Marion Mahony Griffin

| Marion Mahony Griffin | |

|---|---|

2.jpg) Mahony Griffin in Sydney, 1930 | |

| Born |

Marion Mahony 14 February 1871 Chicago, Illinois |

| Died |

August 10, 1961 (aged 90) Chicago, Illinois |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| Occupation | Architect; artist |

| Years active | 1890s–1950s |

| Known for | Prairie School |

| Spouse(s) | Walter Burley Griffin (m. 1911) |

Marion Mahony Griffin (February 14, 1871 – August 10, 1961) was an American architect and artist. She was one of the first licensed female architects in the world, and is considered an original member of the Prairie School.[1] Her work in the United States developed and expanded the American Prairie School. Her work in India and Australia reflected Prairie School ideals of indigenous landscape and materials in the newly formed democracies. The scholar Deborah Wood has stated that Griffin "did the drawings people think when they think Frank Lloyd Wright (one of her collaborating architects)."[2] During her career, she produced some of the best architectural drawing in America and was instrumental in envisioning the design plans for then new capital city of Australia, Canberra.[3][4]

Early life and education

Marion Mahony was born in 1871 in Chicago, Illinois, the second child and eldest daughter of the five surviving children of Jeremiah Mahony, a journalist, poet, and educator[5] from Cork, Ireland, and Clara Hamilton, a schoolteacher. Comically, Marion's father "had the reputation of being a better teacher drunk than most teachers sober" while her mother can only be noted as being the daughter of a respected doctor from New Hampshire.[6]

Marion's family moved to nearby Winnetka in 1880 after the Great Chicago fire. In her memoir Mahoney vividly describes her mother carrying her as an infant in a clothes basket, as they escape from the raging fire. Growing up in Winnetka, she became fascinated by the quickly disappearing landscape as suburban homes filled the area. She was influenced by her first cousin, architect Dwight Perkins, and decided to further her education. She graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T.) in 1894. She was the second woman to do so, after Sophia Hayden, the designer of the Woman's building at the 1893 Chicago World's Columbian Exposition.[7] Though highly talented, she sometimes struggled with her place in both society and the field. She was unsure of her ability to complete the thesis required for her bachelor's degree, but her professor, Constant-Désiré Despradelle, pushed her forward.[8]

Architectural career

Work with Frank Lloyd Wright

After graduation, Mahony returned to Chicago, where she became the first woman to be licensed to practice architecture in Illinois. She worked in her cousin's architecture firm, which was located in Steinway Hall at 64 E. Van Buren in downtown Chicago. The space was shared with many other architects, including Robert C. Spencer, Myron Hunt, Webster Tomlinson, Irving Pond and Allen Bartlitt Pond, Adamo Boari, Birch Long and Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1895, Mahony, the first employee hired by Frank Lloyd Wright, went to work designing buildings, furniture, stained glass windows and decorative panels.[9] Her beautiful watercolor renderings of buildings and landscapes became known as a staple of Wright's style, though she was never given credit by the famous architect. Over a century later she would be known as one of the greatest delineators of the architecture field, but during her life her talent was seen as only an extension of the work done by male architects. She would be associated with Wright's studio for almost fifteen years and was an important contributor to his reputation, particularly for the influential Wasmuth Portfolio, for which Mahony created more than half of the numerous renderings. Architectural writer Reyner Banham called her the "greatest architectural delineator of her generation". Her rendering of the K. C. DeRhodes House in South Bend, Indiana, was praised by Wright upon its completion and by many critics.[10]

Wright understated the contributions of others of the Prairie School, Mahony included. A clear understanding of Marion Mahony's contribution to the architecture of the Oak Park Studio comes from Wright's son, John Lloyd Wright, who says that William Drummond, Francis Barry Byrne, Walter Burley Griffin, Albert Chase McArthur, Marion Mahony, Isabel Roberts and George Willis were the draftsmen—the five men and two women who each made valuable contributions to Prairie style architecture for which Wright became famous.[11] During this time Mahony designed the Gerald Mahony Residence (1907) in Elkhart, Indiana for her brother and sister-in-law.[12]

