Looking for Alaska

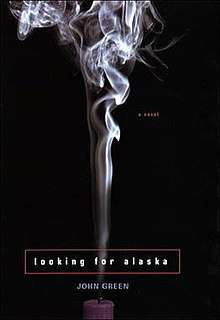

Looking for Alaska first edition cover | |

| Author | John Green |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Nolan Gadient |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Young adult novel |

| Publisher | Dutton Juvenile |

Publication date | 2005 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 223 |

| ISBN | 0-525-47506-0 |

| OCLC | 55633822 |

| LC Class | PZ7.G8233 Lo 2005 |

Looking for Alaska is John Green's first novel, published in March 2005 by Dutton Juvenile. It won the 2006 Michael L. Printz Award from the American Library Association,[1] and led the association's list of most-challenged books in 2015 due to profanity and sexually explicit scenes.[2] Looking for Alaska is inspired by Green's own experiences as a high school student. The story is told through the first-person narration of teenager Miles "Pudge" Halter, as he enrolls in a boarding school in order to "seek a Great Perhaps", in the words of François Rabelais. Pudge meets one student in particular, the erratic Alaska Young, whom he falls in love with as she guides him through his own "labyrinth of suffering" until he is forced to continue this spiritual journey on his own.

Background

The novel is heavily based off John Green's early life. As he explains, "I myself was once a guy from Florida who was obsessed with the dying words of famous people and then left home to attend a boarding school in Alabama."[3] He goes on to explain that while the novel is fictional, the setting is not. Green attended Indian Springs School, a boarding and day school outside of Birmingham, Alabama. Culver Creek of Looking for Alaska is Indian Springs School. From the smoking hole to the swing Pudge and Alaska sat on, John Green based the entire setting off of his high school. Characters are loosely based on his high school experiences, including smoking cigarettes in the woods instead of going to class.[3][4] While he was enrolled there, a student died under circumstances similar to the character of Alaska, which inspired the plot of the novel.[5][6]

John Green discussed at a book talk in Rivermont Collegiate on October 19, 2006 that he got the idea of Takumi's "fox hat" from a Filipino friend who wore a similar hat while playing pranks at Indian Springs School. From the same book talk, Green also stated that the possessed swan in Culver Creek came from his student life at Indian Springs School as well, where there was also a swan of similar nature on the campus. The two pranks that occur in the book are similar to pranks that Green pulled at his high school.[7] Green has also stated that several of Culver Creek's teachers are direct caricatures of multiple faculty members at Indian Springs.

During the week of July 29, 2012, Looking for Alaska broke into the New York Times best seller list at number ten in Children's Paperback, 385 weeks (more than seven years) after it was released.[8] As of May 3, 2016, it is number four on the New York Times best seller listing for Young Adult Paperback.[9] It spent eighteen weeks at number four.[10] Despite its literary success, Looking For Alaska has often been challenged in public school districts for content considered inappropriate.[11]

Plot

Miles Halter, obsessed with last words, leaves Florida to attend Culver Creek Preparatory High School in Alabama for his junior year, quoting François Rabelais's last words: "I go to seek a Great Perhaps".[12] Miles' new roommate, Chip "The Colonel" Martin, nicknames Miles "Pudge" and introduces Pudge to his friends: hip-hop emcee Takumi Hikohito and Alaska Young, a beautiful but emotionally unstable girl. Learning of Pudge's obsession with famous last words, Alaska informs him of Simón Bolívar's: "Damn it. How will I ever get out of this labyrinth!"[13] The two make a deal that if Pudge figures out what the labyrinth is, Alaska will find him a girlfriend. Alaska sets Pudge up with a Romanian classmate, Lara. Unfortunately, Pudge and Lara have a disastrous date, ending with a concussed Pudge throwing up on Lara. Alaska and Pudge grow closer and he begins to fall in love with her, although she insists on keeping their relationship platonic because she has a boyfriend that she insists she loves.

On his first night at Culver Creek, Pudge is kidnapped and thrown into a lake by the "Weekday Warriors," rich schoolmates who blame the Colonel and his friends for the expulsion of their friend, Paul. There is much tension between Pudge's friends and the Weekday Warriors because of Paul's expulsion. Takumi claims that they are innocent because their friend Marya was also expelled during the incident. However, Alaska later admits that she told on Marya and Paul to the dean, Mr. Starnes, to save herself from being punished.

