Lesser bilby

| Lesser bilby | |

|---|---|

| |

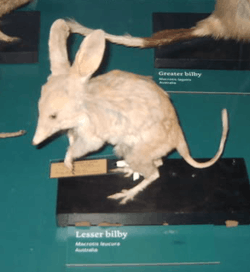

| A stuffed lesser bilby specimen at Tring Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Peramelemorphia |

| Family: | Thylacomyidae |

| Genus: | Macrotis |

| Species: | M. leucura |

| Binomial name | |

| Macrotis leucura Thomas, 1887 | |

| |

| Historic lesser bilby range in orange | |

The lesser bilby (Macrotis leucura), also known as the yallara, the lesser rabbit-eared bandicoot or the white-tailed rabbit-eared bandicoot, was a rabbit-like marsupial. The species was first described by Oldfield Thomas as Peregale leucura in 1887 from a single specimen from a collection of mammals of the British Museum.[2] Reaching the size of a young rabbit, this species lived in the deserts of Central Australia. Since the 1950s–1960s, it has been believed to be extinct.

Description

The lesser bilby was a medium-sized marsupial with a body mass of 300 to 450 grams (11 to 16 oz).[3] Its fur colour ranged from pale yellowish-brown to grey-brown with pale white or yellowish-white fur on its belly, with white limbs and tail.[3][4] The tail of this animal was long, about 70% of its total head-body length.

Distribution and habitat

Very little is known about its former range and distribution, as the species was collected only six times in modern history, with the first of these coming from an unknown region.[5]

In modern times this species was endemic to the Gibson and Great Sandy deserts of arid central Australia and to northeast South Australia and adjoining southeast Northern Territory in the northern half of the Lake Eyre Basin.[3]

It preferred to live in sandy and loamy deserts, sandplains and dunes covered with spinifex, mulga, zygochloa canegrass and/or tussock grass,[3] as well as in triodia hummock grassland with sparse low trees and shrubs.[6]

Ecology and behaviour

The lesser bilby, like its surviving relatives, was a strictly nocturnal animal. It was an omnivore feeding on ants, termites, roots,[3] seeds,[7] but it also hunted and fed on introduced rodents.

It burrowed in sand dunes, constructing burrows 2–3 metres (6 ft 7 in–9 ft 10 in) deep and closing the entrance with loose sand by day. It is suggested that it may have bred non-seasonally[8] and that giving birth to twins was normal for this species.[7]

Unlike its living relative the greater bilby, the lesser bilby was described as aggressive and tenacious. Finlayson wrote that this animal was "fierce and intractable, and repulsed the most tactful attempts to handle them by repeated savage snapping bites and harsh hissing sounds".

Extinction

Since its discovery in 1887, the species was rarely seen or collected and remained relatively unknown to science. In 1931, Finlayson encountered many of them near Cooncherie Station, collecting 12 live specimens.[9] Although according to Finlayson this animal was abundant in that area,[7] these were the last lesser bilbies to be collected alive.

The last specimen ever found was a skull picked up below a wedge-tailed eagle's nest in 1967 at Steele Gap in the Simpson Desert, Northern Territory.[9] The bones were estimated as being under 15 years old.[10]

Indigenous Australian oral tradition suggests that this species may have possibly survived into the 1960s.[6]

The decline in numbers of the lesser bilby and ultimately its extinction was attributed to several different factors. The introductions of foreign predators like the domestic cat and fox, being hunted for food by native Australians,[4] competition with rabbits for food, changes in the fire regime and the degradation of habitat[6] have all been blamed for the extinction of this species. However, Jane Thornback and Martin Jenkins suggested in their book that the vegetation in the main part of its range remained intact, with little evidence of cattle or rabbit grazing and point to cats and foxes as the most likely cause of the extinction of the lesser bilby.[5]

References

- ↑ Burbidge, A.; Johnson, K. & Dickman, C. (2008). "Macrotis leucura". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 28 December 2008. Database entry includes justification for why this species is listed as extinct

- ↑ http://www.deh.gov.au/biodiversity/abrs/....me1b/25-ind.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-04. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- 1 2 Francis Harper (1945). Extinct and Vanishing Mammals of the Old World.

- 1 2 The IUCN Mammal Red Data Book. IUCN. 1982. p. 33. ISBN 978-2-88032-600-5.

- 1 2 3 http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/12651/0

- 1 2 3 Hedley Herbert Finlayson (1935). On mammals from the Lake Eyre Basin. Part 2. The Peramelidae.

- ↑ http://www.rainforestinfo.org.au/spp/Schouten/lesser_bilby.htm

- 1 2 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-05. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ↑ Tim Flannery & Peter Schouten (2001). A gap in nature.