Lost Padre mine

The Lost Padre mine is a lost mine believed to be located in Southern California, within the borders of the San Emigdio municipality in Northern Ventura County.[1]

History

According to historical accounts, the Lost Padre mine was created and operated by Catholic missionaries and Native Americans.[2] It is believed that the mine was in operation anywhere between the late 17th and early 19th century. However, earlier estimates are likely to be more accurate, due to indications that the Jesuit priests who funded the creation of the mine were dignitaries of Spain or Mexico.

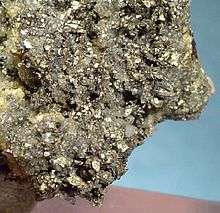

The mine is reportedly home to large deposits of unrefined gold and silver, coming from veins of quartz pushed into the Southern California mountains by glaciers roughly 1.8 million years ago.[3] In addition, it is believed that the bodies of as many as 20 workers, mostly Native Americans, were buried in a cave-in. Upon its reported rediscovery in the 1800s, many of those seeking to return to the mine were killed in riding accidents on the way to the mine, either being thrown from their horses or falling down the cliffs of the San Emigdio region.

Twentieth century

Throughout the 20th century, several groups have searched for the mine. The most notable and prominent example is the Edwards family. John Edwards has become the primary source of researchers, as his father and grandfather were both reportedly experts on the topic. Edwards' grandfather had reportedly rediscovered the mine shortly after World War I, only disclosing its general vicinity within Doc Williams Canyon,[4] near Eagle Rest Peak in the mountains of Kern County.

Recent

The most recent attempt at rediscovery is by Jake Allard, a local college student of Anthropology at Moorpark College. Allard has claimed to have made a total of 6 expeditions in the regions described by Edwards, following the San Emigdio Creek through the various canyons. During the most successful expedition, he was accompanied by three colleagues from Moorpark College and Carnegie Mellon University. The former include colleagues Austin Clarizio, Collin Chamberlain, and Roman Kaufman.

Allard believes the vicinity outlined by Edwards is the only feasible option, based on clues and context given in historical records, including nearby veins of silver and quartz, as well as gold dust discovered during the search. Artifacts discovered by Allard back up this claim. These include a late 18th or mid 19th-century mining tool, although its origins have not been confirmed.[5][6]

Hundreds of hours of charting and mapping have resulted in the location of the mine being narrowed down to roughly 8 square miles. As of May 2017, Jake Allard has discovered one physical mine in the vicinity of Eagle Rest Peak.[7] Despite not being a part of the Lost Padre mine, it shows promise that an exposed vein of ore may be within a reasonable distance. Allard argues that an open pit mining operation would be the most probable structure of the mine, given the location and time it was operated.

Red Rock Canyon Mine

Some theories suggest the Red Rock Canyon mine, located near Castaic, is actually an offshoot vein of the Lost Padre mine. However, there are several issues with this claim. The Red Rock mine, for example, was discovered in the 19th century and worked until 1935, over one hundred years after the Lost Padre mine was said to be in operation.[8] Some, including Jake Allard, dispute this claim, having mapped a path to the Red Rock mine in 2016 in an attempt to collect evidence of late Mexican or early American creation of the Red Rock Canyon mine, as opposed to by Jesuit missionaries.

In popular culture

A film has been produced, entitled Lost Padre Mine, directed by David Noble. The film centers on the legend of the Lost Padre mine, following the character of Wayne Braddock, a treasure hunter who arrives in El Paso in search of missing gold.[9]

References

- ↑ "The Ridge Route Communities Historical Society: Local Mining History". Retrieved 2017-04-07.

- ↑ Hudnall, Wang, Ken, Connie. Spirits Of The Border: The History And Mystery Of Ft. Bliss Texas. p. 14. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ↑ "Glaciers of California | Glaciers of the American West". glaciers.research.pdx.edu. Retrieved 2016-09-27.

- ↑ "Doc Williams Canyon Topo Map, Kern County CA (Eagle Rest Peak Area)". Retrieved 2016-09-27.

- ↑ "Ventura | Society for California Archaeology". scahome.org. Retrieved 2016-09-27.

- ↑ "Mining Artifacts". miningartifacts.homestead.com. Retrieved 2016-09-27.

- ↑ "Jake Allard on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved 2017-05-27.

- ↑ "Gold Mines of Los Angeles County". www.lagoldmines.com. Retrieved 2016-09-27.

- ↑ Lost Padre Mine (2017), retrieved 2017-05-27