When Wright eloped to Europe with Mamah Borthwick Cheney in 1909, he offered the Studio's work to Mahony. She declined. But after Wright had gone, Hermann V. von Holst, who had taken on Wright's commissions, hired Mahony with the stipulation that she would have control of design.[13] In this capacity, Mahony was the architect for a number of commissions Wright had abandoned. Two examples were the first (unbuilt) design for Henry Ford's Dearborn mansion, Fair Lane and the Amberg House in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Work with Walter Burley Griffin

Mahony recommended Walter Burley Griffin to von Holst to develop landscaping for the area surrounding the three houses commissioned from Wright in Decatur, Illinois. Griffin was a fellow architect, a fellow ex-employee of Wright, and a leading member of the Prairie School of architecture. Mahony and Griffin worked on the Decatur project before their marriage; afterwards, Mahony worked in Griffin's practice. A Walter Burley Griffin/Marion Mahony designed development that is home to an outstanding collection of Prairie School dwellings, Rock Crest – Rock Glen in Mason City, Iowa, is seen as their most dramatic American design development of the decade. It is the largest collection of Prairie Style homes surrounding a natural setting.

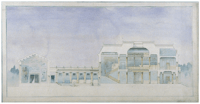

Mahony and Griffin married in 1911, a partnership that lasted 28 years. Marion's watercolor perspectives of Walter's design for Canberra, the new Australian capital, were instrumental in securing first prize in the international competition for the plan of the city. In 1914 the couple moved to Australia to oversee the building of Canberra. Marion managed the Sydney office and was responsible for the design of their private commissions.[14] In Australia, Marion and Walter were introduced to Anthroposophy and the ideas of Rudolf Steiner which they embraced enthusiastically, and in Sydney they joined the Anthroposophy Society.[4] In Australia, they pioneered the Knitlock construction method, inexactly emulated by Wright in his California textile block houses of the 1920s.

Later the Griffins practiced in India and, in less than a year, Mahony oversaw the design of over one hundred Prairie School influenced buildings there.[15] Walter Griffin died in India in 1937 of peritonitis following a cholecystectomy. Mahony then completed their work and returned to Australia. Mahony and Griffin spread the Prairie Style to two continents, far from its origins. She credited Louis Sullivan as the impetus for the Prairie School philosophy. She thought Wright's habit of taking credit for the movement explained its early death, in the United States.[16]

Death and legacy

Marion Mahony Griffin died in Chicago, aged 90. She was in her late 60's when she returned to the United States and afterward was largely retired from her architectural career. "The one time she addressed the Illinois Society of Architects, she made no mention of her work, instead lectured the crowd on anthroposophy, a philosophy of spiritual knowledge developed by Rudolf Steiner."[17]

She is buried in Graceland Cemetery, Irving Park Road and Clark Street, Chicago, with other noted architects: David Adler, Louis Sullivan, Daniel H. Burnham, Bruce Goff, William Holabird, Howard Van Doren Shaw and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

In 2015, the beach at Jarvis Avenue in Rogers Park, Chicago was named in Mahony Griffin's honor. When she returned to the United States in 1939, after her husband's death, she lived near the beach. The Australian Counsel General, Roger Price, attended the beach's dedication for the woman who was instrumental in the design the Australian capital.[18]

An exhibition of some of her work was held at the Block Museum of Northwestern University in 2015. In 2016-17, an exhibit of her work is on display at the Elmhurst History Museum.[19]

In the United States there are a few surviving works attributed to Mahoney. There is a small mural in George B. Armstrong elementary school in Chicago attributed to Mahoney, and several homes in Decatur.

Architectural works

- All Souls Church (demolished), Evanston, Illinois – 1901

- The Gerald and Hattie Mahony Residence (demolished), Elkhart, Indiana - 1907[20]

- David Amberg Residence, 505 College Avenue SE, Grand Rapids, Michigan - 1909[21]

- Edward P. Irving Residence, 2 Millikin Place, Decatur, Illinois - 1909[22]

- Robert Mueller Residence, 1 Millikin Place, Decatur, Illinois - 1909[23]

- Adolph Mueller Residence, 4 Millikin Place, Decatur, Illinois - 1910[24][25]

