Mary Beard (classicist)

| Dame Mary Beard DBE FSA FBA | |

|---|---|

|

Beard in 2017 | |

| Born |

Winifred Mary Beard 1 January 1955 Much Wenlock, Shropshire, England |

| Awards |

|

| Academic background | |

| Education | Shrewsbury High School |

| Alma mater | Newnham College, Cambridge (MA, PhD) |

| Thesis | The state religion in the late Roman Republic: a study based on the works of Cicero (1982) |

| Doctoral advisor | John Crook |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Classics |

| Sub-discipline | |

| Institutions | |

| Notable works |

The Roman Triumph SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome |

Dame Winifred Mary Beard, DBE, FSA, FBA (born 1 January 1955)[1] is an English scholar and classicist. The New Yorker characterises her as "learned but accessible".[2]

Beard is Professor of Classics at the University of Cambridge,[3] a fellow of Newnham College, and Royal Academy of Arts Professor of Ancient Literature. She is the Classics editor of The Times Literary Supplement, where she also writes a regular blog, "A Don's Life".[4][5] Her frequent media appearances and sometimes controversial public statements have led to her being described as "Britain's best-known classicist."[6]

Beard was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in the 2018 Birthday Honours for services to the study of classical civilisations.[7]

Early life

Mary Beard, an only child, was born on 1 January 1955[8] in Much Wenlock, Shropshire. Her mother, Joyce Emily Beard, was a headmistress and an enthusiastic reader.[6][9] Her father, Roy Whitbread Beard,[9] worked as an architect in Shrewsbury. She recalled him as "a raffish public-schoolboy type and a complete wastrel, but very engaging".[6]

Beard was educated at Shrewsbury High School, a girls' school then funded as a direct grant grammar school.[10] She was taught poetry by Frank McEachran,[11] the inspiration for schoolmaster Hector in Alan Bennett's play The History Boys.[12] During the summer she would join archaeological excavations, though the motivation was, in part, just the prospect of earning some pocket-money.[8]

At eighteen she sat the then-compulsory entrance exam and interview for Cambridge University, to win a place at Newnham College, a single-sex college.[8] She had considered King's, but rejected it when she learned the college did not offer scholarships to women.[8]

In Beard's first year she found that some men in the university still held very dismissive attitudes regarding the academic potential of women, which only strengthened her determination to succeed.[13] She also developed feminist views that remained "hugely important" in her later life, although she later described "modern orthodox feminism" as partly cant.[6] Beard has since said that "Newnham could do better in making itself a place where critical issues can be generated" and has also described her views on feminism, saying "I actually can't understand what it would be to be a woman without being a feminist."[14] Beard has cited Germaine Greer's The Female Eunuch, Kate Millett's Sexual Politics, and Robert Munsch’s The Paper Bag Princess as influential on the development of her personal feminism.[15]

Beard graduated from Cambridge with a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree: as per tradition, her BA was later promoted to a Master of Arts (MA Cantab) degree.[16][17] She remained at Cambridge for her Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degree: she completed it in 1982 with a doctoral thesis titled The State Religion in the Late Roman Republic: A Study Based on the Works of Cicero.[9]

Career

Between 1979 and 1983, Beard lectured in Classics at King's College, London; she returned to Cambridge in 1984 as a Fellow of Newnham College and the only female lecturer in the Classics faculty.[6][9] Rome in the Late Republic, which she co-wrote with Cambridge historian Michael Crawford, was published the following year.[18]

John Sturrock, Classics editor of The Times Literary Supplement, approached her for a review and brought her into literary journalism.[19] Beard took over his role in 1992[9] at the request of Ferdinand Mount.[20] In 1994 she made an early television appearance on an Open Media discussion for the BBC, Weird Thoughts,[21] alongside Jenny Randles and James Randi among others.

