Lost Boundaries

| Lost Boundaries | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Alfred L. Werker |

| Produced by | Louis De Rochemont |

| Written by |

William L. White (story) Charles Palmer (adaptation) Eugene Ling Virginia Shaler Furland de Kay (add. dialogue) |

| Starring |

Beatrice Pearson Mel Ferrer Susan Douglas Rubeš |

| Cinematography | William Miller |

| Edited by | Dave Kummins |

| Distributed by | Film Classics |

Release date |

|

Running time | 99 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $2 million[2] |

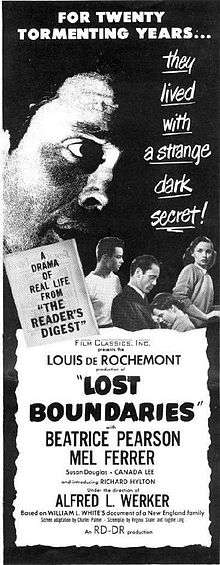

Lost Boundaries is a 1949 American film directed by Alfred L. Werker that stars Beatrice Pearson, Mel Ferrer (in his first starring role), and Susan Douglas Rubeš. The film is based on William Lindsay White's book of the same title, a nonfiction account of Dr. Albert C. Johnston and his family, who passed for white while living in New England in the 1930s and 1940s. The film won the 1949 Cannes Film Festival award for Best Screenplay.[3]

Plot

In 1922, Scott Mason Carter graduates from Chase Medical School in Chicago and marries Marcia. Both are light-skinned enough to be mistaken for whites. Scott has landed an internship, but his fellow graduate, the dark-skinned Jesse Pridham, wonders if he will have to work as a Pullman porter until there is an opening in a black hospital.

When Scott goes to Georgia, the black hospital director tells him that the board of directors has decided to give preference to Southern applicants and rescinds the job offer. The couple live in Boston with Marcia's parents, who have been passing as white. Her father and some of their black friends suggest they do the same. Instead, Scott continues to apply as a Negro and is repeatedly rejected. Scott finally yields, quits his job making shoes, and masquerades as white for a one-year internship in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

There, Scott responds to an emergency. At an isolated lighthouse, he has to operate immediately on a sport fisherman who is bleeding to death. His patient turns out to be Dr. Walter Bracket, the well-known director of a local clinic. Impressed, Dr. Bracket offers Scott a position as town doctor in Keenham (a fictionalized version of Keene, New Hampshire), replacing Bracket's recently deceased father. Scott declines, explaining that he is a Negro. Dr. Bracket, though he admits he would not have made the offer had he known, recommends Scott take the job without revealing his race. With his wife pregnant, Scott reluctantly agrees. Scott and Marcia are relieved when their newborn son appears as white as they do.

Scott slowly gains the trust and respect of the residents. By 1942, when the United States enters World War II, the Carters are pillars of the community. Their son, Howard, attends the University of New Hampshire, while daughter Shelly is in high school. Scott goes to Boston once a week to work at the Charles Howard Clinic, which Jesse Pridham and he established for patients of all races.

The Carters have kept their secret even from their own children. When Howard invites a black classmate, Arthur Cooper, to visit, Shelly worries aloud what her friends will think about a "coon" staying in their home. Scott sternly orders her never to use that word again. When Arthur goes to a party with Howard, some guests make bigoted remarks behind his back.

Scott and Howard enlist in the Navy, but after a background check, Scott's commission as a lieutenant commander is suddenly revoked for "failure to meet physical conditions". The only position open to blacks in the Navy is steward. The Carters have no choice but to tell their children the truth. Howard breaks up with his white girlfriend. He rents a room in Harlem and roams the streets. When Shelly's boyfriend Andy asks her about the "awful rumor" about her family, Shelly confesses that it is true. He asks her to the school dance anyway, but she turns him down. In Harlem, Howard investigates screams and finds two black men fighting. When one pulls out a gun, Howard intervenes. The gun goes off and the gunman flees, but Howard is taken into custody. To a sympathetic black police lieutenant, Howard explains, "I came here to find out what it's like to be a Negro." Arthur Cooper collects his friend from the police station.

Howard and his father return to Keene. When they attend their regular Sunday church service, the minister preaches a sermon of tolerance, then notes that the Navy has just ended its racist policy. The narrator announces that Scott Carter remains the doctor for a small New Hampshire town.

