Malcolm Morley

Malcolm Morley (June 7, 1931 – June 1, 2018) was a British-American artist and painter. He was known as an artist who pioneered in varying styles, working as a photorealist and an expressionist, among many other styles.

Life

Morley was born in north London. He had a troubled childhood—after his home was partially blown up by a bomb during World War II, his family was homeless for a time[1]. He recalled that he had constructed a balsawood model of HMS Nelson and placed it on his windowsill when the German bomb destroyed the house along with the model. "The shock was so violent," writes one Morley expert, "that Morley repressed this memory until it resurfaced 30 years later during a psychoanalytic session."[2]

As a teenager, Morley was sentenced to three years at Wormwood Scrubs prison for housebreaking and petty theft. While there, he read Irving Stone's novel Lust for Life, based on the life of Vincent van Gogh, and enrolled in an art correspondence course.[2] He would later look back on these rough beginnings with some humor: "I [feel] very sorry for artists that haven’t had much happen in their early life," he once said.[3] Released after two years for good behavior, he joined an artists' colony in St. Ives, Cornwall, then studied art first at the Camberwell School of Arts, described by one art historian as being, at the time, "one of the more progressive and exciting art schools in London,"[4] and then at the Royal College of Art (1955–1957), where his fellow students included Peter Blake and Frank Auerbach[5]. In 1956, he saw the exhibition "Modern Art in the United States: A Selection from the Collections at the Museum of Modern Art"[2] at the Tate Gallery, and began to produce paintings in an abstract expressionist style. All the same, he would later say that "I would have liked to be Pollock, but I wouldn't want to be after Pollock. My ambition was too big."[4]

Morley visited New York, which was at the time a major center of the Western art world, in 1957. He moved there the following year, after which he met artists including Barnett Newman, Cy Twombly, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol[6]. His first solo exhibition was at Kornblee Gallery in 1964[7], partly at the urging of the art dealer Ivan Karp, who had a reputation as a talent spotter and had worked with the legendary dealer Leo Castelli.[8]

In the mid-1960s, Morley briefly taught at Ohio State University, and then moved back to New York City, where he taught at the School of Visual Arts (1967–69) and SUNY Stony Brook (1970–1974).[9]

Morley had early solo gallery exhibitions at venues including the Clocktower Gallery, Institute for Art and Urban Resources, New York (1976); Nancy Hoffman Gallery, New York (1979); and Stefanotty Gallery, New York (1979). He participated in the major international exhibition Documenta, in Kassel, in 1972[10] and 1977[11], and in the Carnegie International, in 1985.

The Whitechapel Gallery, in London, organized a major retrospective exhibition in 1983, resulting in his winning the inaugural Turner Prize, awarded by the Tate, in 1984[6]. The artist remembered the moment he learned he had won the prize: "When the call came to say he had won, he was sitting in his loft studio in the Bowery, 'watching a bum shitting on the street. It felt unreal: here I was watching this act; the next minute I'm told I've won the Turner. I was floored.'"[12]

The following year, he bought an abandoned Methodist church in Bellport, on Long Island, New York State, where he would live for the remainder of his life. Morley was granted American citizenship in 1990. He was the subject of museum exhibitions at venues including Tate Liverpool (1991); the Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (1993); Fundación La Caixa, Madrid (1995); the Hayward Gallery, London (2001); and the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (2013–14).

At the time of his death Morley resided in Bellport, New York, where he shared a home with Lida Morley, his wife since 1986. He died on 1 June 2018 at the age of 86, six days shy of his 87th birthday.[13]

Work

Morley's earliest work upon leaving art school, while remaining in England, adopted traditional, naturalist styles of painting. His work was "a compromise between old-school observation-based naturalism and art that was modern mostly because its subjects were recognizably of the present."[8]

After his arrival in New York, he began in the early 1960s to work abstractly, creating several paintings made up of only horizontal bands with vague suggestions of nautical themes, whether in imagery or in the works' titles.

He also met Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein and, influenced in part by them, made the drastic change to a photorealist style (Morley preferred the phrase Superrealist). Inspired by seeing Richard Artschwager using this technique, he began to use a grid to transfer photographic images (often of ships) to canvas, and became one of the first and most noted photorealists, along with Gerhard Richter, Richard Artschwager, and Vija Celmins.

