Mathias Rust

| Mathias Rust | |

|---|---|

|

Rust in 2012 | |

| Born |

1 June 1968 Wedel, Schleswig-Holstein, West Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Illegally landing a small aircraft on Moscow's Red Square. |

Mathias Rust (born 1 June 1968) is a German aviator known for his illegal landing near Red Square in Moscow on 28 May 1987. An amateur pilot, the teenager flew from Helsinki, Finland, to Moscow, being tracked several times by Soviet air defence and interceptors. The Soviet fighters never received permission to shoot him down, and several times his aeroplane was mistaken for a friendly aircraft. He landed on Vasilevsky Descent next to Red Square near the Kremlin in the capital of the Soviet Union.

Rust said he wanted to create an "imaginary bridge" to the East, and he has said that his flight was intended to reduce tension and suspicion between the two Cold War sides.[1][2]

Rust's flight through a supposedly impenetrable air defence system had great effect on the Soviet military and led to the dismissal of many senior officers, including Minister of Defence Marshal of the Soviet Union Sergei Sokolov and the Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Air Defence Forces, former World War II fighter ace pilot Chief Marshal Alexander Koldunov. The incident aided Mikhail Gorbachev in the implementation of his reforms, by allowing him to dismiss numerous military officials opposed to his policies. Rust was sentenced to four years in prison (for violation of border crossing and air traffic regulations, and provoking an emergency situation upon his landing). He was officially pardoned by the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet Andrei Gromyko, and released after 14 months in prison.[1][2]

Flight profile

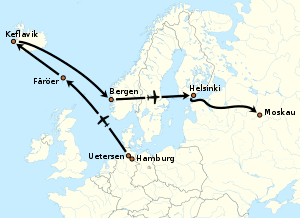

Rust, aged 18, was an inexperienced pilot, with about 50 hours of flying experience at the time of his flight. On 13 May 1987, Rust left Uetersen near Hamburg and his home town Wedel in his rented Reims Cessna F172P D-ECJB, which was modified by removing some of the seats and replacing them with auxiliary fuel tanks. He spent the next two weeks travelling across Northern Europe, visiting the Faroe islands, spending a week in Iceland, and then visiting Bergen on his way back. He was later quoted as saying that he had the idea of attempting to reach Moscow even before the departure, and he saw the trip to Iceland (where he visited Hofdi House, the site of unsuccessful talks between the United States and the Soviet Union in October 1986) as a way to test his piloting skills.[1]

On the morning of 28 May 1987, Rust refuelled at Helsinki-Malmi Airport. He told air traffic control that he was going to Stockholm, and took off at 12:21 p.m. Immediately after his final communication with traffic control he turned his plane to the east near Nummela. Air traffic controllers tried to contact him as he was moving around the busy Helsinki–Moscow route, but Rust turned off all his communications equipment.[1][3]

Rust disappeared from the Finnish air traffic radar near Espoo.[1] Control personnel presumed an emergency and a rescue effort was organized, including a Finnish Border Guard patrol boat. They found an oil patch near Sipoo where Rust disappeared from radar, and performed an underwater search with no results.

Rust crossed the Baltic coastline over Estonia and turned towards Moscow. At 14:29 he appeared on Soviet Air Defence Forces (PVO) radar and, after failure to reply to an IFF signal, was assigned combat number 8255. Three SAM battalions of 54th Air Defence Corps tracked him for some time, but failed to obtain permission to launch at him.[4] All air defences were brought to readiness and two interceptors were sent to investigate. At 14:48 near Gdov one of the pilots observed a white sport plane similar to a Yakovlev Yak-12 and asked for permission to engage, but was denied.[1]

The fighters lost contact with Rust soon after this. While they were being directed back to him he disappeared from radar near Staraya Russa. West German magazine Bunte speculated that he might have landed there for some time, noting that he changed his clothes during his flight and that he took too much time to fly to Moscow considering his plane's speed and the weather conditions.

Air defence re-established contact with Rust's plane several times but confusion followed all of these events. The PVO system had shortly before been divided into several districts, which simplified management but created additional overhead for tracking officers at the districts' borders. The local air regiment near Pskov was on maneuvers and, due to inexperienced pilots' tendency to forget correct IFF designator settings, local control officers assigned all traffic in the area friendly status, including Rust.[1]

Near Torzhok there was a similar situation, as increased air traffic was created by a rescue effort for an air crash the previous day. Rust, flying a slow propeller-driven aircraft, was confused with one of the helicopters taking part in the rescue. He was spotted several more times and given false friendly recognition twice. Rust was considered as a domestic training plane defying regulations, and was issued least priority.[1]

