Maputo Protocol

| Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa | |

|---|---|

| Type | Human rights instrument (women) |

| Drafted | March 1995 (Lome, Togo)[1] |

| Signed | 11 July 2003 |

| Location | Maputo, Mozambique |

| Effective | 25 November 2005 |

| Condition | Ratification by 15 nations of the African Union |

| Signatories | 49 |

| Parties | 37 |

| Depositary | African Union Commission |

| Languages | English, French |

The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, better known as the Maputo Protocol, guarantees comprehensive rights to women including the right to take part in the political process, to social and political equality with men, improved autonomy in their reproductive health decisions, and an end to female genital mutilation.[2] As the name suggests, it was adopted by the African Union in the form of a protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights in Maputo, Mozambique.

Origins

Following on from recognition that women's rights were often marginalised in the context of human rights, a meeting organised by Women in Law and Development in Africa (WiLDAF) in March 1995, in Lomé, Togo called for the development of a specific protocol to the African Charter on Human and People's Rights to address the rights of women. The OAU assembly mandated the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights (ACHPR) to develop such a protocol at its 31st Ordinary Session in June 1995, in Addis Ababa.[3]

A first draft produced by an expert group of members of the ACHPR, representatives of African NGOs and international observers, organised by the ACHPR in collaboration with the International Commission of Jurists, was submitted to the ACHPR at its 22nd Session in October 1997, and circulated for comments to other NGOs.[3] Revision in co-operation with involved NGO's took place at different sessions from October to January, and in April 1998, the 23rd session of the ACHPR endorsed the appointment of Julienne Ondziel Gnelenga, a Congolese lawyer, as the first Special Rapporteur on Women's Rights in Africa, mandating her to work towards the adoption of the draft protocol on women's rights.[3] The OAU Secretariat received the completed draft in 1999, and in 2000 at Addis Ababa it was merged with the Draft Convention on Traditional Practices in a joint session of the Inter African Committee and the ACHPR.[3] After further work at experts meetings and conferences during 2001, the process stalled and the protocol was not presented at the inaugural summit of the AU in 2002.

In early 2003, Equality Now hosted a conference of women's groups, to organise a campaign to lobby the African Union to adopt the protocol, and the protocol's text was brought up to international standards. The lobbying was successful, the African Union resumed the process and the finished document was officially adopted by the section summit of the African Union, on 11 July 2003.[3]

Adoption and ratification

The protocol was adopted by the African Union on 11 July 2003 at its second summit in Maputo, Mozambique.[4] On 25 November 2005, having been ratified by the required 15 member nations of the African Union, the protocol entered into force.[5]

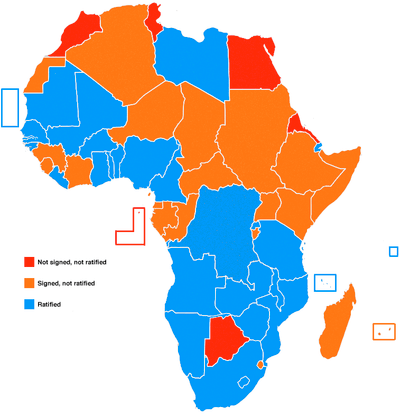

Of the 54 member countries in the African Union, 49 have signed the protocol and 37 have ratified and deposited the protocol.[6] The AU states that have neither signed nor ratified the Protocol are Botswana and Egypt. The states that have signed but not ratified are Algeria, Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Mauritius, Niger, São Tomé and Príncipe, Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Tunisia.

Reservations

At the Maputo Summit, several countries expressed reservations.[1]

Tunisia, Sudan, Kenya, Namibia and South Africa recorded reservations about some of the marriage clauses. Egypt, Libya, Sudan, South Africa and Zambia had reservations about "judicial separation, divorce and annulment of marriage." Burundi, Senegal, Sudan, Rwanda and Libya held reservations with Article 14, relating to the "right to health and control of reproduction." Libya expressed reservations about a point relating to conflicts.

Articles

The main articles are:

- Article 2: Elimination of Discrimination Against Women

- Article 3: Right to Dignity

- Article 4: The Rights to Life, Integrity and Security of the Person

- Article 5: Elimination of Harmful Practices

- This refers to female genital mutilation and other traditional practices that are harmful to women.

