Awwam

| محرم بلقيس | |

Ruins of Mahram Bilqis or Awam Temple in 1988 near Ma'rib, Yemen | |

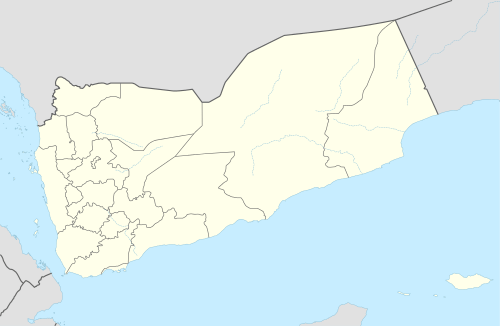

Shown within Yemen | |

| Location | Awwam, Ma'rib Governorate, Yemen |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 15°24′15″N 45°21′21″E / 15.404247°N 45.355705°ECoordinates: 15°24′15″N 45°21′21″E / 15.404247°N 45.355705°E |

| History | |

| Periods | Ancient Yemen |

| Satellite of | Almaqah |

Awwam (Old South Arabian: ʾwm;

One of the most frequent titles of the god Almaqah was "Lord of ʾAwwām".[1]

Temple of Awwam

The Temple of Awwam or "Mahram Bilqis" is a Sabaean temple dedicated to the principal deity of Saba, Almaqah, near Ma'rib in what is now Yemen. The temple is situated 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) southeast of ancient Marib, and was built in the city outskirt. Usually Sabaean major sanctuaries are located outside urban centers, the reason behind it, is probably for religious privacy, and to facilitate the conduct of rituals by arriving pilgrims from remote areas of Sabaean territories.[2] Such patterns are observed in several temples from Al-Jawf and the Hadramawt.

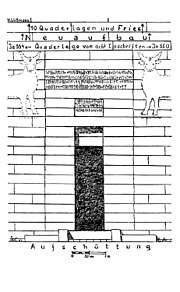

The oldest inscription found in the complex was in reference to the building of the temple's massive enclosure by Mukarrib Yada`'il Dharih I in the middle of the 7th century BC. Indicating much earlier period of the temple's construction. Yada`'il inscription was carved outside the wall, and contains the following:

Yadaʿʾil Dharih, son of Sumhuʾalay, mukarrib of Saba', walled ʾAwwam, the temple of Almaqah, when he sacrificed to Athtar and [when] he established the whole community [united] by a god and a patron and a pact and a [secret] trea[ty. By Athtar and by Hawbas and by] Almaqah.[3]

The largest part of the temple is occupied by an unguarded yard that is enclosed by a stone wall with an irregular oval ground plan. On the inner wall of the hall were several dozen highly important inscriptions from the late period of the Sabaean kingdom.

Partial excavation of Awwam peristyle in 1951-52 by the American Foundation for the Study of Man that was led by Wendell Philips, cleared the entrance court almost completely and made numerous discoveries. Such as elaborate bronze statues, and the usage of the southern entrance in the elliptic wall for ablution rituals before entering the cella.[4]

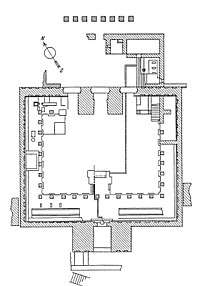

General plan of Awwam temple

The temple is situated in isolated area functioning mainly as religious sacred place. The place name, 'wm (place of refuge), signify that sacredness attached to the sanctuary. There is a possibility that the temple developed from a small shrine into an enormous complex encompassing multiple structures associated with the temple i.e. houses for priests, auxiliary rooms, workshops for metalworkers, cemetery connected to the sanctuary and residential area which make the so-called protected enclave. Geomorphological investigations have shown that the Awwam temple was erected on high natural platform, making it even more impressive for the viewers.

The temple itself was oriented towards the rising sun (north-east) and consisted of eight pillars propylaeum marking the entrance, followed by large rectangular peristyle hall, and massive oval shaped enclosure with other exterior linked structures (nearby cemetery). Pillars are the most widespread architectural feature used in ancient South Arabian religious structures. The peristyle hall might have reflected the numbers of the eight pillared propylaeum; There are thirty two pillars (4 x 8) inside the peristyle hall, and sixty four (8 x 8) fake recessed windows.

Bronze bull, horse, and human statues used to be attached to the entrance gates of the temple. Access to the complex was controlled by doors leading to hierarchical series of courtyards and halls that served as transitional areas.

Many aspects of the decoration, geometrical and figurine paintings, sculptures, large and precisely dressed stones, finely carved inscriptions painted red, and beautiful ornamental friezes on the wall's exterior, meant to impress the visitor and fill him with awe in the presence of god.

