Macanao Peninsula Municipality

| Península de Macanao Municipality Municipio Península de Macanao | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | |||

| |||

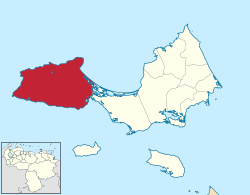

Location in Nueva Esparta | |||

.svg.png) Península de Macanao Municipality Location in Venezuela | |||

| Coordinates: 11°00′06″N 64°18′57″W / 11.001692°N 64.315731°WCoordinates: 11°00′06″N 64°18′57″W / 11.001692°N 64.315731°W | |||

| Country |

| ||

| State | Nueva Esparta | ||

| Municipal seat | Boca del Río | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 330.7 km2 (127.7 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2001) | |||

| • Total | 20,935 | ||

| • Density | 63/km2 (160/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | UTC−04:00 (VET) | ||

| Website | Official website | ||

The Macanao Peninsula is a geographic peninsula landform, that forms the western end of the Isla Margarita in the Caribbean Sea, in northern Venezuela.

It is also a Venezuelan municipality, the Municipality of Macanao Peninsula (Municipio Península de Macanao), in the state of Nueva Esparta. The municipal seat is Boca de Río.

Geography

The peninsula is connected to the rest of Isla Margarita by a thin strip of land in Laguna de la Restinga National Park. Sixty years ago, it was an island. [1] The peninsula has an area of 330 square kilometres (130 sq mi), rising from sea level to 745 metres (2,444 ft) at the peak of Cerro Macanao.[2] A ridge of high land runs along the peninsula from east to west.[3] The main east-west crest is sharp and narrow.[4] The mountains are smaller than in Maragarita, but are much more rugged, with many steep-sided valleys cutting through the mountain sides.

The more remote beaches can only be reached via dirt roads.[5]

The climate of Margarita as a whole is hot and tropical, with little rainfall. The Macanao peninsula is particularly arid and dry.[6] In the 1950s, the mountains in the central range were forested up to about 650 metres (2,130 ft).[7] Vegetation today is mainly open cactus-chaparral, with deciduous forests in the seasonal riverbeds.[2]

The mean average temperature is 27 °C (81 °F), and mean annual rainfall is 500 millimetres (20 in). Trade winds blow from the northeast, so rainfall is highest on the northern side.[2]

Geology

Macanao Peninsula is relatively newly formed. In the northern part of the peninsula, littoral deposits from the early Pleistocene form a terrace 30 metres (98 ft) high made of a sandy marl 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) that contains the bivalves Lyropecten arnoldi. In the south, a littoral terrace 18 to 21 metres (59 to 69 ft) high dates to the mid-Pleistocene, and calcareous clays from the Late Pleistocene form a terrace 10 to 12 metres (33 to 39 ft) high. There are many raised beaches from the Holocene.[8]

The highlands of the peninsula contain amphibolite and eclogite mafic rocks which, like tholeiitic metabasalt, are similar to the rocks found both on island arcs and on mid-ocean ridges.[9]

People

Admiral Garcia Álvarez de Figueroa, governor of Margarita Province between 1626 and 1630, was known for his enjoyment of the trade in pearls from Cubagua and the Macanao peninsula.[10] The Guayqueria Indians are indigenous to the island. When Alexander von Humboldt visited in 1799 he was met by eighteen Guayqueria men. He described them as "of very tall stature. They had the appearance of great muscular strength, and the colour of their skins was something between a brown and a copper colour."[11] As of 1964, the population was about 6,500, living in five hamlets. Water was delivered by barge at no charge, but with only a few liters per capita for all uses.[12]

Tourism

The Macanao peninsula is sparsely populated. Tourists may take horseback rides, or visit picturesque beaches with fishing boats, such as Punta Arenas.[13] The La Pared beach is pleasant and little used. Divers prefer Punta Arenas beach at the far west, where the water is warmest and where giant starfish may be found.[1]

Macanao is also the best part of the island for mountain biking for those prepared to handle the intense sun.[14]

The largest town is Boca de Río, which has a marine museum, This includes the skeleton of a whale, displays of boats, fish, corals, pearls and turtles, and a shallow aquarium with catsharks and sea turtles.