- Article 6: Marriage

- Article 7: Separation, Divorce and Annulment of Marriage

- Article 8: Access to Justice and Equal Protection before the Law

- Article 9: Right to Participation in the Political and Decision-Making Process

- Article 10: Right to Peace

- Article 11: Protection of Women in Armed Conflicts

- Article 12: Right to Education and Training

- Article 13: Economic and Social Welfare Rights

- Article 14: Health and Reproductive Rights

- Article 15: Right to Food Security

- Article 16: Right to Adequate Housing

- Article 17: Right to Positive Cultural Context

- Article 18: Right to a Healthy and Sustainable Environment

- Article 19: Right to Sustainable Development

- Article 20: Widows' Rights

- Article 21: Right to Inheritance

- Article 22: Special Protection of Elderly Women

- Article 23: Special Protection of Women with Disabilities

- Article 24: Special Protection of Women in Distress

- Article 25: Remedies

Opposition

There are two particularly contentious factors driving opposition to the Protocol: its article on reproductive health, which is opposed mainly by Catholics and other Christians, and its articles on female genital mutilation, polygamous marriage and other traditional practices, which are opposed mainly by Muslims.

Christian opposition

Pope Benedict XVI has described the Protocol as "an attempt to trivialize abortion surreptitiously".[7] The Roman Catholic bishops of Africa oppose the Maputo Protocol because it defines abortion as a human right. The US-based pro-life advocacy organisation, Human Life International, describes it as "a Trojan horse for a radical agenda."[8]

In Uganda, the powerful Joint Christian Council opposed efforts to ratify the treaty on the grounds that Article 14, in guaranteeing abortion "in cases of sexual assault, rape, incest, and where the continued pregnancy endangers the mental and physical health of the mother or the life of the mother or the foetus," is incompatible with traditional Christian morality.[9] In an open letter to the government and people of Uganda in January 2006, the Catholic Bishops' Conference of Uganda set out their opposition to the ratification of the Maputo Protocol.[10] It was nevertheless ratified on 22 July 2010.[11]

Muslim opposition

In Niger, the Parliament voted 42 to 31, with 4 abstentions, against ratifying it in June 2006; in this Muslim country, several traditions banned or deprecated by the Protocol are common.[12] Nigerien Muslim women's groups in 2009 gathered in Niamey to protest what they called "the satanic Maputo protocols", specifying limits to marriage age of girls and abortion as objectionable.[13]

In Djibouti, however, the Protocol was ratified in February 2005 after a subregional conference on female genital mutilation called by the Djibouti government and No Peace Without Justice, at which the Djibouti Declaration on female genital mutilation was adopted. The document declares that the Koran does not support female genital mutilation, and on the contrary practising genital mutilation on women goes against the precepts of Islam.[14][15][16]

See also

References

- 1 2 AU Executive Council endorses protocol on women's rights, Panafrican News Agency (PANA) Daily Newswire, 7 September 2003

- ↑ The Maputo Protocol of the African Union, brochure produced by GTZ for the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rights of Women in Africa: Launch of a Petition to the African Union Archived 12 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine., Mary Wandia, Pambazuka News 162; 24 June 2004, republished in "African Voices on Development and Social Justice Editorial from Pambazuka News 2004" by Firoze Manji (Ed.) and Patrick Burnett (Ed.), Mkuki na Nyota Publishers, Tanzania, ISBN 978-9987-417-35-3

- ↑ African Union: Rights of Women Protocol Adopted, press release, Amnesty International, 22 July 2003

- ↑ UNICEF: toward ending female genital mutilation, press release, UNICEF, 7 February 2006

- ↑ List of countries which have Signed, Ratified/Acceded the Maputo Protocol Archived 14 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine., African Union official website

- ↑ Pope to diplomats: Respect for rights, desires is only path to peace, 8 January 2007, Catholic News Service

- ↑ Marking The International Day of Women, 8 March 2008, Vatican Radio

- ↑ Rights Treaty in Uganda Snags on 'African Values', Women's eNews, 2 June 2008

- ↑ Open Letter to the Government and People of Uganda Concerning the Ratification of the Protocol to the African Charter on Human Rights and Peoples' Right: On the Rights of Women in Africa, Catholic Bishops' Conference of Uganda, document hosted at Eternal Word Television Network

- ↑ http://www.africa4womensrights.org/post/2010/08/02/Uganda-becomes-the-28th-State-Party-to-the-Maputo-Protocol!

