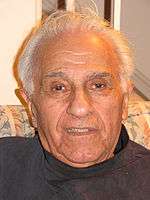

Leo Bretholz

| Leo Bretholz | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

March 6, 1921 Vienna, Austria |

| Died |

March 8, 2014 (aged 93) Pikesville, Maryland |

| Spouse(s) | Florine Cohen (m. 1952–2009; her death) |

| Children | Three |

Leo Bretholz (March 6, 1921 – March 8, 2014) was a Holocaust survivor who, in 1942, escaped from a train heading for Auschwitz.[1] He has also written a book on his experiences, titled Leap into Darkness.

He escaped seven times during the Holocaust.

Life

Leo Bretholz was born in Vienna, Austria, on March 6, 1921. His father, Max Bretholz, was a Polish immigrant who worked as a tailor and died in 1930. His Mother, Dora (Fischmann) Bretholz, also Polish, was born in 1891 and worked as a seamstress. He had two younger sisters, Henny and Edith (Ditta).[2]

After the Anschluss in March 1938, many of his relatives were arrested. At his mother’s insistence, he fled on a train to Trier, Germany, where he was met by a smuggler. He swam across the Sauer River into Luxembourg, where he spent five nights in a Franciscan monastery. He was arrested two days later in a coffee shop and chose to be taken to the Belgian border over arrest or being sent back to Germany. He arrived in Antwerp, Belgium, on November 11, 1938. He stayed in Antwerp for a peaceful eighteen months where he went to a public trade school to become an electrician as an alternative to being sent to an internment camp. He learned to speak Dutch. On May 9, 1940, he entered a hospital in Antwerp to have surgery on a hernia, but Antwerp was bombed the next morning before he could be operated on. Upon being discharged from the hospital, he was arrested as an enemy alien. Now that the war had reached Antwerp, he was an enemy to Belgium because he was an Austrian (now German) citizen. He was sent to St. Cyprien, an internment camp near the Spanish border. His friend Leon Osterreicher came to visit him and instructed him to escape by climbing under the camp’s fence. While living with distant relatives nearby, he was sent to an assigned residence in Cauterets, France, near the Pyrenees Mountains. He stayed at this residence for eight to ten months until on August 26, 1941, when the deportation began from this town. Upon a warning from the mayor of Luchon, he hid with his uncle overnight in the Pyrenees, returning the next day to find half of the ghetto’s population deported. He walked across the Swiss border with his cousin Albert Hershkowitz in October 1942, under the name Paul Meunier, only to be stopped by a Swiss Mountain Patrol and sent back to France. He was sent to the Rivesaltes internment camp where he remained for two weeks before being sent to Drancy, a large-scale deportation camp in the suburbs of Paris.[3]

On November 5, 1942, Bretholz was deported on convoy 42 with 1000 others headed for Auschwitz. With his friend Manfred Silberwasser he escaped through the window and leaped off the train.[1] Staying with two priests on subsequent nights, he and Manfred were given train tickets to Paris with a new set of false identification papers, this time under the name Marcel Dumont. Upon crossing into the Southern region (Vichy France), he was arrested again for abandoning his assigned residence. He spent nine months in prison, one month of which was in solitary confinement for having escaped for two days. He was released in September 1943. He was then sent to Septfonds forced labor camp for one month.

In October 1943 he was taken with thirteen other men to the Toulouse train station en route to the Atlantic coast to build fortifications. At this layover he spent hours to bend the bars, then climbed out of the train window and escaped into the city of Toulouse. In Toulouse his friend Manfred sent a third set of false papers, this time under the name Max Henri Lefevre. Bretholz joined the Jewish Resistance Group Compagnons De France, known as “La Sixieme” so he could travel freely throughout France. He was assigned to Limoges, a city in south-central France. On May 8, 1944, his hernia ruptured and he collapsed on a Limoges park bench and was sent by a passerby to a hospital, where he had surgery. He spent seventeen days in the hospital then returned for his dressings to be changed. He rejoined the underground movement and remained in Limoges until departing on a ship for New York on January 19, 1947.[3]

He moved in with his aunt and uncle in Baltimore, Maryland on January 29 and immediately sought work as a handyman. He worked in textiles, traveling around the Mid-Atlantic. He moved into his own apartment with his friend Freddie. He met his wife Florine Cohen Bretholz in November 1951, they married in July 1952. Bretholz had his first child, Myron, in 1955 and later had two daughters, named Denise and Edie. He received death notifications of his two sisters and mother in 1962, they had been deported to Auschwitz in April 1942, after which he had not heard from them. It was at this point he began to speak publicly about his experiences during the war.[3]

In 1968 he went into the retail book business. He lived in the Netherlands with his family for two years.[3] He co-wrote an autobiography, Leap into Darkness, with Michael Oleskar. He appeared in the documentary film Survivors Among Us.[4]

Until his death in 2014, he lived in Pikesville, Maryland, and was a regular speaker at a range of venues, including the annual Holocaust Remembrance Project, and a number of schools.

Fight for SNCF Reparations

Prior to his death, Leo Bretholz fought for reparations from SNCF, the French rail company that transported Jews to Nazi concentration and death camps. When the class action lawsuit refused to be heard by the Supreme Court, the lower court ruling that the case was outside US jurisdiction stood and the case died. When his home state of Maryland proposed a high speed rail line, he testified in the state legislature against permitting SNCF to bid on the project.[5]

Bibliography

- Bretholz, Leo; Olesker, Michael (1998). Leap into Darkness: Seven Years on the Run in Wartime Europe. Baltimore, MD: Woodholme House Publishers. ISBN 0385497059.

References

- 1 2 Shaver, Katherine (March 9, 2014). "Opposition to Maryland rail line bidder raises questions about accountability for Holocaust". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ↑ Vitello, Paul (2014-03-29). "Leo Bretholz, 93, Dies; Escaped Train to Auschwitz". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-02-12.

- 1 2 3 4 Michael, Olesker, (1999-01-01). Leap into darkness seven years on the run in wartime Europe. Anchor Books. ISBN 0385497059. OCLC 722971331.

- ↑ Weiner, Deborah; Bretholz, Leo; WBAL-TV (Television station : Baltimore, Md.); Hearst-Argyle Television, Inc (2005-01-01), Survivors among us, WBAL-TV, retrieved 2017-02-12

- ↑ Vitello, Paul (2014-03-29). "Leo Bretholz, 93, Dies; Escaped Train to Auschwitz". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-02-12.

External links

- Jewish Journal at the Wayback Machine (archived September 29, 2007)

- Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Hörspuren audio guide: Leo Bretholz talks about his childhood days in Vienna