The gang celebrates a series of pranks by drinking and partying, and an inebriated Alaska confides about her mother's death from an aneurysm when she was eight years old. Although she didn't understand at the time, she feels guilty for not calling 911. Pudge figures that her mother's death made Alaska impulsive and rash. He concludes that the labyrinth was a person's suffering and that humans must try to find their way out. Afterwards, Pudge grows closer to Lara, and they start dating. A week later, after another 'celebration', an intoxicated Alaska and Pudge spend the night in each other's presence, when suddenly Alaska receives a phone call which causes her to go into hysterics. Insisting that she has to leave, Alaska drives away while drunk with Pudge and the Colonel distracting Mr. Starnes. They later learn that Alaska has crashed her car and died.

The Colonel and Pudge are devastated and blame themselves, wondering about her reasons for undertaking the urgent drive and even contemplating that she might have deliberately killed herself. The Colonel insists on questioning Jake, her boyfriend, but Pudge refuses, fearing that he might learn that Alaska never loved him. They argue and the Colonel accuses Pudge of only loving an idealized Alaska that Pudge made up in his head. Pudge realizes the truth of this and reconciles with the Colonel.

As a way of celebrating Alaska's life, Pudge, the Colonel, Takumi, and Lara team up with the Weekday Warriors to hire a male stripper to speak at Culver's Speaker Day. The whole school finds it hilarious; Mr. Starnes even acknowledges how clever it was. Pudge finds Alaska's copy of The General in His Labyrinth with the labyrinth quote underlined and notices the words "straight and fast" written in the margins. He remembers Alaska died on the morning after the anniversary of her mother's death and concludes that Alaska felt guilty for not visiting her mother's grave and, in her rush, might have been trying to reach the cemetery. On the last day of school, Takumi confesses in a note that he was the last person to see Alaska, and he let her go as well. Pudge realizes that letting her go doesn't matter as much anymore. He forgives Alaska for dying, as he knows Alaska would forgive him for letting her go.

Characters

- Miles Halter

- Miles "Pudge" Halter is nicknamed because he is tall and skinny. He is the novel's main character, who has an unusual interest in learning famous people's last words. He transfers to the boarding school Culver Creek in search of his own "Great Perhaps". Pudge is attracted to Alaska Young, who for most of the novel has a mixed relationship, mostly not returning his feelings.

- Alaska Young

- Alaska is the wild, unpredictable, beautiful, and enigmatic girl with a sad backstory who captures Miles' attention and heart. She acts as a confidante to her friends, frequently assisting them in personal matters, including providing them with cigarettes and alcohol. She is described as living in a "reckless world." The second half of the novel focuses around the car accident that took her life and the other characters coping with not knowing if it was an accident or a suicide.

- Chip Martin

- Chip "The Colonel" Martin is five feet tall but "built like a scale model of Adonis",[14] he is Alaska's best friend and Miles' roommate. He is the strategic mastermind behind the schemes that Alaska concocts, and in charge of everyone's nicknames. Coming from a poor background, he is obsessed with loyalty and honor, especially towards his beloved mother, Dolores, who lives in a trailer.

- Takumi Hikohito

- Takumi is a gifted Japanese emcee/hip-hop enthusiast and friend of Alaska and Chip. He often feels overlooked in the plans of Miles, Chip, and Alaska. Towards the end of the novel he returns to Japan.

- Lara Buterskaya

- Lara is a Romanian immigrant, she is Alaska's friend and becomes Miles' girlfriend and, eventually, ex-girlfriend. She is described as having a light accent.

- Mr. Starnes

- Mr. Starnes is the stern Dean of Students at Culver Creek, nicknamed "The Eagle" by the students. He is pranked by Miles, Chip, Alaska, Lara and Takumi multiple times throughout the novel.

Themes

Search for meaning

After Alaska's death, Pudge and Colonel investigate the circumstances surrounding the traumatic event. While looking for answers, the boys are subconsciously dealing with their grief, and their obsession over these answers transforms into a search for meaning. Pudge and Colonel want to find out the answers to certain questions surrounding Alaska's death, but in reality, they are enduring their own labyrinths of suffering, a concept central to the novel. When their theology teacher Mr. Hyde poses a question to his class about the meaning of life, Pudge takes this opportunity to write about it as a labyrinth of suffering. He accepts that it exists and admits that even though the tragic loss of Alaska created his own labyrinth of suffering, he continues to have faith in the "Great Perhaps,'" meaning that Pudge must search for meaning in his life through inevitable grief and suffering. Literary scholar Barb Dean analyzes Pudge and the Colonel's quest for answers as they venture into finding deeper meaning in life. Because this investigation turns into something that is used to deal with the harsh reality of losing Alaska, it leads to Pudge finding his way through his own personal labyrinth of suffering and finding deeper meaning to his life.[15]