- ↑ Niger MPs reject protocol on women's rights, Independent Online, 6 June 2006

- ↑ JOURNÉE NATIONALE DE LA FEMME NIGÉRIENNE: Les femmes musulmanes s’opposent aux ‘’textes sataniques’’ relatifs à la femme. Mamane Abdou, Roue de l’Histoire (Niamey) n° 456. 14 May 2009.

- ↑ Djibouti ratifies the Maputo Protocol against the practice. Conference in Djibouti affirms Koran says nothing about it, WADI

- ↑ DJIBOUTI: Anti-FGM protocol ratified but huge challenges remain, 14 December 2008, IRIN

- ↑ Second Thematic Session Third Report – Le Protocole de Maputo, French, recording announcement of the Djibouti government's imminent intention to ratify the Maputo Protocol, No Peace Without Justice, 2 February 2005

External links

- Treaties and protocols of the African Union – African Union official website

- The Maputo Protocol in the news, stopfgmc.org, the website of the International Campaign for the Abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation

- Page on the protocol at the official ACHPR website.

- Maputo Protocol text at Archive.is (archived 2012-12-04) Will men and women ever be equal?This is a vexed issue.Kenya has signed regional instruments and international instruments on elimination of discrimination against women but in terms of implementation it remains so near yet so far.The Kenya judicial system has also been faced.In the case of Mary Wanjuhi Muigai v Attorney General & another [2015] eKLR,Justice Mumbi Ngugi wondered that “Can men and women ever be equal, within the meaning contemplated in the Constitution, within a polygamous marriage" In my view, to talk of equality of men and women within a polygamous situation is a bit of an oxy-moronic phrase, if one may coin the term. Equality would presuppose that a woman has the same right as the man to take on a second spouse during the subsistence of the marriage, the practice defined as polyandry. This is not recognized in any of the cultures of the people of Kenya, so it must be accepted that polygamy precludes equality between men and women. Polygamy cannot therefore be said to promote equality between men and women, and if measured against the clear provisions of the Constitution and international conventions to which Kenya is a party, is clearly unconstitutional and a form of discrimination against women. However, it is a practice that has been accepted in Kenyan society. Registration of polygamous marriages appears to have been accepted, even by women, as the lesser evil, and has been recommended in various reports, including the 1968 Report of the Commission on the Law of Marriage and Divorce in Kenya. While this Court accepts that permitting polygamous marriages without the consent of a previous wife or wives is not consistent with the Constitution, and that indeed the practice of polygamy is in itself not consistent with the equality principles in the Constitution, it also recognizes that there are situations and practices that it cannot regulate, and that must be left to the wishes and dictates of the people, through their duly elected representatives, as well as to the individual choices of those adults contracting marriages, and who willingly enter into polygamous or potentially polygamous marriages. It is noteworthy that in many cultures in Kenya, polygamy was accepted. It was not, however, subject to registration, and in the event of the demise of a husband, as a perusal of many decisions in the Family Division will reveal, the Court was often required to hear evidence to establish whether the women who claimed to be wives of the deceased were indeed wives and entitled to inheritance from his estate. This, in my view, was the reason why the registration of customary marriages was necessary-to bring some degree of certainty to a system of marriage practiced by many, yet was outside the reach of the law.That the practice of polygamy and registration of polygamous marriages without the consent of the previous wife or wives is inconsistent with the equality provisions of the Constitution.”

Justice Mumbi Ngugi also reiterated her contention that the Marriage Act has also failed to uphold the equality provisions in Article 45 by providing for polygamous marriages without the consent of the existing wives, and in her view, there is no equality in marriage in the Marriage Act. It is disheartening to date since the holding of the above decision no attempt has been made to amend the Marriage Act 2014 to align with Article 45 of the Constitution.