Environmental concerns

Isla Maragarita is the largest of the Venezuelan Caribbean islands, and the most biologically diverse. The only protected area is a small part of Laguna de La Restinga National Park. The proposed Macanao Wildlife Reserve, containing the Chacaracual Community Conservation Area (CCCA), may provide better protection.[15]

Conservation threats include high levels of illegal hunting and trafficking of wildlife and plants, and open cast mining.[15]

The peninsula is the only home of the endangered yellow-shouldered amazon parrot, and is also home to the blue-crowned parakeet. The seasonal watercourses, or quebradas, are the main nesting and feeding grounds for the yellow-shouldered amazon. They are being mined for sand and gravel to be used in construction, and in some areas the parrot is hunted, considered a pest that robs jocote orchards.[16]

Gallery

View west towards La Restinga Lagoon National Park and Macanao Peninsula.

View west towards La Restinga Lagoon National Park and Macanao Peninsula. Opuntia cactus on the Macanao Peninsula.

Opuntia cactus on the Macanao Peninsula. Transport in La Restinga Lagoon National Park.

Transport in La Restinga Lagoon National Park.

References

Citations

- 1 2 Auzias & Labourdette 2009, p. 354.

- 1 2 3 Akcakaya et al. 2004, p. 363-364.

- ↑ Blunt 1833, p. 439.

- ↑ Parsons 1956, p. 94.

- ↑ Greenberg 1997, p. 140.

- ↑ Gill et al. 2010, p. 778.

- ↑ Parsons 1956, p. 111.

- ↑ Richards 1974.

- ↑ Lallemant & Sisson 2005, p. 146.

- ↑ 1 de Junio de 1626.

- ↑ Humboldt, Bonpland & Williams 1815, p. 255.

- ↑ United Nations 1964, p. 287-288.

- ↑ Macanao.

- ↑ Gill et al. 2010, p. 782.

- 1 2 Dry Forests of Margarita Island.

- ↑ Snyder 2000, p. 105.

Sources

- "1 de Junio de 1626". Fodeapemine. Government of Venezuela. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- Akcakaya, H. Resit; Burgman, Mark A.; Kindvall, Oskar; Wood, Chris C.; Sjogren-Gulve, Per; Hatfield, Jeff S.; McCarthy, Michael A. (2004-10-07). Species Conservation and Management:Case Studies includes CD-ROM: Case Studies includes CD-ROM. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516646-0.

- Auzias, Dominique; Labourdette, Jean-Paul (2009-11-18). Vénézuela. Petit Futé. ISBN 978-2-7469-3431-3. Retrieved 2012-08-31.

- Blunt, Edmund March (1833). The American coast pilot: containing directions for the principal harrours [!] capes, and headlands, on the coast of North and South America ... with the prevailing winds, setting of the currents, &c., and the latitudes and longitudes of the principal harbours and capes; together with a tide table. E. and G.W. Blunt. Retrieved 2012-08-31.

- "Dry Forests of Margarita Island, Venezuela". World Land Trust. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- Gill, Nicholas; Greenspan, Eliot; O'Malley, Charlie; Pashby, Christie; Perilla, Jisel; Schlecht, Neil E.; Blore, Shawn; de Vries, Alexandra (2010-06-28). Frommer's South America. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-59155-0. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- Greenberg, Arnold (1997-10-01). Venezuela Alive. Hunter Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-1-55650-800-4. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- Humboldt, Alexander von; Bonpland, Aimé; Williams, Helen Maria (1815). Personal narrative of travels to the equinoctial regions of the New Continent during the years 1799-1804 by Alexander de Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland. M. Carey. Retrieved 2012-08-31.

- Lallemant, Hans G. Avé; Sisson, Virginia Baker (2005). Caribbean-South American Plate Interactions, Venezuela. Geological Society of America. ISBN 978-0-8137-2394-5. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- "Macanao". venezuelatuya.com. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- Parsons, James Jerome (1956). San Andrés and Providencia: English-speaking islands in the western Caribbean. University of California Press. Retrieved 2012-08-31.

- Richards, Horace Gardiner (1974). Annotated Bibliography of Quaternary Shorelines: Second Supplement 1970-1973. Academy of Natural Sciences. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-4223-1777-8. Retrieved 2012-08-31.

- Snyder, Noel F. R. (2000). Parrots: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan 2000-2004. IUCN. p. 105. ISBN 978-2-8317-0504-0. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- United Nations, Dept. of Economic and Social Affairs. Resources and Transport Division (1964). Water desalination in developing countries. United Nations. Retrieved 2012-08-31.

.png)