Cast

The cast of Lost Boundaries is listed in order as documented by the American Film Institute.[1]

- Beatrice Pearson as Marcia Carter

- Mel Ferrer as Scott Carter

- Susan Douglas as Shelly Carter

- Rev. Robert A. Dunn as Rev. John Taylor

- Richard Hylton as Howard Carter

- Grace Coppin as Mrs. Mitchell

- Seth Arnold as Clint Adams

- Parker Fennelly as Alvin Tupper

- William Greaves as Arthur Cooper

- Leigh Whipper as Janitor

- Maurice Ellis as Dr. Cashman

- Edwin Cooper as Baggage man

- Carleton Carpenter as Andy

- Wendell Holmes as Morris Mitchell

- Ralph Riggs as Loren Tucker

- Rai Saunders as Jesse Pridham

- Morton Stevens as Dr. Walter Brackett

- Alexander Campbell as Mr. Bigelow

- Royal Beal as Detective Staples

- Canada Lee as Lt. Thompson

Sources

William Lindsay White, a former war correspondent who had become editor and publisher of the Emporia Gazette, published Lost Boundaries in 1948.[4] It was just 91 pages long, and a shorter version had appeared the previous December in Reader's Digest.[5][6] The story was also reported with photographs in Life, Look, and Ebony.[7] White recounted the true story of the family of Dr. Albert C. Johnston (1900–1988)[8] and his wife Thyra (1904–1995),[9] who lived in New England for 20 years, passing as white despite their Negro backgrounds until they revealed themselves to their children and community.

Lost Boundaries focuses on the experience of their eldest son, Albert Johnson, Jr., beginning with the day Albert, Sr., tells his 16-year-old son that he is the son of Negroes who have been passing as white. The story then recounts the lives of the parents. Dr. Johnston graduates from the University of Chicago and Rush Medical College, but finds himself barred from internships when he identifies himself as Negro. He finally secures a position at Maine General Hospital in Portland, which had not inquired about his race. In 1929, he establishes a medical practice in Gorham, New Hampshire. His blue-eyed, pale-skinned wife Thyra and he are active in the community, and no one suspects their racial background, at least not enough to comment on it or question them. In 1939, they move to Keene, New Hampshire, where he takes a position at Elliot Community Hospital. At the start of World War II, he applies for a Navy post as a radiologist, but is rejected when an investigation reveals his racial background. Struck by this rejection, he then shares his and his wife's family history with his eldest son Albert, who responds by isolating himself from friends and failing at school. Albert joins the Navy, still passing as white, but is discharged as "psychoneurotic unclassified". Albert then tours the U.S. with a white schoolfriend, visiting relatives and exploring lives on either side of the color line.[10] Much of the book is devoted to Albert Jr.'s personal exploration of the world of passing, where he learns how the black community tolerates its members who pass, but disapproves of casual crossing back and forth between the black and white communities. The other Johnson children have their own problems adjusting to their new identity and the acceptance and rejection they experience. Finally, Albert Jr., attending the University of New Hampshire, tells his seminar on international and domestic problems "that perhaps he could contribute something to this discussion of the race problem by telling of the problem of crossbred peoples because he was himself a Negro."

The film adaptation does not follow the younger Johnson on his exploration of the broader racial landscape, but instead the son in the film visits Harlem, where he witnesses lives lived in the street rather than in the private homes of his New Hampshire environment and becomes involved in violence. The film ends on a note of interracial reconciliation as the white population excuses the Johnstons' deception without examining the economic social pressures that led them to pass as white. The film, in one critic's analysis, presents a subject of racial violence and social injustice within the bounds of a family melodrama.[11]

Casting and production

Producer Louis de Rochemont was originally to have worked on the film under contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Because they could not agree on how to treat the story, with de Rochemont insisting on working "in the style of a restaged newsreel",[12] he mortgaged his home and developed other sources of financing so he could work independently.[13] Its status as an independent production led some theaters and audiences to view it as an art film, and art houses proved significant in the film's distribution.[12] De Rochement recruited local townspeople and found a local pastor to play the role of the minister.[13]

Filming took place on location in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Kittery, Maine,[14] Kennebunkport, Maine, and Harlem, New York.[13] Mel Ferrer accepted his role reluctantly, at a point in his career when he hoped to direct either theater or film.[15] The leading roles were all cast with white actors, so the film does not present any instances of racial passing, nor of interracial intimacy,[11] but the white actors chosen were unknown to the public to support the uncertain nature of their backgrounds in the film.