Grief

When Alaska dies unexpectedly, the repercussions in the lives of her friends are significant, especially for Pudge and the Colonel. Scholar Barb Dean concludes that it is normal to seek answers about what happened and why. She also points out that in writing Looking for Alaska, John Green wished to dive deeper into the grieving process by asking the question "how does one rationalize the harshness and messiness of life when one has, through stupid, thoughtless, and very human actions, contributed to that very harshness?" [16] Pudge and the Colonel blame themselves for Alaska's death because they do not stop her from driving while intoxicated. Because of this, their grieving process consists of seeking answers surrounding her death since they feel that they are responsible. Ultimately, Miles is able to come to the conclusion that Alaska would forgive him for any fault of his in her death and thus his grief is resolved in a healthy way.[17]

Coming of Age

Throughout the book, the events that Miles and other characters experience are typical coming-of-age situations. By the end of the book, it is clear that Miles has grown throughout the year. Book reviews often note this theme, bringing up the instances in the book such as grief that cause the characters to look at life from a new and more mature perspective.[18] Scholar Barb Dean also concludes that the characters grow up faster than expected while investigating Alaska's death because exploring the concept of the labyrinth of suffering is Miles' "rite of passage" into adulthood, and he learns more about himself through grieving for Alaska.[15] Reviews also note activities such as drinking and smoking, which, though controversial, are often viewed as rites of passage by the teenagers in this novel.[19]

Hope

The theme of hope plays a major role in Looking for Alaska. Even though some of the novel's prominent themes are about death, grief and loss, John Green ties hope into the end of the novel to solve Pudge's internal conflict brought on by Alaska's death. In Barb Dean's chapter about the novel, she takes a closer look into Mr. Hyde's theology class where he discusses the similarity of the idea of hope between the founding figures of Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism. Mr. Hyde also asks the class what their call for hope is, and Pudge decides his is his escape of his personal labyrinth of suffering. For Pudge, his call for hope is understanding the reality of suffering while also acknowledging that things like friendship and forgiveness can help diminish this suffering. Dean notes that Green has said that he writes fiction in order to "'keep that fragile strand of radical hope [alive], to build a fire in the darkness.'" [20]

Reception

Reviews of Looking for Alaska are generally positive. Many comment on the relatable high school characters and situations as well as more complex ideas such as how topics like grief are handled. Overall, many reviewers agree that this is a coming of age story that is appealing to both older and younger readers.[21][19] There has been much controversy surrounding this novel, however, especially in school settings. Parents and school administrators have questioned the novel's language, sexual content, and depiction of tobacco and alcohol use.[22] Looking for Alaska has been featured on the American Library Association's list of Frequently Challenged Books in 2008, 2012, 2013, 2015, and 2016.[23] The novel was awarded the Michael L. Printz award in 2006 and has also won praise from organizations such as the American Library Association, School Library Journal, and the Los Angeles Times among others.[24]

Controversy

Marion County, Kentucky

In 2016 in Marion County, Kentucky, parents have urged schools to drop it from the curriculum, referring to it as influencing students "to experiment with pornography, sex, drugs, alcohol and profanity."[25] Although the teacher offered an opt-out book for the class, one parent still felt as though the book should be banned entirely and filed a formal complaint. After the challenge, students were given an alternate book for any parents who were not comfortable with their children reading the book. One parent still insisted on getting the book banned and filed a Request for Reconsideration on the basis that Looking For Alaska would tempt students to experiment with drugs, alcohol, and sex despite the decisions made after the challenge.[26]

Depew High School, Buffalo New York

Two teachers at Depew High School near Buffalo, New York, used the book for eleventh grade instruction in 2008. Looking For Alaska was challenged by parents for its sexual content and moral disagreements with the novel. Despite the teachers providing an alternate book, parents still argued for it to be removed from curriculum due to its inappropriate content such as offensive language, sexually explicit content, including a scene described as "pornographic", and references to homosexuality, drugs, alcohol, and smoking. The book was ultimately kept in the curriculum by the school board after a unanimous school board vote with the stipulation that the teachers of the 11th grade class give the parents a decision to have their children read an alternate book. Looking for Alaska was defended by the school district because they felt it dealt with themes relevant to students of this age, such as death, drinking and driving, and peer pressure.[27]