After seeing one of Morley's paintings of an ocean liner, Artschwager suggested that Morley visit Pier 57 and paint some ships from life. "I went down to Pier 57, took a canvas and tried to make a painting outside," Morley said. "But it was impossible to comprehend it in one glance, one end is over there, the other end is over there, a 360 degree impossibility. I was in disgust—I took a postcard of this cruise ship called the Queen of Bermuda."[2] He would adopt this as his style for a few years, transposing images from a variety of sources (travel brochures, calendars, old paintings) to canvas. One factor that distinguished Morley from his photorealist peers was that rather than painting from the photograph itself, he was painting from printed reproductions such as postcards, sometimes even including the white border around a postcard image or the corporate logo from a calendar page.[8] His choice of these bland materials was partly driven by a desire to find pop-culture imagery that other artists, such as Warhol and Lichtenstein, were not already using: “What I wanted was to find an iconography that was untarnished by art."[2] Morley achieved "instant success" with such work.[4]

In the 1970s, Morley's work began to be more expressionist, with looser brushwork, and he began to incorporate collage and performance into his work, for example in 1972, when he was invited to paint a version of Raphael's The School of Athens at the State University of New York at Potsdam, in front of an audience[6]. He painted in costume as Pythagoras, who appears in the painting. When Morley realized that he failed to align one of the rows, he let the mistake stand in the finished work. His doing so serves as an example for one curator that the gridded reproduction technique is less concerned with faithful reproductions of the old masters and more with “untested possibilities of contemporary painting and pictorial construction.”[8]

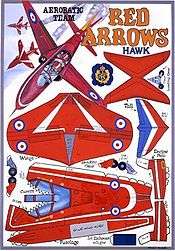

His work often drew upon various sources in a process of cross-fertilization. For example, his painting The Day of the Locust (1977) draws its title from the novel The Day of the Locust, by Nathanael West. One scene in the painting is drawn from the opening scene of the novel, and other scenes are drawn from the 1954 film Suddenly and the 1925 Sergei Eisenstein film Battleship Potemkin.[1] In the painting, the cover of a Los Angeles phone book is superimposed with a welter of imagery, some of it based on his earlier work (cruise ships, airplanes), and some on painted models, which became a mainstay of his subject matter for the remainder of his career. "I don't like to call them toys," the artist said, "I like to call them models. The thing about so-called 'toys' is that there is an unconsciousness in society that comes out in its toys. Toys represent an archetype of the human figure."[2]

The artist turned to new subjects, including mythology and the Classical world, in his work of the 1980s, giving his paintings titles like Aegean Crime (1987) and Black Rainbow Over Oedipus at Thebes (1988) and depicting Minoan figures; travel to the United States also resulted in prominent use of Native American kachina dolls and other motifs from those cultures. His commercial success offered him the opportunity to travel to these places and many more, resulting in diverse new influences and inspirations.[2] He frequently adopted very loose paint handling, featuring drips and splashes. Similar expressionist brushwork and subject matter by artists such as Julian Schnabel, Eric Fischl, Georg Baselitz, and Anselm Kiefer resulted in curators identifying a "neo-Expressionist" movement, in which they included him, although he disliked the label.

The 1990s saw the artist return to his very early subject matter of large seagoing vessels, often with the addition of fighter planes that he built out of paper, painted with watercolor, and then attached to the surface of the canvas (resulting in, as he told an interviewer, the pun of a "three-dimensional plane"[2]). In one example, Icarus's Flight (1997), the plane is some fifty-two inches deep[2]. The artist also branched out into full-on free-standing sculpture, with one piece, Port Clyde (1990), showing a boat on a window frame, as if referring back to the artist's lost childhood model of the HMS Nelson[2].