Reception

The film premiered in New York on June 30, 1949,[1] and screened in Keene, New Hampshire, on July 24, 1949.[16]

The Screen Directors Guild awarded Werker its prize for direction for the third quarter of 1949.[17]

Atlanta banned the film under a statute that allowed its censor to prohibit any film that might "adversely affect the peace, morals, and good order of the city".[18][19] Memphis did so as well, with the head of the Board of Censors saying: "We don't take that kind of picture here."[20]

Walter White, executive director of the NAACP, reported his reaction to viewing a rough cut of the film: "One thing is certain–Hollywood can never go back to its old portrayal of colored people as witless menials or idiotic buffoons now that Home of the Brave and Lost Boundaries have been made..."[21] The Washington Post countered attempts on the part of some in the South to deny that the film represented an actual social phenomenon by calling it "real life drama" and "no novel" that presented "the stark truth, names, places and all".[22] In The New York Times, critic Bosley Crowther said it had "extraordinary courage, understanding and dramatic power."[16]

Ferrer later said: "This was a very, very radical departure from any kind of fiction film anybody was making in the country. It was a picture which broke a tremendous number of shibboleths, and it established a new freedom in making films."[16]

In 1986, Walter Goodman located Lost Boundaries within the Hollywood film industry's treatment of minorities:[23]

As the 40's turned into the 50's, blacks belatedly made it to star status as victims. Although they tended to be pictured as either infallibly noble (Intruder in the Dust) or incredibly good looking (Sidney Poitier in No Way Out) or ineffably white (Mel Ferrer in Lost Boundaries and Jeanne Crain in Pinky), it was a beginning, and Hollywood must be credited with helping to create the consensus that produced the civil rights legislation of the 1960's.... It is futile to lament that commercial movies tend to be a trifle late and a trifle cowardly in handling contentious subjects. The important thing is that when they weigh in, they are usually for the underdog - and that's what happened here.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Lost Boundaries". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-02-20.

- ↑ "Top Grossers of 1949". Variety. 4 January 1950. p. 59.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: Lost Boundaries". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved January 9, 2009.

- ↑ White, W.L. (1948). Lost Boundaries. NY: Harcourt, Brace, & World, Inc. pp. 3–91.

- ↑ White, Walter (March 28, 1948). "On the Tragedy of the Color Line" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ↑ Shaloo, J.P. (July 1948). "Review". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 258: 170–1. JSTOR 1027803.

- ↑ Hobbs. A Chosen Exile. pp. 241–5.

- ↑ "Albert Johnston, 87, Focus of Film on Race". New York Times. June 28, 1988. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ↑ Thomas, Jr., Robert McG. (November 29, 1995). "Thyra Johnston, 91, Symbol of Racial Distinctions, Dies". New York Times. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ↑ Hobbs, Allyson (2014). A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life. Harvard University Press. pp. 226ff.

- 1 2 Lubin, Alex (2005). Romance and Rights: The Politics of Interracial Intimacy, 1945-1954. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 59–63.

- 1 2 Wilinsky, Barbara (2001). Sure Seaters: The Emergence of Art House Cinema. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 29, 73. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Pryor, Thomas M. (June 26, 1949). "Hoeing His Own Row" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ↑ "Of Local Origin" (PDF). New York Times. June 15, 1949. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ↑ Colton, Helen (September 4, 1949). "Reluctant Star" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Lillard, Margaret (July 25, 1989). "Landmark '49 Film About Family Passing for White Recalled". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ↑ Brady, Thomas F. (January 10, 1950). "Al Werker Wins Director's Prize" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ↑ Doherty, Thomas Patrick (2007). Hollywood's Censor: Joseph I. Breen & the Production Code Administration. Columbia University Press. p. 243. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ↑ McGehee, Margaret T. (Autumn 2006). "Disturbing the Peace: 'Lost Boundaries', 'Pinky', and Censorship in Atlanta, Georgia, 1949-1952". Cinema Journal. 46 (1): 23–51. doi:10.1353/cj.2007.0002. JSTOR 4137151.

- ↑ Hobbs. A Chosen Exile. pp. 254–8.

- ↑ Doherty. Hollywood's Censor. pp. 240–1.

- ↑ Hobbs. A Chosen Exile. p. 257.

- ↑ Goodman, Walter (April 27, 1986). "Ethnic Humor Bubbles to the Surface of the Melting Pot". New York Times. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

External links

- Lost Boundaries on IMDb

- Lost Boundaries at the TCM Movie Database

- Lost Boundaries at AllMovie

- Louis de Rochemont -- The Making of Lost Boundaries

- Louis de Rochemont -- Lost Boundaries

- Photo: Ferrer, Hylton, and Pearson, "Clips from three dramas arriving on Broadway this week", New York Times, June 26, 1949