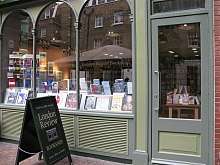

Shortly after the 11 September 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center, Beard was one of several authors invited to contribute articles on the topic to the London Review of Books. She opined that many people, once "the shock had faded", thought "the United States had it coming", and that "[w]orld bullies, even if their heart is in the right place, will in the end pay the price"[22]. In a November 2007 interview, she stated that the hostility these comments provoked had still not subsided, although she believed it had become a standard viewpoint that terrorism was associated with American foreign policy.[6] By this point she was described by Paul Laity of The Guardian as "Britain's best-known classicist".[6]

In 2004, Beard became Professor of Classics at Cambridge.[3][9] She was elected Visiting Sather Professor of Classical Literature for 2008–2009 at the University of California, Berkeley, where she delivered a series of lectures on "Roman Laughter".[23] In 2007–2008 Beard gave the Sigmund H. Danziger Jr. Memorial Lecture in the Humanities at the University of Chicago.[24]

In December 2010, on BBC Two, Beard presented Pompeii: Life and Death in a Roman Town, submitting remains from the town to forensic tests, aiming to show a snapshot of the lives of the residents prior to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE.[25] In 2011 she took part in a television series, Jamie's Dream School on Channel 4, in which she taught classics to teenagers with no experience of academic success. Beard is a regular contributor to the BBC Radio 4 series, A Point of View, delivering essays on a broad range of topics including Miss World[26] and the Oxbridge interview.[27]

For BBC Two in 2012 she wrote and presented the three part television series, Meet the Romans with Mary Beard, which concerns how ordinary people lived in Rome, "the world's first global metropolis". The critic A. A. Gill reviewed the programme, writing mainly about her appearance (teeth, hair, and clothes), judging her "too ugly for television".[28] Beard admitted that his attack felt like a punch,[29] but swiftly responded with a counter-attack on his intellectual abilities, accusing him of being part of "the blokeish culture that loves to decry clever women".[28] This exchange became the focus of a debate about older women on the public stage, with Beard saying she looked an ordinary woman of her age[30] and "there are kids who turn on these programmes and see there’s another way of being a woman", without Botox and hair dye.[31] Charlotte Higgins assessed Beard as one of the rare academics who is both well respected by her peers and has a high profile in the media.[32]

Beard is known for being active on Twitter, responding to critics and trolls with reason and optimism; she sees this as part of her public role as an academic.[33] Beard received considerable online abuse after she appeared on BBC's Question Time from Lincolnshire in January 2013 and cast doubt on the negative rhetoric about immigrant workers living in the county.[34][35] Beard used her blog to quote some of the abusive comments about her, and to reproduce (until the TLS took them down) the doctored images[36] ("pornographic, violent, sexist, misogynist and also frightfully silly") which no mainstream media would print or let her read aloud. She also reasserted her right to express unpopular opinions and to present herself in public in an authentic way.[37] On 4 August 2013, she received a bomb threat on Twitter, hours after the UK head of that social networking site had apologised to women who had experienced abuse on the service. Beard said she did not think she was in physical danger, but considered it harassment and wanted to "make sure" that another case had been logged by the police.[38] She has stood up to bullies and shone a light on "social media at its most revolting and misogynistic", bringing to wider public attention a problem that had previously not been much discussed in mainstream press.[30]

In 2013 she presented Caligula with Mary Beard, describing the making of myths around leaders and dictators.[39] Interviewers continued to ask about her self-presentation, and she reiterated that she had no intention of undergoing a make-over.[40]

On 14 February 2014 Beard delivered a lecture on the public voice of women at the British Museum as part of the London Review of Books winter lecture series. "Oh Do Shut Up, Dear!", shown on BBC Four a month later, started with the example of Telemachus, the son of Odysseus and Penelope, admonishing his mother to retreat to her chamber.[41] Three years later, Beard gave a second lecture for the same partners, entitled "Women in Power", from Medusa to Merkel. It considered the extent to which the exclusion of women from power is culturally embedded, and how idioms from ancient Greece are still used to normalise gendered violence.[42] She argues that "we don’t have a model or a template for what a powerful woman looks like. We only have templates that make them men."[43]

In December 2015, Beard was again a panelist on BBC's Question Time from Bath.[44] During the programme, she praised Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn for behaving with a "considerable degree of dignity" against claims he faces an overly hostile media. She said: "Quite a lot of what Corbyn says I agree with, and I rather like his different style of leadership. I like hearing argument not soundbites. If the Labour Party is going through a rough time, and I'm sure it is rough to be in there, it might actually all be to the good. He might be changing the party in a way that would make it easier for people like me to vote for."[45]

2016 saw Beard present Pompeii: New Secrets Revealed with Mary Beard on BBC One in March.[46] While May 2016, brought about a four-part series shown on BBC Two, titled Mary Beard's Ultimate Rome: Empire Without Limit.[47]