Around 7:00 p.m. Rust appeared above Moscow. He had initially intended to land in the Kremlin, but he reasoned that landing inside, hidden by the Kremlin walls, would have allowed the KGB to arrest him and deny the incident. Therefore, he changed his landing spot to Red Square.[1] Heavy pedestrian traffic did not allow him to land there either, so after circling about the square one more time, he was able to land on Bolshoy Moskvoretsky Bridge by St. Basil's Cathedral. A later inquiry found that trolleybus wires normally strung over the bridge—which would have prevented his landing there—had been removed for maintenance that morning, and were replaced the next day.[1] After taxiing past the cathedral he stopped about 100 metres (330 ft) from the square, where he was greeted by curious passersby and was asked for autographs. When asked where he was from, he replied "Germany" making the bystanders think he was from East Germany; but when he said West Germany, they were surprised.[5] A British doctor videotaped Rust circling over Red Square and landing on the bridge.[5] Rust was arrested two hours later.[6]

Aftermath

Rust's trial began in Moscow on 2 September 1987. He was sentenced to four years in a general-regime labour camp for hooliganism, for disregard of aviation laws, and for breaching the Soviet border.[7] He was never transferred to a labour camp, and instead served his time at the high security Lefortovo temporary detention facility in Moscow. Two months later, Reagan and Gorbachev agreed to sign a treaty to eliminate intermediate-range nuclear weapons in Europe, and the Supreme Soviet ordered Rust to be released in August 1988 as a goodwill gesture to the West.[1]

Rust's return to Germany on 3 August 1988 was accompanied by huge media attention, but he did not talk to the assembled journalists; his family had sold the exclusive rights to the story to the German magazine Stern for DM 100,000.[5] He reported that he had been treated well in the Soviet prison. Journalists described him as "psychologically unstable and unworldly in a dangerous manner".[5]

William E. Odom, former director of the U.S. National Security Agency and author of The Collapse of the Soviet Military, says that Rust's flight irreparably damaged the reputation of the Soviet military. This enabled Gorbachev to remove many of the strongest opponents to his reforms. Minister of Defence Sergei Sokolov and the head of the Soviet Air Defence Forces Alexander Koldunov were dismissed along with hundreds of other officers. This was the biggest turnover in the Soviet military since Stalin's purges 50 years earlier.[1][8]

Rust's rented Reims Cessna F172P (serial #F17202087),[9] registered D-ECJB, was sold to Japan where it was exhibited for several years. In 2008 it was returned to Germany and was placed in the Deutsches Technikmuseum in Berlin.[10][11]

Later life

While doing his obligatory community service (Zivildienst) in a West German hospital in 1989, Rust stabbed a female co-worker who had rejected him. The victim barely survived. He was convicted of attempted manslaughter and sentenced to two and a half years in prison, but was released after 15 months.[12] Since then he has lived a fragmented life, describing himself as a "bit of an oddball."[13] After being released from court, he converted to Hinduism in 1996 to become engaged to a daughter of an Indian tea merchant.[14] In 2001, he was convicted of stealing a cashmere pullover and ordered to pay a fine of DM 10,000, which was later reduced to DM 600.[5][12] A further brush with the law came in 2005, when he was convicted of fraud and had to pay €1,500 for stolen goods.[12] In 2009 Rust described himself as a professional poker player.[15] Most recently, in 2012, he described himself as an analyst at a Zurich-based investment bank.[13]

Peace activism

In October 2015, The Hindu published an interview with Mathias Rust to mark the 25th anniversary of German reunification. Mathias Rust surmised that institutional failures in Western countries to preserve moral standards and uphold the primacy of democratic ideals was creating mistrust between peoples and governments. Pointing to the genesis of a New Cold War between Russia and the Western powers, Mathias Rust suggested that India should tread with caution and avoid entanglement: "India will be better served if it follows a policy of neutrality while interacting with EU member countries as the big European powers at present are following the foreign policy of the U.S. unquestioningly". Mathias Rust drew attention to the casus belli which is fuelling Euroscepticism: "Governments have been dominated by the corporate entities and citizens have ceased to matter in public policy".[16][17]

In popular culture

Because Rust's flight seemed like a blow to the authority of the Soviet regime, it was the source of numerous jokes and urban legends. For a while after the incident, Red Square was jokingly referred to by Muscovites as Sheremetyevo-3 (Sheremetyevo-1 and -2 being the two terminals at Moscow's main international airport).[18] At the end of 1987, the police radio code used by law enforcement officers in Moscow was allegedly updated to include a code for an aircraft landing.[19]

Shortly after the incident, SubLogic, the original publishers of the Flight Simulator franchise, issued a scenery disk that expanded the original program's coverage area to include the Eastern Bloc. A challenge in the expansion pack was to land in Red Square as Rust had just done.[20]

In the media

Following the 20th anniversary of his flight on 28 May 2007, the international media interviewed Rust about the flight and its aftermath.