Knox and Sumner Counties, Tennessee

In March 2012, The Knoxville Journal reported that a parent of a 15-year-old Karns High School student objected to the book's placement on the Honors and Advanced Placement classes' required reading lists for Knox County high schools on the grounds that its sex scene and its use of profanity rendered it pornography.[28] Ultimately, students were kept from reading the novel as a whole, but Looking For Alaska was still available in libraries within the district. In May 2012, Sumner County in Tennessee also banned the teaching of Looking For Alaska. The school's spokesman argued that two pages of the novel included enough explicit content to ban the novel.

Controversy Due to Cover Design

Further controversy came from the cover art. In August 2012, Green acknowledged that the extinguished candle on the cover leads to "an improbable amount of smoke", and explained that the initial cover design did not feature the candle. Green said that certain book chains were uncomfortable with displaying or selling a book with a cover that featured cigarette smoke, so the candle was added beneath the smoke.[29] In John Green's box set, released on October 25, 2012, the candle has been removed from the cover. Further paperback releases of the book also have the candle removed.

Author's Response to Controversy

Green defended his book in his vlog, Vlogbrothers. The video, entitled "I Am Not A Pornographer", describes the Depew High School challenge of Looking For Alaska and his anger at the description of his novel as pornography. Green defends the inclusion of the oral sex scene in Looking for Alaska stating, "The whole reason that scene in question exists in Looking for Alaska is because I wanted to draw a contrast between that scene, when there is a lot of physical intimacy, but it is ultimately very emotionally empty, and the scene that immediately follows it, when there is not a serious physical interaction, but there's this intense emotional connection." Green argues that the misunderstanding of his book is the reason for its controversy, and calls to people to understand the actual literary content before judging specific scenes. He also condemns the way that groups of parents underestimate the intelligence of teenagers and their ability to analyze literature. He ends with encouraging his viewers to attend the Depew School Board hearing to defend the choice of parents, students, and teachers to have Looking for Alaska included in public schools.[30]

Adaptation

The film rights to the novel were acquired by Paramount Pictures in 2005. The screenplay was potentially going to be written and directed by Josh Schwartz (creator of The O.C.)[31] but, due to a lack of interest by Paramount, the production had been shelved indefinitely.[32] It had been reported that Paramount was putting the screenplay in review due to the success of the film adaptation of Green's breakout novel, The Fault in Our Stars. On February 27, 2015, The Hollywood Reporter announced that Scott Neustadter and Michael H. Weber, screenwriters for Temple Hill Entertainment who had worked on adaptations for The Fault in Our Stars and Paper Towns, would be writing and executive producing for the film.[33] Paramount was actively casting the latest version of the screenplay, which was written by Sarah Polley.[34][35] Rebecca Thomas was set to direct.[36] Green also confirmed that Neustadter and Weber were still involved with the film.[37] In August 2015, it was announced filming would begin in the fall in Michigan.[38] It was later announced that filming would begin in early 2016 because of lack of casting decisions. Later in 2016, John Green announced in a Vlogbrother's video and on social media that the film adaption has once again been shelved indefinitely.[39] John Green explained, "It has always fallen apart of one reason or another."[40]

On May 9, 2018 it was announced that Hulu would be adapting the novel into an 8-episode limited series.[41]

Footnotes

- Bob Carlton (2005-03-13). "One-time Indian Springs student finds his way in first novel".

References

- ↑ American Library Association (2010). "Michael L. Printz Winners and Honor Books". Archived from the original on 2011-02-17. Retrieved 2011-02-03.

- ↑ Kathy Rosa, ed. (2016-04-01), The State of America's Libraries, 2016 (PDF), retrieved 2016-06-07

- 1 2 vlogbrothers (2010-08-06), Looking for Alaska at My High School, retrieved 2017-10-27

- ↑ vlogbrothers (2015-02-24), Who I Was in High School, retrieved 2017-10-27

- ↑ Mendelsohn, Aline (2005-02-21). "From Last Words to First Book". The Orlando Sentinel.

- ↑ Green, John. "Questions about Looking for Alaska (SPOILERS!): Questions about Writing and Inspiration". Archived from the original on 2011-12-05.

