Long Bridge (Potomac River)

| Long Bridge | |

|---|---|

The Long Bridge in 1861 seen from the Virginia shore | |

| Coordinates | 38°52′29″N 77°02′18″W / 38.87477°N 77.03847°WCoordinates: 38°52′29″N 77°02′18″W / 38.87477°N 77.03847°W |

| Carries |

1809-1904: Pedestrians, horses, vehicles, railroad, streetcars 1904-Present: Railroad only (Amtrak/VRE/CSX) |

| Crosses | Potomac River |

| Locale | Washington, D.C. |

| Characteristics | |

| Material |

1809-1904: Timber 1904-Present: Steel and timber |

| Rail characteristics | |

| No. of tracks | 2 |

| History | |

| Opened | 1809 |

| Rebuilt | 1863, 1884 and 1904 |

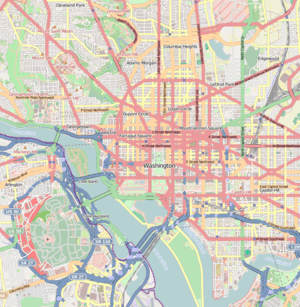

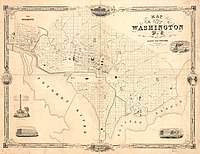

Long Bridge Location in Washington, D.C. | |

Long Bridge connects Washington, D.C. to Arlington, Virginia over the Potomac River. It was originally built in 1808, repaired and replaced several times in the 19th Century. It originally was used for foot, horse and stagecoach traffic. The current bridge was build in 1904 using ten recycled truss spans from the old Delaware River bridge in Trenton, one new truss span and a swing draw. It is used only for railroad traffic.

History

Original bridge

The building of the Long Bridge by The Washington Bridge Company was authorized on February 5, 1808 by an Act of Congress.[1] President Thomas Jefferson signed it into law soon after. It was named after its size and not after a person. It was built to provide foot, horse and stagecoach traffic an access route to Washington City.[2]

Built as a timber pile structure with two draw spans, it connected the District of Columbia to Virginia. On the District side, it landed at the end of Maryland Avenue SW where 14th Street SW. Prior to being built, only a ferryboat connected Alexandria, VA to the Capital. This could be a treacherous crossing when the river froze as the river was very wide.[2]

A board of commissioners would oversee the subscription of stocks to raise capital for the build, not to exceed $200,000. It was to be built between Maryland Avenue and Alexander's island, be at least 36 feet wide, able to withstand foot, horses, cattle and carriages. A secure railing was to be in place on both sides of the bridge and be at least 4 feet high. A 6-foot wide section on one side was to be reserved for pedestrians and also be separated from the rest of the traffic with a 4-foot high railing.[1]

Over the main channel, a 35-foot draw was to remain open to allow boats to pass through. Each draw leaf was to be 20 feet wide (instead of the 36 feet for the rest of the bridge). The bridge was stock at all times twenty good lamps with enough oil for them. Four lamps were to remain on all night at the draw, while the others were to remain on until midnight. Over the Maryland Channel, a draw at least 15 feet wide is to also be in place with the same restriction as for the other one.[1]

A toll was put in place with prices set by Congress and posted at the bridge for up to 60 years after opening:

- Foot passenger: 6 1/4 cents

- Person and horse: 18 3/4 cents

- Chaise, sulky or riding chair: 37 1/2 cents

- Coach, coachee, stage-wagon, chariot, phaeton or curricle or other riding carriage: 100 cents with an additional 12 1/2 cents for each horse or other animal (more than two) pulling the carriage

- Four-wheeled cart, dray or other two-wheeled carriage of burthen: 18 3/4 cents with an additional 12 1/2 cents for each horse or other animal (more than one) pulling the cart

- Sheep or swine: 3 cents each (Only one person per team or drove passes for free)

- Horse or neat cattle not pulling a coach or cart or with a rider: 6 1/4 cents (Only one person per team or drove passes for free)[1]

No toll is to be collected for vehicles and passengers:

- with property of the United States

- Troops of the United States, Militia, state or District of Columbia marching in a body, any cannon or equipment belonging to the United States[1]

The bridge opened to traffic on May 20, 1809. On August 25, 1814, after the Battle of Bladensburg the previous day, the British troops burned the north end of the bridge as they entered Washington City. The American troops had retreated to Virginia and burnt the south end of the bridge. It was restored to service in 1816 after the end of the War of 1812.[2]

