Low-background steel

Low-background steel is any steel produced prior to the detonation of the first atomic bombs in the 1940s and 1950s. With the Trinity test and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, and then subsequent nuclear weapons testing during the early years of the Cold War, background radiation levels increased across the world. Modern steel is contaminated with radionuclides because its production uses atmospheric air. Low background steel is so called because it does not suffer from such nuclear contamination. This steel is used in devices that require the highest sensitivity for detecting radionuclides.

The primary source of low-background steel is ships that were constructed before the Trinity test, most famously the scuttled German World War I battleships in Scapa Flow.[1]

Radionuclide contamination

From 1856 until the mid 20th century, steel was produced in the Bessemer process where air was forced into Bessemer converters converting the pig iron into steel. By the mid-20th century, many steelworks had switched to the BOS process which uses pure oxygen instead of air. However as both processes use atmospheric gas, they are susceptible to contamination from airborne particulates. Present-day air carries radionuclides, such as cobalt-60, which are deposited into the steel giving it a weak radioactive signature.[4]

World anthropogenic background radiation levels peaked at 0.15 mSv/yr above natural levels in 1963, the year that the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty was enacted. Since then, anthropogenic background radiation has decreased exponentially to 0.005 mSv/yr above natural levels.[5]

There have been incidents of radioactive cobalt-60 contamination as it has been recycled through the scrap metal supply chain.[6]

Necessity

Devices that require low-background steel include:

- Geiger counters

- Medical apparatus: whole body counting and lung counters

- Scientific equipment: photonics

- Aeronautical and space sensors

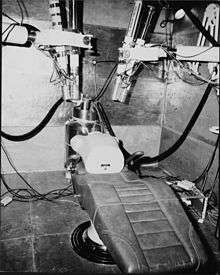

As these devices detect radiation emitted from radioactive materials, they require an extremely low radiation environment for optimal sensitivity. Low background counting chambers are made from low-background steel with extremely heavy radiation shielding. They are used to detect the minutest nuclear emissions.[7]

References

- ↑ Butler, Daniel Allen (2006). Distant Victory: the Battle of Jutland and the Allied Triumph in the First World War. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Security International (Greenwood Publishing Group). p. 229. ISBN 0-275-99073-7.

- ↑ "Russian Health Studies Program – Joint Coordinating Committee for Radiation Effects Research (JCCRER)". United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ↑ The Mayak Production Association, a Russian nuclear facility

- ↑ Adams, Cecil (December 10, 2010). "Is steel from scuttled German warships valuable because it isn't contaminated with radioactivity?". The Straight Dope.

- ↑ United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) (2010), Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation (UNSCEAR 2008 Report): Volume I, New York: United Nations, p. 6, ISBN 978-92-1-142274-0,

The estimated per caput effective dose of ionizing radiation due to global fallout from atmospheric nuclear weapons testing was highest in 1963, at 0.11 mSv/yr, and subsequently fell to its present level of about 0.005 mSv/yr (see figure II). This source of exposure will decline only very slowly in the future as most of it is now due to the long-lived radio-nuclide carbon-14.

- ↑ Reducing Risks in the Scrap Metal Industry – Sealed Radioactive Sources (PDF) (IAEA/PI/A.83 / 05-09511), Austria: International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), September 2005, pp. 2–6, archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2006

- ↑ Aaron, D. Jayne; Berryman, Judith (1997). "Rocky Flats Plant, Emergency Medical Services Facility – HAER No. CO-83-S (Rocky Flats Plant, Building 122)". U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management.