- Niles Club Company, Club House, Niles, Michigan - 1911[26]

- Henry Ford Residence "FairLane" (unbuilt initial design; 1913)

- Koehne House (demolished 1974), Palm Beach, Florida - 1914[27][28][29][30]

- Cooley Residence, Grand St. at Texas Avenue, Monroe, Louisiana[31]

- Fern Room, Cafe Australia, Melbourne, Australia - 1916

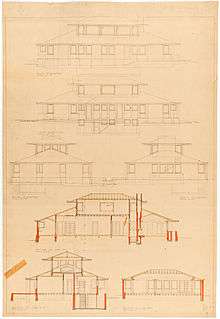

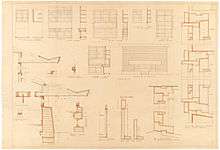

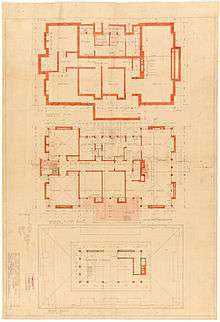

Design for a Suburban Residence Exhibit Plan 3

Design for a Suburban Residence Exhibit Plan 3 - Capitol Theatre, Swanston Street, Melbourne, Australia – 1921-23[32]

- "Stokesay", residence of Mr. & Mrs. Onians, 289 Nepean Highway, Seaford, Victoria, Australia - 1925

- Ellen Mower Residence, 12 The Rampart, Castlecrag, Sydney - 1926

- Creswick Residence, Castlecrag, Sydney, Australia - 1926

- S.R. Salter Residence (Knitlock construction), Toorak, Victoria, Australia - 1927[33]

- Vaughan Griffin Residence, 52 Darebin St., Heidelberg, Victoria, Australia - 1927[34]

References

- ↑ The First American Women Architects, by Sarah Allaback, p. 87

- ↑ Bernstein, Fred A. (2008). "Marion Mahony Griffin - Architecture". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- ↑ Korporaal, Glenda (16 October 2015). "Making Magic - The Marion Mahony Griffin story". canberratimes.com.au. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- 1 2 Paull, John (2012) Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin, Architects of Anthroposophy, Journal of Bio-Dynamics Tasmania, 106 (Winter), pp. 20-30.

- ↑ Anna Rubbo, "Marion Mahony Griffin: A Portrait," in Walter Burley Griffin—A Re-View, ed. Jenepher Duncan (Clayton, Victoria, Australia: Monash University Gallery, 1988), 16; James Weirick, "Marion Mahony at M.I.T.," Transition 25, no. 4 (1988): 49.

- ↑ Griffin, MOA, VI, 92.

- ↑ Hines, Thomas S. (March 1995). "Portrait: Marion Mahony Griffin Drafting a Role for Women in Architecture". Architectural Digest. 52 (1): 28–40.

- ↑ The American Midwest, by Richard Sisson, Christian K. Zacher, Andrew Robert Lee Cayton, Indiana University Press, 2007, p. 558

- ↑ Walter Burley Griffin, by Paul Kruty, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- ↑ Frank Lloyd Wright's Right-Hand Woman, by Lynn Becker, 2005

- ↑ "My Father: Frank Lloyd Wright", by John Lloyd Wright; 1992; p. 35

- ↑ "Interior view of Gerard Mahony House [picture]". nla.gov.au. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ Mahony Griffin, Marion, "The Magic of America"

- ↑ "Marion Mahony". prairiestyles.com. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ The First American Women Architects, by Sarah Allaback, p. 89

- ↑ The Magic of America: Electronic Edition online version of Marion Mahony Griffin's unpublished manuscript, made available through The Art Institute of Chicago

- ↑ Bernstein, Fred. "Rediscovering a Heroine of Chicago Architecture". ny times. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- ↑ Woodard, Ben (May 22, 2015). "Aussie Beach". Edgewater News. A2. DNAinfo.com.

