,200 deaths.[14] During 1999–2004, a strategy led by the World Health Organization and UNICEF led to improvements in measles vaccination coverage that averted an estimated 1.4 million measles deaths worldwide.[15] The vaccine for measles has led to the near-complete elimination of the disease in the United States and other developed countries.[16] While the vaccine is made with a live virus which can cause side effects, these are far fewer and less serious than the sickness and death caused by measles itself. While preventing many deaths and serious illnesses, the vaccine does cause side effects in a small percentage of recipients, ranging from rashes to, rarely, convulsions.[17]

Measles is common worldwide. Although it was declared eliminated from the U.S. in 2000, high rates of vaccination and excellent communication with those who refuse vaccination are needed to prevent outbreaks and sustain the elimination of measles in the U.S.[18] Of the 66 cases of measles reported in the U.S. in 2005, slightly over half were attributable to one unvaccinated individual who acquired measles during a visit to Romania.[19] This individual returned to a community with many unvaccinated children. The resulting outbreak infected 34 people, mostly children and virtually all unvaccinated; 9% were hospitalized, and the cost of containing the outbreak was estimated at $167,685. A major epidemic was averted due to high rates of vaccination in the surrounding communities.[18]

The vaccine has non specific effects such as preventing respiratory infections that may be greater than those of measles prevention. These benefits were greater when used before a year of age. A high titre vaccine resulted in worse outcomes in girls and thus is no longer recommended by the World Health Organization.[20] As measles causes upper respiratory disease that leads to complications of pneumonia and bronchitis, measles vaccine is beneficial to reduce exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma.

Schedule

The World Health Organization recommends two doses of vaccine for all children.[1] In countries with high risk of disease the first dose should be given around nine months of age.[1] Otherwise it can be given at twelve months of age.[1] The second dose should be given at least one month after the first dose.[1] This is often done at age 15 to 18 months.[1]

In the US, the CDC recommends that children aged 6 to 12 months traveling outside the United States receive their first dose of MMR vaccine.[21] Otherwise the first dose is typically given between 12–18 months. A second dose is given by 7 years (on or before last day of year 6) or by Kindergarten entry.[22] Vaccine is administered in the outer aspect of the upper arm. In adults, it is given subcutaneously and a second dose 28 days apart is given. In adults greater than 50 years, only one dose is needed.

Adverse effects

Adverse effects associated with the MMR vaccine include fever, injection site pain and, in rare cases, red or purple discolorations on the skin known as thrombocytopenic purpura, or seizures related to fever (febrile seizure).[23]

Numerous studies have shown that the MMR vaccine does not cause autism.[24][25][26][27][28]

Contraindications

History

As a fellow at Children's Hospital Boston, Thomas C. Peebles worked with John Franklin Enders. Enders became known as "The Father of Modern vaccines", and Enders shared the Nobel Prize in 1954 for his research on cultivating the polio virus that led to the development of a vaccination for the disease. Switching to study measles, Enders sent Peebles to Fay School in Massachusetts, where an outbreak of the disease was under way, and there Peebles was able to isolate the virus from some of the blood samples and throat swabs he had taken from the students. Even after Enders had taken him off the study team, Peebles was able to cultivate the virus and show that the disease could be passed on to monkeys inoculated with the material he had collected.[16] Enders was able to use the cultivated virus to develop a measles vaccine in 1963 based on the material isolated by Peebles.[31] In the late 1950s and early 1960s, nearly twice as many children died from measles as from polio.[32] The vaccine Enders developed was based on the Edmonston strain of attenuated live measles virus, which was named for the Fay student from whom Peebles had taken the culture that led to the virus's cultivation.[33]

In the mid-20th century, measles was particularly devastating in West Africa, where child mortality rates were 50 percent before age 5, and the children were struck with the type of rash and other symptoms common prior to 1900 in England and other countries. The first trial of a live attenuated measles vaccine was undertaken in 1960 by David Morley in a village near Ilesha, Nigeria; in case he could be accused of exploiting the Nigerian population, Morley included his own four children in the study. The encouraging results led to a second study of about 450 children in the village and at the Wesley Guild Hospital in Ilesha. Following another epidemic, a larger trial was undertaken in September and October 1962 in New York City with the assistance of the World Health Organization: 131 children received the live Enders attenuated Edmonston B strain plus gamma globulin, 130 children received a "further attenuated" vaccine without gamma globulin, and 173 children acted as control subjects for both groups. As also shown in the Nigerian trial, the trial confirmed that the "further attenuated" vaccine was superior to the Edmonston B vaccine, and caused significantly fewer instances of fever and diarrhea. The successful results led to 2,000 children in the area being vaccinated.[34][35]

Maurice Hilleman at Merck & Co., a pioneer in the development of vaccinations, developed the MMR vaccine in 1971, which treats measles, mumps and rubella in a single shot followed by a booster.[17][36] One form is called "Attenuvax".[37] The measles component of the MMR vaccine uses Attenuvax, which is grown in a chick embryo cell culture using the Enders' attenuated Edmonston strain. Merck decided not to resume production of Attenuvax on October 21, 2009.[38]

Types

Measles is seldom given as an individual vaccine and is often given in combination with rubella, mumps, or varicella.

- Measles vaccine (standalone vaccine)

- Measles rubella vaccine (MR vaccine)

- Mumps measles rubella vaccine, live (MMR vaccine)

- Mumps measles rubella and varicella virus vaccine (MMRV vaccine)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 World Health Organization (28 April 2017). "Measles vaccines: WHO position paper – April 2017" (PDF). Weekly epidemiological record (in English and French). No 17, 2017, 92: 205–228. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 September 2017.