Beard's standalone documentary Julius Caesar Revealed was shown on BBC One in February 2018.[48] In March, she wrote and presented "How Do We Look?" and "The Eye of Faith", two of the nine episodes in Civilisations, a reboot of the 1969 series by Kenneth Clark.[49]

Approach to scholarship

According to University of Chicago classicist Clifford Ando, Beard is noted for two aspects of her approach to sources:

- she insists that ancient sources be understood as documentation of the attitudes, context and beliefs of their authors, not as reliable sources for the events they address

- she argues that modern histories of Rome be contextualised within the attitudes, world views and purposes of their authors.[50]

Honours

- Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries (FSA) in 2005[51]

- Wolfson History Prize (2008) for Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town[52]

- Fellow of the British Academy (FBA) in 2010[53]

- Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2013 New Year Honours for "services to classical scholarship"[54]

- National Book Critics Circle Award (Criticism) shortlist for Confronting the Classics (2013)[55][56]

- Bodley Medal (2016)[57]

- Princess of Asturias Award for Social Sciences (2016)[58]

- Honorary degree from the Charles III University of Madrid in 2017 [59]

- Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in the 2018 Birthday Honours for "services to the study of classical civilisations"[7]

In addition, in April 2013, she was named as Royal Academy of Arts professor of ancient literature, a largely honorary post.[60]

Public Controversies

In response to a Times report of Oxfam employees engaging in sexual exploitation in disaster zones, Mary Beard tweeted "Of course one can’t condone the (alleged) behaviour of Oxfam staff in Haiti and elsewhere. But I do wonder how hard it must be to sustain “civilised” values in a disaster zone. And overall I still respect those who go in and help out, where most of us would not tread." [61][62] This led to widespread criticism, in which Mary Beard was accused of racism.[62] In response, Mary Beard posted a picture of herself crying.[63][64] Fellow Cambridge academic, Priyamvada Gopal, referred to Mary Beard's tweet and subsequent blog post as "genteel and patrician casual racism."[65] Mary Beard's use of a tearful photo was branded as 'manipulative' and she was accused of shedding 'white feminist tears'.[63][64][66]

Personal life

Beard married Robin Cormack, a classicist and art historian, in 1985. Their daughter Zoe is a historian of South Sudan and their son Raphael is a scholar of Egyptian literature.[2]

In 2000, Beard revealed in an essay reviewing a book on rape that she too had been raped, in 1978.[2] Her blog, A Don's Life, gets about 40,000 hits a day, according to The Independent (2013).[67]

In August 2014, Beard was one of 200 public figures who were signatories to a letter to The Guardian expressing their hope that Scotland would vote to remain part of the United Kingdom in September's referendum on that issue.[68] In July 2015, Beard endorsed Jeremy Corbyn's campaign in the Labour Party leadership election. She said: "If I were a member of the Labour Party, I would vote for Corbyn. He actually seems to have some ideological commitment, which could get the Labour Party to think about what it actually stands for."[69]

Books

- Rome in the Late Republic (with Michael Crawford, 1985, revised 1999); ISBN 0-7156-2928-X

- The Good Working Mother's Guide (1989); ISBN 0-7156-2278-1

- Pagan Priests: Religion and Power in the Ancient World (as editor with John North, 1990); ISBN 0-7156-2206-4

- Classics: A Very Short Introduction (with John Henderson, 1995); ISBN 0-19-285313-9

- Religions of Rome (with John North and Simon Price, 1998); ISBN 0-521-30401-6 (vol. 1), ISBN 0-521-45015-2 (vol. 2)

- The Invention of Jane Harrison (Harvard University Press, 2000); ISBN 0-674-00212-1 (About Jane Ellen Harrison, 1850-1928, one of the first female career academics)

- Classical Art from Greece to Rome (with John Henderson, 2001); ISBN 0-19-284237-4

- The Parthenon (Harvard University Press, 2002); ISBN 1-86197-292-X

- The Colosseum (with Keith Hopkins, Harvard University Press, 2005); ISBN 1-86197-407-8

- The Roman Triumph (Harvard University Press, 2007); ISBN 0-674-02613-6

- Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town (2008); ISBN 1-86197-516-3 (US title: The Fires of Vesuvius: Pompeii Lost and Found; Harvard University Press)