- ↑ Tribune, Chicago. "Elmhurst exhibit on female architectural pioneer highlights out-of-box ideas". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "Exterior view of Gerald Mahony House [picture]". nla.gov.au. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ Heritage Hills Tours website

- ↑ Prairie School Traveler.com website

- ↑ "The Prairie School Traveler". prairieschooltraveler.com. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "Architecture - Adolph Mueller House". pbs.org. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "The Prairie School Traveler". prairieschooltraveler.com. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "No title available". nla.gov.au. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "Interior view of Koehne House,Florida, U.S.A. [United States of America, 1] [picture]". nla.gov.au. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "Interior view of Koehne House,Florida, U.S.A. [United States of America, 2] [picture]". nla.gov.au. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "Exterior view of Koehne House, Florida, U.S.A. [United States of America, 1] [picture]". nla.gov.au. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "Exterior view of Cooley residence, Monroe, Louisiana, U.S.A.[United States of America, 2] [picture]". nla.gov.au. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "Exterior view of Cooley residence, Monroe, Louisiana, U.S.A.[United States of America,1] [picture]". nla.gov.au. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ Beyond Architecture, (editors) Marion Mahony Griffin, Anne Watson, Walter Burley Griffin

- ↑ "[Mr. S.R. Salter's completed Knitlock home at Toorak, Victoria, 1] [picture]". nla.gov.au. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "Mr. Vaughan Griffin's segmental house at 52 Darebin Street, Heidelberg, Victoria, ca. 1927, [1] [picture]". nla.gov.au. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

Sources

- Birmingham, Elizabeth. "The Case of Marion Mahony Griffin and The Gendered Nature of Discourse in Architectural History." Women's Studies 35, no. 2 (March 2006): 87-123.

- Brooks, H. Allen, Frank Lloyd Wright and the Prairie School, Braziller (in association with the Cooper-Hewitt Museum), New York 1984; ISBN 0-8076-1084-4

- Brooks, H. Allen, The Prairie School, W.W. Norton, New York 2006; ISBN 0-393-73191-X

- Brooks, H. Allen (editor), Prairie School Architecture: Studies from "The Western Architect", University of Toronto Press, Toronto & Buffalo 1975; ISBN 0-8020-2138-7

- Brooks, H. Allen, The Prairie School: Frank Lloyd Wright and his Midwest Contemporaries, University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1972; ISBN 0-8020-5251-7

- Hasbrouk, Wilbert R. 2012. "Influences on Frank Lloyd Wright, Blanche Ostertag and Marion Mahony." Journal of Illinois History 15, no. 2: 70-88. America: History & Life.

- Kruty, Paul. "Griffin, Marion Lucy Mahony", American National Biography Online, February 2000.

- Van Zanten, David (editor) Marion Mahony Reconsidered, University of Chicago Press, 2011; ISBN 9780226850818

- Waldheim, Charles, Katerina Rüedi, Katerina Ruedi Ray; Chicago Architecture: Histories, Revisions, Alternatives, University of Chicago Press, 2005; ISBN 0-226-87038-3, ISBN 978-0-226-87038-0

- Wood, Debora (editor), Marion Mahony Griffin: Drawing the Form of Nature, Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art and Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Illinois 2005; ISBN 0-8101-2357-6

External links

- "Exhibit honors unsung architect Marion Mahony Griffin", Chicago Tribune, October 11, 2016

- Marion Mahony Griffin, Digital Projects, New-York Historical Society

- Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin architectural drawings, circa 1909-1937.Held by the Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

- Biographical notes at MIT

- Marion Mahony Griffin: Drawing the Form of Nature an exhibition of Mahony Griffin's graphic art at the Block Museum, Northwestern University, United States of America

- The Magic of America: Electronic Edition online version of Marion Mahony Griffin's unpublished manuscript, made available through the Art Institute of Chicago

- "Rediscovering a Heroine of Chicago Architecture", New York Times, January 1, 2008

- Bronwyn Hanna (2008). "Griffin, Marion Mahony". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Retrieved 9 October 2015. [CC-By-SA]

- Marion Mahony Griffin at Find a Grave

- National Archives of Australia

- Pioneering Women of American Architecture

- Willoughby City Council Heritage

- Places Journal, Marion Mahoney Griffin

- National Library of Australia: Griffin and Early Canberra Collection

- ↑ Hines, Thomas (March 1995). "Drafting a Role for Women in Architecture". Architectural Digest. 52 (1): 28–40.