- 1 2 Control, Centers for Disease; Prevention (2014). CDC health information for international travel 2014 the yellow book. p. 250. ISBN 9780199948505. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ "Vaccine Timeline". Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ↑ Mitchell, Deborah (2013). The essential guide to children's vaccines. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 127. ISBN 9781466827509. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ "Measles Fact sheet N°286". who.int. November 2014. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ "Immunization coverage". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2017-07-13. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Vaccine, Measles". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ↑ Babbott FL Jr; Gordon JE (1954). "Modern measles". Am J Med Sci. 228 (3): 334–61. PMID 13197385.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Summary of notifable diseases—United States, 1993 Archived 2010-03-09 at the Wayback Machine. Published October 21, 1994 for Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 1993; 42 (No. 53)

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Summary of notifable diseases—United States, 2007 Archived 2010-03-09 at the Wayback Machine. Published July 9, 2009 for Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2007; 56 (No. 53)

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Archived 2011-04-10 at the Wayback Machine.. Atkinson W, Wolfe S, Hamborsky J, McIntyre L, eds. 11th ed. Washington DC: Public Health Foundation, 2009

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-02-13. Retrieved 2015-02-14.

- ↑ Bloch AB, Orenstein WA, Stetler HC, et al. (1985). "Health impact of measles vaccination in the United States". Pediatrics. 76 (4): 524–32. PMID 3931045.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2006). "Progress in reducing global measles deaths, 1999–2004". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 55 (9): 247–9. PMID 16528234. Archived from the original on 2007-10-16.

- 1 2 Martin, Douglas. "Dr. Thomas C. Peebles, Who Identified Measles Virus, Dies at 89" Archived 2017-02-13 at the Wayback Machine., The New York Times, August 4, 2010. Accessed August 4, 2010.

- 1 2 Collins, Huntly. "The Man Who Saved Your Life - Maurice R. Hilleman - Developer of Vaccines for Mumps and Pandemic Flu: Maurice Hilleman's Vaccines Prevent Millions of Deaths Every Year" Archived 2009-03-06 at the Wayback Machine., copy of article from The Philadelphia Inquirer, August 30, 1999. Accessed August 4, 2010.

- 1 2 Parker AA, Staggs W, Dayan GH, et al. (2006). "Implications of a 2005 measles outbreak in Indiana for sustained elimination of measles in the United States". N Engl J Med. 355 (5): 447–55. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060775. PMID 16885548.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2006). "Measles—United States, 2005". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 55 (50): 1348–51. PMID 17183226. Archived from the original on 2015-03-13.

- ↑ Sankoh O, Welaga P, Debpuur C, Zandoh C, Gyaase S, Poma MA, Mutua MK, Hanifi SM, Martins C, Nebie E, Kagoné M, Emina JB, Aaby P (2014). "The non-specific effects of vaccines and other childhood interventions: the contribution of INDEPTH Health and Demographic Surveillance Systems". Int J Epidemiol. 43 (3): 645–53. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu101. PMC 4052142. PMID 24920644.

- ↑ "Measles and the Vaccine (Shot) to Prevent It". Centers for Disease Control. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ Washington Stat Dept of Health

- ↑ Demicheli V, Rivetti A, Debalini MG, Di Pietrantonj C (2012). "Vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2: CD004407. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004407.pub3. PMID 22336803.

- ↑ https://www.nap.edu/read/13164/chapter/6#152

- ↑ "Measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008-08-22. Archived from the original on 2008-10-08. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ↑ Immunization Safety Review: Vaccines and Autism Archived 2007-06-23 at the Wayback Machine.. From the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences. Report dated May 17, 2004; accessed June 13, 2007.

- ↑ MMR Fact Sheet Archived 2007-06-15 at the Wayback Machine., from the United Kingdom National Health Service. Accessed June 13, 2007.

- ↑ Demicheli V, Rivetti A, Debalini MG, Di Pietrantonj C (2012). "Vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2: CD004407. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004407.pub3. PMID 22336803.

- ↑ Guidelines for Vaccinating Pregnant Women Archived 2014-10-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Chart of Contraindications and Precautions to Commonly Used Vaccines Archived 2014-12-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Staff. "Work by Enders Brings Measles Vaccine License" Archived 2012-11-03 at the Wayback Machine., The Hartford Courant, March 22, 1963. Accessed August 4, 2010. "A strain of measles virus isolated in 1954 by Dr. Thomas C. Peebles, instructor in pediatrics at Harvard, and Enders, formed the basis for the development of the present vaccine".

- ↑ Staff. "The Measles Vaccine" Archived 2014-02-19 at the Wayback Machine., The New York Times, March 28, 1963. Accessed August 4, 2010.

- ↑ Hilleman, Maurice R. "Past, Present, and Future of Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Virus Vaccines", Pediatrics (journal), Vol. 90 No. 1 July 1992, pp. 149-153. Accessed August 4, 2010.

- ↑ Morley, David. C. (1964). "Measles and Measles Vaccination in an African Village" (PDF). Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 30: 733–739. PMC 2554995. PMID 14196817. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ↑ Pritchard, John (13 November 1997). "Obituary: Dr C. A. Pearson". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ↑ Sullivan, Patricia (2005-04-13). "Maurice R. Hilleman Dies; Created Vaccines (washingtonpost.com)". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ↑ Ovsyannikova IG, Johnson KL, Naylor S, Poland GA (February 2005). "Identification of HLA-DRB1-bound self-peptides following measles virus infection". J. Immunol. Methods. 297 (1–2): 153–67. doi:10.1016/j.jim.2004.12.020. PMID 15777939.

- ↑ Q & As about Monovalent M-M-R Vaccines Archived 2012-05-15 at the Wayback Machine.