Purchase by the United States

It was damaged on February 22, 1831, when high water and ice carried away several spans of the bridge.[3] The following year, Congress purchased the bridge for $20,000 and appropriated $60,000 to repair it. However, more fund would be needed to complete the project.[2]

On October 30, 1835, the bridge was reopened with President Andrew Jackson and his Cabinet present. It was to remain in its current state until the mid-1850s. On September 7, 1846, President James K. Polk retroceded Alexandria to the State of Virginia on fears that slavery would be abolished in the Capital.[2]

Since 1835, the B&O Railroad had been provided access to Washington City through the Northeast quadrant. There were several attempts to bring the railroad to Alexandria City.[2] The A&W Railroad connected the B&O Railroad New Jersey Avenue Station located on Capitol Hill to the Long Bridge on the north shore by 1855 and in Alexandria by the end of 1857. However, the Virginia legislature had banned any other connections and tracks were not placed on the bridge. Goods were offloaded, transported over the bridge in omnibuses over the bridge and reloaded on the other side.[2]'

Civil War

In spite of several requests, from the President of the B&O company for permission to built a sturdier span or replace the current structure with Congress, nothing was approved.[4] With the beginning of the civil War in 1861, and the secession of the state of Virginia on May 23, 1861, the value of the bridge was made evident. 13,000 Union Troops moved in to take control of the bridge along with Alexandria and its railroad on May 25, 1861. Under the command of Colonel John G. Barnard, Fort Jackson (Virginia) is built to guard the bridge to avoid the passage of spies and invasion by the Confederates with four cannons present in the fort.[2][5]

On 11 February 1862, Daniel McCallum was appointed Military Director and Superintendent of the Union railroads, with the staff rank of colonel, by Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War. McCallum had authority to "enter upon, take possession of, hold and use all railroads, engines, cars, locomotives, and equipment that may be required for the transport of troops, arms, ammunition, and military supplies of the United States, and to do and perform all acts... that may be necessary and proper... for the safe and speedy transport aforesaid," he wrote in a 1866 report.[6]

Rails were placed on the bridge that was now several decades old. It quickly became obvious, the structure would not be able to withstand heavy loads. Lightly loaded railroad cars were transshipped over the bridge and pulled by horses. Finally, in 1863, a new strong structure is built that can carry the newer and heavier locomotives and wagons. It was built about 100 feet down river and had two draw spans. Both structures were used during the Civil War under the control of the Union Army.[2][7]

The bridge provided access to the city including for wounded Union Soldiers heading for the hospitals set up all over the city. The closest one was Armory Square Hospital located only a few blocks from the bridge.

General Daniel McCallum (with the beard) on the Long Bridge looking toward Alexandria, VA

General Daniel McCallum (with the beard) on the Long Bridge looking toward Alexandria, VA Long Bridge in 1863 looking toward Washington, DC

Long Bridge in 1863 looking toward Washington, DC Long Bridge around 1865 looking toward Washington, DC

Long Bridge around 1865 looking toward Washington, DC Long Bridge looking toward Washington, DC probably in 1862 (no rails on the new span)

Long Bridge looking toward Washington, DC probably in 1862 (no rails on the new span) The old span (left) and the new (right) Long Bridge after 1863 looking toward Washington, DC

The old span (left) and the new (right) Long Bridge after 1863 looking toward Washington, DC The new span after 1863

The new span after 1863 Union troops guarding a bridge over the Potomac River to Virginia

Union troops guarding a bridge over the Potomac River to Virginia

Post Civil War

With the end of the war in 1865, the bridge is handed over back to B&O by the Union Army. While the Civil War was over, a new war was only starting in the world of railroads in the District of Columbia, Maryland and Virginia. B&O had had a railroad monopoly in the District all this time. The competition came in the form of the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) (nicknamed the Pennsy). Local and Federal politics along with personal interests of politicians made it possible for the newcomer to gain access to the city. Pennsylvania Senator Simon Cameron, who happened to be a stockholder in the Northern Central Railroad (owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad) became Secretary of War from 1861 to 1862, when he was removed from the position due to charges of payoffs and other irregularities helped the railroad gain control of the bridge. The Railroad was financing the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad (B&P) to get in the District. On June 21, 1870, Congress approves the B&P Railroad to use the Long Bridge in perpetuity free of cost. They are to keep the bridge in good repair and allow other railroads on the bridge.[2][8]

