Mask of Agamemnon

| Mask of Agamemnon | |

|---|---|

The mask in its current location | |

| Material | Gold |

| Created | 1550–1500 B.C. |

| Discovered | 1876 at Mycenae, Greece by Heinrich Schliemann |

| Present location | National Archaeological Museum, Athens |

The Mask of Agamemnon is a gold funeral mask discovered at the ancient Greek site of Mycenae. The mask, displayed in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, has been described by Cathy Gere as the "Mona Lisa of prehistory".[1]

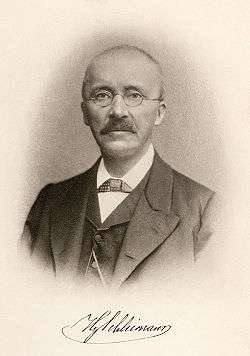

German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann, who discovered the artifact in 1876, believed that he had found the body of the Mycenean king Agamemnon, leader of the Achaeans in Homer's epic of the Trojan War, the Iliad, but modern archaeological research suggests that the mask predates the period of the legendary Trojan War by about 300 years.

Discovery

German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann found the mask in 1876[2] in a burial shaft designated Grave V at the site "Grave Circle A, Mycenae".[3] The mask is one of five discovered in the royal shaft graves at Mycenae—three in Grave IV and two in Grave V. The faces and hands of two children in Grave III are covered with gold leaf, one covering having holes for the eyes. The mask was designed to be a funeral mask covered in gold.

The faces of the men are not all covered with masks. That they are men and warriors is suggested by the presence of weapons in their graves. The quantities of gold and carefully worked artifacts indicate honor, wealth and status. The custom of clothing leaders in gold leaf is known elsewhere. The Mask of Agamemnon was named by Schliemann after the legendary Greek king of Homer's Iliad. This mask adorned one of the bodies in the shaft graves at Mycenae. Schliemann took this as evidence the Trojan War was a real historical event.

The mask of Agamemnon was created from a single thick gold sheet, heated and hammered against a wooden background with the details chased on later with a sharp tool.[4] Following his discoveries at the site, Schliemann notified King George of Greece.[5] He is supposed to have told the king in a telegraph, "I have gazed upon the face of Agamemnon".[6] Schliemann later named his son, Agamemnon Schliemann, after the legendary king.

Authenticity

In the later half of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, the authenticity of the mask has been formally questioned, primarily by William Calder III and David Traill.[7] Archaeology magazine has run a series of articles presenting both sides of the debate. By the time of the excavation of the Shaft Graves, the Greek Archaeological Society had taken a hand in supervising Schliemann's work (after the issues at Troy), sending Panagiotis Stamatakis as ephor, or director, of the excavation, who kept a close eye on Schliemann.

Proponents of the fraud argument center their case on Schliemann's reputation for salting digs with artifacts from elsewhere. The resourceful Schliemann, they assert, could have had the mask manufactured on the general model of the other Mycenaean masks and found an opportunity to place it in the excavation.

The defending advocate(s) point out that the excavation was closed on November 26–27 for Sunday holiday and rain. It was not allowed to reopen until Stamatakis had provided the work with credible witnesses. The three other masks were not discovered until the 28th. The Mask of Agamemnon was found on the 30th.

A second critique is based on style. The Mask of Agamemnon differs from three of the other masks in a number of points: it is three-dimensional rather than flat, one of the facial hairs is cut out, rather than engraved, the ears are cut out, the eyes are depicted as both open and shut, with open eyelids, but a line of closed eyelids across the center, the face alone of all the depictions of faces in Mycenaean art has a full pointed beard with handlebar mustache, the mouth is well-defined (compared to the flat masks), the brows are formed to two arches rather than one.

The defense presented prior arguments that the shape of the lip, the triangular beard and the detail of the beard are nearly the same as the mane and locks of the gold lion-head rhyton from Shaft Grave IV. Schliemann's duplicity, they claim, has been greatly exaggerated, and they also claim that the attackers were conducting a vendetta.

Modern archaeological research suggests that the mask is genuine but predates the period of the Trojan War by about 300 years.[8]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Gere 2011, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ "Behind the Mask of Agamemnon" by Spencer P.M. Harrington in Archaeology, Vol. 52, No. 4, July/August 1999. Online archive, retrieved 29 May 2013. Archived here.

- ↑ Gere 2011.

- ↑ Questioning The Mycenaean Death Mask Of Agamemnon

- ↑ Harrington, Spencer P.M.; Calder, William M.; Traill, David A.; Demarkopoulou, Katie; Lapatin, Kenneth D.S. (1999). "Behind the Mask of Agamemnon". Archaeology. 52 (4): 51–59. doi:10.2307/41779424. JSTOR 41779424.

- ↑ Dickinson, O. T. P. K. (2005). "The "Face of Agamemnon"". Hesperia. 74. pp. 299–308.

- ↑ Gere 2011, p. 176.

- ↑ "Behind the Mask of Agamemnon" by Spencer P.M. Harrington in Archaeology, Vol. 52, No. 4, July/August 1999. Online archive, retrieved 25 July 2018. Archived here.

References

- Gere, Cathy (2011). The Tomb of Agamemnon. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06824-7.

- Behind the mask of Agamemnon, July/August 1999

- Is the Mask a Hoax? op. cit.

- Insistent Questions op. cit.

- The Case for Authenticity op. cit.

- Not A Forgery. How about a Pastiche? op. cit.

- Epilogue op. cit.

- Questioning The Mycenaean Death Mask Of Agamemnon op. cit.