Man Bites Dog (film)

| Man Bites Dog | |

|---|---|

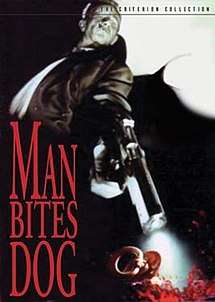

Criterion Collection DVD cover | |

| Directed by |

Rémy Belvaux André Bonzel Benoît Poelvoorde |

| Produced by |

Rémy Belvaux André Bonzel Benoît Poelvoorde |

| Screenplay by |

Rémy Belvaux André Bonzel Benoît Poelvoorde Vincent Tavier |

| Story by | Rémy Belvaux |

| Starring |

|

| Music by |

Jean-Marc Chenut Laurence Dufrene Philippe Malempré |

| Cinematography | André Bonzel |

| Edited by |

Rémy Belvaux Eric Dardill |

Production company |

Les Artistes Anonymes |

| Distributed by |

Acteurs Auteurs Associés (AAA) (France) Roxie Releasing (US) Metro Tartan Films (UK) |

Release date |

|

Running time |

95 minutes[1] 92 minutes[2] (Edited cut) |

| Country | Belgium |

| Language | French |

| Budget | BEF1 million (USD$33,000) |

| Box office | USD$205,569[3] |

Man Bites Dog (French: C'est arrivé près de chez vous, literally "It has Happened near your Home") is a 1992 Belgian black comedy crime mockumentary written, produced and directed by Rémy Belvaux, André Bonzel and Benoît Poelvoorde, who are also the film's co-editor, cinematographer and lead actor respectively.

The film follows a crew of filmmakers following a serial killer, recording his horrific crimes for a documentary they are producing. At first dispassionate observers, they find themselves caught up in the increasingly chaotic and nihilistic violence. The film received the André Cavens Award for Best Film by the Belgian Film Critics Association (UCC). Since its release, the picture has become a cult film, and received a rare NC-17 rating for its release in the U.S.[4][5]

Plot

Ben (Benoît Poelvoorde) is a witty, charismatic serial killer who holds forth at length about whatever comes to mind, be it the "craft" of murder, the failings of architecture, his own poetry, or classical music, which he plays with his girlfriend Valerie (Valérie Parent). A film crew joins him on his sadistic adventures, recording them for a fly on the wall documentary. Ben takes them to meet his family and friends while boasting of murdering many people at random and dumping their bodies in canals and quarries. The viewer witnesses these grisly killings in graphic detail.

Ben ventures into apartment buildings, explaining how it is more cost-effective to attack old people than young couples because the former have more cash at home and are easier to kill. In a following scene, he screams wildly at an elderly lady, causing her to have a heart attack. As she lies dying, he casually remarks that this method saved him a bullet. Ben continues his candid explanations and appalling rampage, shooting, strangling, and beating to death anyone who comes his way: women (he is misogynistic), immigrants (he is a racist xenophobe), and postmen (his favorite targets).

The camera crew becomes more and more involved in the murders, first as accomplices but eventually taking an active part in them. When Ben invades a home and kills an entire family, they help him hold down a young boy and smother him. They meet a competing camera crew and take turns shooting the three men. During filming, two of Ben's crew are killed; their deaths are later called "occupational hazards" by a crew member.

When Ben takes a couple hostage in their own home, he holds the man at gunpoint while he and the crew gang-rape the woman. The following morning, the camera dispassionately records the aftermath: the woman has been butchered with a knife, her entrails spilling out, and the man has been shot to death. Ben's violence becomes more and more random until he kills an acquaintance in front of his girlfriend and friends during a birthday dinner. Spattered with blood, they act as though nothing horrible has happened, continuing to offer Ben presents. The film crew disposes of the body for Ben.