The peristyle hall

The hall has a semi-rectangular form, with eight monolith pillared propylaeum entrance topped by square tenons designed to accommodate an architrave. The perimeter of the peristyle hall is approximately 42 x 19 m and is flanked by the end of the oval-shaped enclosure in its western and eastern exterior walls. The interior of the structure contains a large library of inscribed stone blocks and 64 vertically fake double windows motif with 32 pillars made from single monolith except two that once supported stone beams.[5] Number eight might reflect a sacred number, since it is used at the entrance, interior pillars (8 x 4) and fake windows (8 x 8). Ancient South Arabian buildings, including Awwam peristyle hall, appears to be pre-planned according to advance system of measurement instead of fair using of space.[6] AFSM excavation in the paved courtyard revealed multiple South Arabian inscriptions, a group of broken column capitals, bronze plaques, altars, and numerous pottery statues,[7] along with potsherds that date back roughly to 1500-1200 BC.

Visitors of the sanctuary are obliged to go through the annex then via a gate of three entrances into the peristyle hall. The gate could be closed if needed.[8]

An observable water conduit made from alabaster used to run through the hall and into a bronze basin (69 x 200 cm) placed in a room for purification purposes. The water fell on the floor like a fountain, and it fell so long and with such force that it eventually cut through a copper basin placed under and then into the stone itself.

The oval shaped enclosure

The enclosure is defined by massive oval shaped wall that flank the peristyle hall from its western and eastern wings, the wall's length is measured approximately 757 m and 13 m in height, however the original height can't be determined for certainty and it's difficult to assess the real extent. Many inscriptions, hundreds in quantity, were discovered in the sanctuary and nearby, only few that deals directly with the temple's construction. One of the terminologies used for the sanctuary was "gwbn"; The oracle sanctuary. The sanctuary include a raised platform within the temple's sacred area representing primordial mound. Which makes it more impressive when looked from a distance. It appears, from archeological investigation, that a cultic place was built around a wellspring inside the sanctuary.

The oval sanctuary is accessible from two gates, either through the northwestern gate, or from the peristyle hall one, which was the main entrance, while the former was exclusively built for priests. Third gate was discovered by AFSM, but it was for the cemetery and accessed only from the interior of the oval sanctuary and restricted to funerary rites usage.

The oval sanctuary precinct was the main and holy part of Awwam temple. It was an open space that contains several structures, courtyards, and wellspring. Most rituals were performed in the oval sanctuary, and according to Sabaean inscriptions, was the house of Almaqah. This holiness is demonstrated by the existence of three places for purification and to perform ablutions before entering the sacred spaces, primarily the oval sanctuary (dwelling house of Almaqah). Cleanness is emphasized by the discovered inscriptions that deals with physical and spiritual purity of worshipers. Several inscriptions attest that an individual who enter the sanctuary without performing purification rituals, will suffer severe consequences. Although no detailed information concerning the act of purification is mentioned in Sabaean inscriptions.

The cemetery

The 7th century BC cemetery is attached to the Oval Sanctuary, and apparently accessed only from it. The cemetery hosts around 20,000 estimated burials during its long period of usage. That lengthy period created a large settlement of the dead, where passages and streets divide the tombs. The cemetery tombs were multi-storey structures (up to four) built using excellently polished and dressed limestone blocks. External walls were sometimes decorated with friezes and low relief of the dead's face.

According to south Arabian inscriptions the cemetery was known as "Mhrm Gnztn" (cemetery sacred enclave). Despite the sacredness of the cemetery, no surplus of epigraphic remains for the ritual ceremonies were found in the complex. Apparently the rituals were conducted in the Oval Sanctuary Precinct, then they enter the cemetery where further ceremonies took place before burial.[9]

The memory of the dead was preserved by placing sculptural representations of them on their tombs, frequently inscribing their names.

See also

Literature

- Le Baron Bowen Jr., Richard; Albright, Frank P. (1958). Archaeological Discoveries in South Arabia. Publications of the American Foundation for the Study of Man. 2. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins. OCLC 445765.

- Korotayev, Andrey (1996). Pre-Islamic Yemen: Socio-political organization of the Sabaean cultural area in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 3-447-03679-6.

- Müller (Hrsg.), Walter W.; von Wissmann, Hermann (1982). Das Grossreich der Sabäer bis zu seinem Ende im frühen 4. Jahrhundert vor Christus. Die Geschichte von Saba'II [The United Kingdom of the Sabeans to its end in the early 4th century BC. The history of Saba'II]. Sitzungsberichte [Meeting notes]. Philosophisch-historische Klasse (in German). 402. Wien: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften [ Austrian Academy of Sciences]. ISBN 3-7001-0516-9.

References

- ↑ A. V. Korotaev (1996). Pre-Islamic Yemen: Socio-political Organization of the Sabaean Cultural Area in the 2nd and 3rd Centuries AD. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 82. ISBN 978-3-447-03679-5.

- ↑ Robin, 1996

- ↑ James B. Pritchard; Daniel E. Fleming (28 November 2010). The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton University Press. p. 313. ISBN 0-691-14726-4.

- ↑ Geoffrey W. Bromiley (1979). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-8028-3781-3.

- ↑ Albright 1952, P. 26-28

- ↑ Doe, Brian, Architectural refinement and measure in early South Arabian buildings. PSAS. Vol (12) London, 1985, P. 22-23

- ↑ Albright 1952, P. 269-275

- ↑ Zaid & Marqten 2008: P. 228-240

- ↑ Roring 2005, P. 153-159