In Virginia, it also gained control of the Alexandria & Fredericksburg Railroad and connected Alexandria to Richmond and Fredericksburg in 1872. A new Long Bridge is built with 18 fixed and 2 draw truss replacing the Civil War bridge. [9] In 1873, it is connected to the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station located on the National Mall at the corner of 6th Street NW and B Street NW (now Constitution Avenue).[2] On May 10, 1874, the B&O Railroad regains access to the Alexandria between Shepherds Point and Washington City, Virginia Midland & Great Southern Railroad at Alexandria using tugs and car floats.[10] On February 13, 1876, the B&O begins running cars via the (Potomac Junction between the Alexandria Branch and the B&P near Bennings Station[11]

On February 12, 1881, ice freshets damage the bridge by taking out three spans. It re-opens for traffic on February 19, 1881[12] In 1884, the bridge is rebuilt and strengthened in 1894.[13][14]

On June 30, 1891, the B&P Railroad grants the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway trackage rights over the bridge to its Washington station[15] On august 1, 1895, the B&P Railroad grants the use of the bridge to the Washington, Alexandria, and Mount Vernon Electric Railway (streetcars). Power cables are hung and the rent is set to $25,000 a year in the beginning.[16]

On February 19, 1898, the Washington Terminal Railway Company is incorporated in Virginia. It includes the PRR, RF&P, ACL, Southern Railway and C&O but not the B&O. It acquires the property of the Washington Southern Railway, the B&P Railroad terminals in Washington and Long Bridge.[17] Two years later, on July 31, 1900, a New Jersey holding company is formed between PRR, ACL, Southern Railway, C&O, Seaboard Air Line Railway and B&O to control the line between Richmond, VA and the Long Bridge.[18]

20th Century

In the early 20th Century, a general movement is sweeping the capital regarding railroads. The population wants at-grade railroad crossings eliminated and the Mall is seen as needing to be overhauled. This is accomplished by an act of Congress on February 12, 1901. It also calls for the replacement of the aging Long Bridge with a two-track rail bridge and a separate highway bridge.[19] This leads to the creation of the McMillan Plan of 1902 and Union Station completed in 1907.[20]

On August 25, 1904, a new double-track Long Bridge opens west of the old single track rail/road bridge of 1884 using ten recycled truss spans from the old Delaware River bridge in Trenton, one new truss span and a swing draw. The old Long Bridge remains in use for vehicles and trolley cars until the 14th Street road bridge is complete.[21] On January 11, 1906 the first streetcars use the 14th Street Bridge southbound, while the northbound cars remain on the old bridge. Both switch completely on February 12, when the bridge is officially opened and is known as the Highway Bridge. Vehicles continue to use the old bridge until December 15 when it is closed and abandoned two days later.[22]

21st Century

The 1904 Long Bridge has been exclusively used for the Railroad since its construction and is owned by CSX Transportation. It is used by CSXT freight trains, Amtrak and the Virginia Railway Express trains. Norfolk Southern Railway has tracking rights on the bridge but does not exercise those rights.[23]

In 2011, the District of Columbia Department of Transportation (DDOT) received a High Speed Intercity Passenger Tail grant from the Federal Railroad Administration for a two phase study in the feasibility of rehabilitating or replacing the Long Bridge.[23]

In 2016, the Long Bridge Project was started. The Federal Railroad Administration provided DDOT with a grant to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). After the publication of the draft, the public is being consulted for comments. The [24]

Phase I of the study was completed in winter 2015. Phase II started in the fall 2015 and completed in spring 2017 with public meetings on February 10, 2016 and September 14, 2016. The project is now in Phase III (Spring 2017 to Fall 2020). A public meeting took place on December 14, 2017 with another meeting to happen in the fall 2018.[25][26][27]

While the project is focused on the Railway traffic of the bridge, it is considering the cycling and pedestrian options to connect the District of Columbia to Arlington, Virginia.[28]

The through-truss swing span of the 1904 Long Bridge in 2010

The through-truss swing span of the 1904 Long Bridge in 2010.jpg) The 1904 Long Bridge in 2013