After a victim flees before he can be killed, Ben is arrested, but he escapes. At this point someone starts taking revenge on him and his family. Ben discovers that his parents have been killed, along with his girlfriend Valerie: a flautist, she has been murdered in a particularly humiliating manner, with her flute inserted into her anus. This prompts Ben to decide that he must leave. He meets the camera crew to say farewell, but in the middle of reciting a poem he is abruptly shot dead by an off-camera gunman. The camera crew is then picked off one by one. After the camera falls, it keeps running, and the film ends with the death of the fleeing sound recordist.

Production

The film is shot in black and white and was produced on a shoe-string budget by four student filmmakers, led by director Rémy Belvaux. The film's writers, Belvaux, Poelvoorde and Bonzel, all appear in the film using their own first names: Poelvoorde as Ben, the killer; Belvaux as Rémy, the director; and Bonzel as André, the camera operator. The genesis of the idea came from shooting a documentary without any money. This film is rated NC-17 by the Motion Picture Association of America for "strong graphic violence".[6]

Although it is never shown or suggested in the film itself that Benoit kills a baby, the original poster features an image of a baby's pacifier with spattering blood coming from an unseen target at the end of Benoit's gun. For foreign release posters (not including the Region 4/Australian release), the baby's pacifier was changed to a set of dentures. In the R-rated version of the film that was made for the U.S. video audience (as NC-17 rated films were never allowed to be stocked at Blockbuster Video), the scenes where Ben and the crew work together to kill a young child are excised; the following scenes where Ben rapes a woman and the camera crew joins in are included but edited to have less nudity and gore.

Reception

Man Bites Dog received positive reviews upon release. Based on 18 reviews collected by Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an overall approval rating from critics of 72%, with an average score of 7.1/10.[7] LA Times film critic Kenneth Turan highly praises the film upon its release "Man Bites Dog defines audacity. An assured, seductive chamber of horrors, it marries nightmare with humor and then abruptly takes the laughter away. Intentionally disturbing, it is close to the last word about the nature of violence on film, a troubling, often funny vision of what the movies have done to our souls.... The deserving winner of the International Critics Award at Cannes ..."[8] Film critic Rob Gonsalves called the film "[an] original, a stark and (sorry) biting work far more complex, both stylistically and thematically, than first meets the eye." [9]

The film was screened at the 1992 Cannes Film Festival where it won the International Critics’ Prize,[10] the SACD award for Best Feature and the Special Award of the Youth for directors Rémy Belvaux, André Bonzel and Benoît Poelvoorde.[11] The film's controversial content and extreme violence was off-putting to some viewers, and resulted in the film being banned in Sweden.[11] In 2003, the video was banned in Ireland.[12]

References

- ↑ "MAN BITES DOG (18)". British Board of Film Classification. 1992-09-22. Retrieved 2013-01-16.

- ↑ "MAN BITES DOG (18)". British Board of Film Classification. 1993-07-02. Retrieved 2013-01-16.

- ↑ Man Bites Dog at Box Office Mojo

- ↑ "Man Bites Dog". 28 January 2010.

- ↑ "What's On Your Cult Film List?".

- ↑ "Man Bites Dog". 15 January 1993 – via IMDb.

- ↑ "Man Bites Dog".

- ↑ TURAN, KENNETH (2 April 1993). "MOVIE REVIEW : 'Man Bites Dog': Seductive Nature of Violence : The ragtag production allows us to cozy up to its charming killer, then, realizing his heinousness, gag on our self-satisfied black laughter" – via LA Times.

- ↑ Nieporent, Ben. "Movie Review - Man Bites Dog - eFilmCritic".

- ↑ "Man Bites Dog".

- 1 2 "The Quietus - Film - Film Features - 20 Years On: Man Bites Dog Revisited".

- ↑ "No.24 - 227-235 - 25032003" (PDF). Iris Oifigiúil. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

Bibliography

- Roscoe, Jane (2006): Man Bites Dog: Deconstructing the Documentary Look. In: Rhodes, Gary Don/Springer, John Parris (eds.) (2006): Docufictions. Essays on the intersection of documentary and fictional filmmaking. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, p. 205-215.