- It's a Don's Life (Profile Books, 2009); ISBN 978-1846682513

- All in a Don's Day (Profile Books, 2012); ISBN 978-1846685361

- Confronting the Classics: Traditions, Adventures and Innovations (Profile Books, 2013); ISBN 1-78125-048-0

- Laughter in Ancient Rome: On Joking, Tickling, and Cracking Up (University of California Press, 2014); ISBN 0-520-27716-3

- SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome (Profile Books, 2015); ISBN 9780871404237

- Women & Power: A Manifesto (Profile Books, 2017); ISBN 978-1788160605

- Civilisations: How Do We Look / The Eye of Faith (Profile Books, 2018); ISBN 978-1781259993

See also

References

- ↑ "Prof. Mary Beard profile". Debrett's People of Today. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 Mead, Rebecca (25 August 2014). "The Troll Slayer". The New Yorker. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- 1 2 "Appointments, reappointments, and grants of title". Cambridge University Reporter. CXXXV.20 (5992). 2 March 2005.

- ↑ "A Don's Life". The Times Literary Supplement. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ↑ "Mary Beard: A Don's Life Archives – TheTLS". TheTLS. Retrieved 2018-02-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Laity, Paul (10 November 2007). "The dangerous don". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- 1 2 "No. 62310". The London Gazette (Supplement). 9 June 2018. p. B7.

- 1 2 3 4 McCrum, Robert (24 August 2008). "Up Pompeii with the roguish don". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "BEARD, Prof (Winifred) Mary". Debrett's People of Today. 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2008. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Laity, Interview by Paul (10 November 2007). "A life in writing: Mary Beard, Britain's best-known classicist". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ↑ McCrum, Robert (23 August 2008). "Interview with Mary Beard, the classical world's most provocative figure". The Observer. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ↑ "James Klugmann, a complex communist". openDemocracy. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ↑ Patterson, Christina (15 March 2015). "Mary Beard interview: 'I hadn't realised that there were people like that'". The Independent. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ Chhibber, Ashley (3 May 2013). "Interview: Mary Beard". The Cambridge Student. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "The book that made me a feminist". The Guardian. 2017-12-16. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2018-01-06.

- ↑ "The Cambridge MA". University of Cambridge. 26 January 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ↑ Collins, Nick (12 February 2011). "Oxbridge students' MA 'degrees' under threat". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK.

- ↑ Beard, Mary; Crawford, Michael (1985). Rome in the Late Republic:Problems and Interpretations. London: Gerald Duckworth.

- ↑ Beard, Mary (16 August 2017). "Remembering John Sturrock – TheTLS". TheTLS. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ↑ McCrum, Robert (23 August 2008). "Interview with Mary Beard, the classical world's most provocative figure". The Observer. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ↑ "Weird Thoughts (1994)". The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Film and Television. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ↑ Beard, Mary (4 October 2001). "11 September attacks". London Review of Books. 23 (19): 20–25. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ↑ "The Sather Professor". University of California, Berkeley Department of Classics. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ↑ "Sigmund H. Danziger Jr. Memorial Lecture Series". University of Chicago. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ↑ Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town. London, UK: Profile. 2008. ISBN 1-86197-516-3. (U.S. title: The Fires of Vesuvius: Pompeii Lost and Found, Harvard University Press)

- ↑ "A Point of View, On Age and Beauty". BBC Radio 4. 13 November 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ "A Point of View, The Oxbridge Interview". BBC Radio 4. 27 November 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- 1 2 John-Paul Ford Rojas "Mary Beard hits back at AA Gill after he brands her 'too ugly for television'", Daily Telegraph;, 24 April 2012

- ↑ "Mary Beard: AA Gill's attack on my looks felt like a punch". Telegraph. 24 September 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- 1 2 Williams, Zoe (23 April 2016). "Mary Beard: 'The role of the academic is to make everything less simple'". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ O’Donovan, Gerard (26 July 2013). "Mary Beard takes on Caligula, the emperor with the worst reputation in history". Telegraph. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ Thorpe, Vanessa (28 April 2012). "Mary Beard: the classicist with the common touch | Observer profile". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ Patterson, Christina (15 March 2013). "Mary Beard interview: 'I hadn't realised that there were people like". The Independent. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ Dowell, Ben (21 January 2013). "Mary Beard suffers 'truly vile' online abuse after Question Time". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ↑ "Cambridge professor under fire for Boston immigration comments on BBC Question Time". Boston Standard. 21 January 2013.