Contemporary photojournalism was the subject of the artist's paintings of the following decade, with motorcycle and car racing, football, skiing, swimming, and horse racing coming in for attention[14]. The artist also returned to the "catastrophes" that were among his early subjects, depicting car crashes (including one showing the crash that resulted in the death of auto racing star Dale Earnhardt), the aftermath of the War in Afghanistan, and the collapse of a building in Brooklyn, among other subjects. In the last decade of his life, Morley continued to depict early- and mid-twentieth-century fighter planes, as well as the pilots who flew them during World Wars I and II, including the legendary flying ace Manfred von Richthofen, the "Red Baron." He also focused on 18th-century English history, creating works that incorporated military figures such as Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington and Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson. "I fell in love with the period," he once said, "which was a great one for the British."[15]

Selected Works in Public and Private Collections

Cristoforo Colombo, 1966, Hall Foundation

Family Portrait, 1968, Detroit Institute of Arts

Coronation and Beach Scene, 1968, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Vermeer, Portrait of the Artist in His Studio, 1968, The Broad

Age of Catastrophe, 1976, The Broad

Day of the Locust, 1977, Museum of Modern Art

French Legionnaires Being Eaten by a Lion, 1984, Museum of Modern Art

Kristen and Erin, 1985, The Broad

Black Rainbow Over Oedipus at Thebes, 1988, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Man Overboard, 1994, Hall Foundation

Mariner, 1998, Tate

Painter’s Floor, 1999, Albright Knox Art Gallery

Theory of Catastrophe, 2004, Hall Foundation

Medieval Divided Self, 2016, Hall Foundation

Recognition

Selected Honors/Awards:

1984 Turner Prize, Tate Gallery, London, England

1992 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Painting Award

2009 Inductee, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Class IV: Humanities and Arts, Section 5: Visual and Performing Arts—Criticism and Practice

2011 Elected as Member, American Academy of Arts and Letters

2015 Francis J. Greenburger Award, Omi International Arts Center, Ghent, New York

Collections

Morley's work is included in public collections including:

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK

Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Oslo, Norway

Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht, Holland

Broad Foundation, Los Angeles, California

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, Michigan

Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, New York

Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

Kröller-Müller Museum, Netherlands

Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark

Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, Aachen, Germany

Ludwig Museum, Budapest, Hungary

Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Spain

Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Illinois

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Utrecht, Netherlands

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri

National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Orlando Museum of Art, Orlando, Florida

Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, New York

Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Rhode Island

Sammlung Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden, Germany

Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, Washington

Tate, London

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia

Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

References

- 1 2 Brooklyn Rail, March 2012

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Lebensztejn, Jean-Claude (2001). Malcolm Morley: Itineraries. London: Reaktion. p. 173. ISBN 1861890834. OCLC 45325239.

- ↑ Morley, Malcolm (October 31, 2007). "Tate lecture: Malcolm Morley". Tate.org. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Rosenthal, Norman (2013). Malcolm Morley at the Ashmolean: Paintings and Drawings from the Hall Collection. Oxford: Ashmolean. p. 16. ISBN 9781854442857.

- ↑ Lebensztejn, Jean-Claude (2001). Malcolm Morley: Itineraries. London: Reaktion Books. p. 17. ISBN 9781861890832.

- 1 2 3 1942–, Whitfield, Sarah, (2001). Malcolm Morley : in full colour. Hayward Gallery. London: Hayward Gallery. pp. 52–53. ISBN 1853322172. OCLC 48241555.

- ↑ Whitfield, Sarah (2001). Malcolm Morley in Full Color. London: Hayward Gallery. p. 136. ISBN 1853322172.

- 1 2 3 4 Storr, Robert (2012). Malcolm Morley in a Nutshell: The Fine Art of Painting, 1954–2012. Yale School of Art. p. 30.

- ↑ New York Magazine, February 20, 1984

- ↑ "documenta 5". Wikipedia. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ↑ "documenta 6". Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ↑ Higgins, Charlotte (September 8, 2007). "Malcolm Morley". The Guardian. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ↑ Malcolm Morley, Genre-Crossing Artist, Is Dead at 86

- ↑ Clearwater, Bonnie (2005). Malcolm Morley: The Art of Painting. North Miami, FL: Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami. p. 6. ISBN 1888708255.

- ↑ Wroe, Nicholas (October 4, 2013). "Malcolm Morley: 'The moment anyone said my work was art, I had this block – I took a long time to find myself'". The Guardian. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

External Links

- Malcolm Morley at Xavier Hufkens, Brussels

- Malcolm Morley at Sperone Westwater

- A Tribute to Malcolm Morley at the Brooklyn Rail

- Malcolm Morley in the Museum of Modern Art

- Malcolm Morley in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Malcolm Morley at Tate

- “Malcolm Morley: Works from the Hall Collection” at the Hall Foundation