- ↑ John Green's Legendary High School Prank. YouTube. 8 December 2007. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ "Children's Paperback Books". Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/best-sellers-books/2016-05-08/young-adult-paperback/list.html

- ↑ "Children's Paperback Books - Best Sellers - The New York Times". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ↑ Diaz, Ellie. "Spotlight on Censorship: "Looking For Alaska"". Journal of Intellectual Freedom Blog. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ↑ Green, John (28 December 2006). Looking for Alaska. Penguin Young Readers Group. p. 14. ISBN 9780142402511.

- ↑ Green, John (28 December 2006). Looking for Alaska. Penguin Young Readers Group. p. 25. ISBN 9780142402511.

- ↑ Green, John (28 December 2006). Looking for Alaska. p. 18. ISBN 9780142402511.

- 1 2 Dean, Barb (2010). "The Power of Young Adult Literature to Nourish the Spirit: An Examination of John Green's Looking for Alaska". Literature and Belief. 30 (2): 31.

- ↑ Dean, Barb (2010). "The Power of Young Adult Literature to Nourish the Spirit: An Examination of John Green's Looking for Alaska". Literature and Belief. 30 (2): 29.

- ↑ Green, John (2005). Looking for Alaska. Dutton Juvenile. p. 221. ISBN 0-525-47506-0.

- ↑ Barkdoll, Jayme K., and Lisa Scherff. ""Literature is Not a Cold, Dead Place": An Interview with John Green." English Journal 97.3 (2008): 67-71. ProQuest Central, Research Library. Web.

- 1 2 Ritchie, John. "Looking for Alaska." ALAN Review 32.3 (2005): 36. ProQuest Central. Web.

- ↑ Dean, Barb (2010). "The Power of Young Adult Literature to Nourish the Spirit: An Examination of John Green's Looking for Alaska". Literature and Belief. 30 (2): 32–33.

- ↑ Gallo, Don. "The very Best Possibilities, Part Two." English Journal 95.5 (2006): 107-10. ProQuest Central, Research Library. Web.

- ↑ "Spotlight on Censorship: 'Looking for Alaska' - Intellectual Freedom Blog". Intellectual Freedom Blog. 2017-04-13. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ admin (2013-03-26). "Frequently Challenged Books". Advocacy, Legislation & Issues. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ↑ "Awards". lookingforalaska10.com. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ Flood, Alison (2016-04-28). "US battle over banning Looking for Alaska continues in Kentucky". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- ↑ [infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/15CBB52D43D0E208?p=AWNB "The heart of education - Students need opportunities to think through situations for themselves"] Check

|url=value (help). Lebanon Enterprise (KY). NewsBank. Retrieved 6 December 2017. - ↑ Winchester, Laura E. "Committee will review controversial teenage book - Board will then decide if novel can be textbook". The Buffalo news. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ↑ Flood, Alison (28 April 2016). "US battle over banning Looking for Alaska continues in Kentucky". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ↑ In Which the Candle Dies. YouTube. 28 August 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ Green, John. "I Am Not A Pornographer". Youtube. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ↑ "Interview with Josh Schwartz". Summer 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ↑ "John Green New York Times Bestselling Author - Movie Questions". Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ↑ "Fault in Our Stars Writers, Producers Reuniting for Next John Green Adaptation (Exclusive)". Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ↑ "Sarah Polley will adapt and direct John Green's Looking for Alaska". Entertainment Weekly's EW.com. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ "Breakdown Express". talentrep.breakdownexpress.com. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ↑ "Rebecca Thomas to direct adaptation of John Green's Looking for Alaska". Entertainment Weekly. 24 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ↑ vlogbrothers (2015-06-30), "Some News", Youtube, retrieved 2016-01-22

- ↑ Christine (August 8, 2015). "John Green's Looking for Alaska will film in Michigan this fall". On Location Vacations. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ↑ John Green Looking for Alaska Movie Doomed

- ↑ vlogbrothers (2016-01-19), The Looking for Alaska Movie, Davos, and Hufflepuff Shade: It's Question Tuesday, retrieved 2017-11-10

- ↑ Andreeva, Nellie (2018-05-10). "Hulu Ordering 'Looking For Alaska' Limited Series From Josh Schwartz Based On John Green's Novel From Paramount TV". Deadline. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

Bibliography

- Green, John (28 December 2006). Looking for Alaska. Penguin Young Readers Group. ISBN 9780142402511.

External links

- Looking For Alaska is on the ALA 2005 Teens' Top Ten