The 1904 Long Bridge in 2013

Legacy

Today, a Public park is named after the Long Bridge and stands close to the original landing near Crystal City, Arlington, Virginia anda short distance from the Pentagon. Long Bridge Park is managed by Arlington County and covers over 30 acres with sports fields, walkways and playgrounds for children. It is accessible via Long Bridge Drive located between Interstate 395 and the George Washington Memorial Parkway.[29]

See Also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 An Act authorizing the erection of a bridge over the river Potomac within the District of Columbia - 10th Congress Session I - Chapter 15 - 1808.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 National Railway Historical Society - Washington DC Chapter - History of the Long Railroad Bridge Crossing Across the Potomac River by Robert Cohen - http://www.dcnrhs.org/learn/washington-d-c-railroad-history/history-of-the-long-bridge

- ↑ Additional damage occurred due to high water and/or ice in 1836, 1841, 1856, 1860, 1863, 1866 and 1887

- ↑ Extension of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad across the Long Bridge - The Evening Star - Tuesday, May 22, 1860

- ↑ Cooling III, Benjamin Franklin; Owen II, Walton H. (2010). Touring the Forts South of the Potomac: Fort Runyan and Fort Jackson. Mr. Lincoln's Forts: A Guide to the Civil War Defenses of Washington (New ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-8108-6307-1. LCCN 2009018392. OCLC 665840182. Retrieved 2018-03-07 – via Google Books.

- ↑ David A. Pfeiffer "Working Magic with Cornstalks and Beanpoles: Records Relating to the U.S. Military Railroads during the Civil WarSummer" in: Prologue 2011, Vol. 43, No. 2.

- ↑ Norfolk Southern Railway History, "Orange and Alexandria Railroad" Piedmont Railroaders, Spring 2002. Accessed June 19, 2008.

- ↑ 41st Congress - Session II - Chapter 142 - June 21, 1870 An Act supplementary to an Act entitled "An Act to authorize the Construction, Extension [Extension, Construction] and Use of a lateral Branch of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Company into and within the District of Columbia," approved February five, eighteen hundred and seventy [sixty-seven]

- ↑ The Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society - 1872 - http://www.prrths.com/newprr_files/Hagley/PRR1872.pdf

- ↑ http://www.prrths.com/newprr_files/Hagley/PRR1874%20Mar%2005.pdf PRR Chronology: Mar. 10, 1874

- ↑ http://www.prrths.com/newprr_files/Hagley/PRR1876%20April%2006.pdf PRR Chronology: Feb. 13, 1876

- ↑ http://www.prrths.com/newprr_files/Hagley/PRR1881.pdf PRR Chronology: 1881

- ↑ http://www.prrths.com/newprr_files/Hagley/PRR1884.pdf PRR Chronology: 1884

- ↑ http://www.prrths.com/newprr_files/Hagley/PRR1894.pdf PRR Chronology: 1884

- ↑ http://www.prrths.com/newprr_files/Hagley/PRR1891.pdf PRR Chronology: 1891

- ↑ http://www.prrths.com/newprr_files/Hagley/PRR1895.pdf PRR Chronology: 1895

- ↑ http://www.prrths.com/newprr_files/Hagley/PRR1898.pdf PRR Chronology: 1898

- ↑ http://www.prrths.com/newprr_files/Hagley/PRR1900.pdf PRR Chronology: 1900

- ↑ 56th Congress - Session II - Chapter 354 - February 12, 1901

- ↑ http://www.prrths.com/newprr_files/Hagley/PRR1901.pdf PRR Chronology: 1904

- ↑ http://www.prrths.com/newprr_files/Hagley/PRR1904.pdf PRR Chronology: 1904

- ↑ http://www.prrths.com/newprr_files/Hagley/PRR1906.pdf PRR Chronology: 1906

- 1 2 The Long Bridge Project - Notice of Intent No. 166 http://longbridgeproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/noi916.pdf

- ↑ The Long Bridge Project - Description - http://longbridgeproject.com/project-description/

- ↑ The Long Bridge Project - Project Schedule - http://longbridgeproject.com/project-schedule/

- ↑ The Long Bridge Project - Past Meetings - http://longbridgeproject.com/past-meetings/

- ↑ The Long Bridge Project - Upcoming Meetings - http://longbridgeproject.com/upcoming-meetings/

- ↑ The Long Bridge Project - http://longbridgeproject.com/

- ↑ Arlington County Website - Long Bridge Park