The Washington Post and Bild both have online editions of their interviews.[21] The most comprehensive televised interview available online is produced by the Danish Broadcasting Corporation. In their interview Rust in Red Square, recorded in May 2007, Rust gives a full account of the flight in English.[22]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 LeCompte, Tom (July 2005). "The Notorious Flight of Mathias Rust". Air & Space/Smithsonian. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- 1 2 Hadjimatheou, Chloe (7 December 2012). "Mathias Rust: German teenager who flew to Red Square". BBC World Service. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ↑ coptercrazy (n.d.). "Listing of Production Reims F172". Archived from the original on 14 March 2005. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ↑ Khodarenok, Mikhail (28 May 2017). "Руста прикрыли облака" [Rust hidden by clouds]. Gazeta.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Locke, Stefan (12 May 2012). "Der lange Irrflug der Friedenstaube" [The long erratic flight of the peace dove]. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Frankfurt. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ↑ Rehrmann, Marc-Oliver (26 June 2009). "Der Kremlflieger Mathias Rust kehrt zurück" [The Kremlin Flyer Mathias Rust returns] (in German). Hamburg: Norddeutscher Rundfunk. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ↑ Barringer, Felicity (9 December 1987). "German in Red Square Flight Is Denied a Pardon". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ↑ Brown, A. (2007). "Perestroika and the End of the Cold War". Cold War History. 7: 1. doi:10.1080/14682740701197631.

- ↑ Deutsches Technikmuseum (14 May 2009), Cessna F 172 P „Skyhawk II", retrieved 18 October 2012

- ↑ Reims Cessna F172P, D-ECJB, in the Deutsches Technikmuseum, 2009 Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ Himmelfahrt zum Roten Platz – Deutsches Technikmuseum zeigt Cessna 172, mit der Mathias Rust 1987 in Moskau landete

- 1 2 3 Krüger, Ralf E.; Grages, Anna (25 May 2007). "Moskau-Flug: Der Kremlflieger pokert hoch" [The Kremlin Flyer raises the stakes]. Westdeutsche Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- 1 2 Connolly, Kate (14 May 2012). "German who flew to Red Square during cold war admits it was irresponsible". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ↑ Connolly, Kate (21 April 2001). "German daredevil grounded by court". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ↑ "Kreml-Flieger Rust: "750.000 Euro beim Pokern gewonnen"" [Kremlin Flyer Rust: "I won 750,000 Euros playing poker"]. Spiegel Online (in German). 6 June 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ "contributed to ending the Cold War, with his daring". The Hindu. 4 October 2015.

- ↑ "The Teenage Pilot Who Could Have Caused a Global Crisis". Time. 28 May 2015.

- ↑ Bushansky, Valentin (28 May 2008). "10 фактов о Матиасе Русте ко Дню пограничника" [10 Facts about Mathias Rust on Border Guard's Day] (in Russian). Fraza. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ↑ Милицейские байки. 15-й десяток (in Russian).

- ↑ "Scenery Disk "Western European Tour"". MobyGames. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ Finn, Peter (27 May 2007). "A Dubious Diplomat". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ↑ Mathias Rust INTERVIEW on YouTube

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mathias Rust. |

- Excerpts of video capturing Rust's flying and landing in Moscow

- Rust in Red Square (English) about the flight and the aftermath. Interview clips are embedded in a flash presentation. (October 2007)

- TV Interview 2007 on YouTube English interview in Danish news cast eng/eng subs (28 May 2007)

- Smithsonian's Air & Space Magazine: "The Notorious Flight of Mathias Rust" Comprehensive article about the flight and the political aftermath in Gorbachev's USSR (1 July 2005)

- Guardian: interview with Mathias Rust

- Where Are They Now?: Mathias Rust

- The Cessna, registration number D-ECJB on display Deutsches Technikmuseum, Berlin

- Novaya Gazeta: РУСТ — ЭТО ПО-НАШЕМУ

- Washington Post: A Dubious Diplomat Washington Post article on Rust incident, aftermath, and Rust's life today. (27 May 2007)

- Mathias Rust, fly to the heart of USSR, by Jose Antonio Lozano (in Spanish)

- Danmarks Radio - "Rust in Red Square" interview, May 2007

- Mathias Rust on IMDb

- BBC article including original video of the landing.

- Mathias Rust Interview from the Love + Radio podcast