- ↑ Beard, Mary (27 January 2013). "Internet fury: or having your anatomy dissected online". The Times Literary Supplement. Archived from the original on 7 August 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ↑ Turner, Lark (15 February 2013). "In Britain, an Authority on the Past Stares Down a Nasty Modern Storm". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

I've chosen to be this way because that's how I feel comfortable with myself," Beard said. "That's how I am. It's about joining up the dots between how you look and how you feel inside, and I think that's what I've done, and I think people do it differently.

- ↑ "Bomb threat tweet sent to classicist Mary Beard". BBC News. 4 August 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ O’Donovan, Gerard (26 July 2013). "Mary Beard takes on Caligula, the emperor with the worst reputation in history". Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ "Mary Beard: 'I will never have a makeover'". Telegraph. 26 July 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ Wood, Gaby (16 March 2014). "Oh Do Shut Up Dear!, BBC Four, review". Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ Beard, Mary (3 March 2017). "Video: Women in Power". London Review of Books.

- ↑ "Mary Beard: We are living in an age when men are proud to be ignorant". Evening Standard. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ "Question Time". BBC One. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ Demianyk, Graeme (10 December 2015). "BBC Question Time: Cambridge Scholar Mary Beard Thinks Jeremy Corbyn Has Acted With 'Dignity' Against Hostile Media". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ "Pompeii: New Secrets Revealed with Mary Beard". BBC One. 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ↑ "Mary Beard's Ultimate Rome: Empire Without Limit". BBC Two. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "Julius Caesar Revealed". BBC One. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ "Civilisations". BBC Two. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ Ando, Clifford (29 February 2016). "The Rise and Rise of Rome". The New Rambler. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ↑ "List of Fellows (B)". Society of Antiquaries of London. Archived from the original on 24 June 2012.

- ↑ Thorpe, Vanessa (29 April 2012). "Mary Beard: the classicist with the common touch". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Professor Mary Beard". British Academy. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ↑ "No. 60367". The London Gazette (Supplement). 29 December 2012. p. 9.

- ↑ Reach, Kirsten (14 January 2014). "NBCC finalists announced". Melville House Publishing. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "Announcing the National Book Critics Awards Finalists for Publishing Year 2013". National Book Critics Circle. 14 January 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "Mary Beard joins list of famous names including Stephen Hawking and Hilary Mantel to receive Bodleian Libraries medal". Oxford Mail. 22 February 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ "List of Laureates: Mary Beard". Princess of Asturias Awards. Fundación Princesa de Asturias. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "Mary Beard : UC3M". UC3M. September 4, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

Mary Beard [...] will be invested as Honorary Doctor of Universidad Carlos III de Madrid (UC3M) for her important academic and professional merits...

- ↑ Clark, Nick (10 April 2013). "Mary Beard named as Royal Academy of Arts professor of ancient literature". The Independent.

- ↑ Bannerman, Lucy (2018-02-19). "Oxfam sex scandal: Mary Beard attacked for 'colonial' tweet". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- 1 2 Ramaswamy, Chitra (2018-02-19). "The fallout from Mary Beard's Oxfam tweet shines a light on genteel racism | Chitra Ramaswamy". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- 1 2 "Mary Beard posts tearful picture of herself after defence of Oxfam aid workers provokes backlash". The Independent. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- 1 2 "Mary Beard and white feminism's crocodile tears | gal-dem". gal-dem. 2018-02-23. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- ↑ Gopal, Priyamvada (2018-02-18). "Response to Mary Beard". Priyamvada Gopal. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- ↑ "Mary Beard posts picture of her crying following backlash over defence of Oxfam aid workers". PinkNews. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- ↑ "Mary Beard interview: 'I hadn't realised that there were people like". Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ↑ "Celebrities' open letter to Scotland – full text and list of signatories". The Guardian. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Michael (27 July 2015). "Mary Beard joins Jeremy Corbyn's celebrity backers in Labour leadership race". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

External links

- Mary Beard profile, classics.cam.ac.uk

- Mary Beard's blog, A Don's Life

- Beard, Mary (8 September 2000). "The story of my rape". The Guardian.

- Beard, Mary (14 February 2014). "The Public Voice of Women". London Review of Books.

- Debretts People of Today