Eastern red bat

| Eastern red bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Eastern red bat | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Vespertilionidae |

| Genus: | Lasiurus |

| Species: | L. borealis |

| Binomial name | |

| Lasiurus borealis Müller, 1776 | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

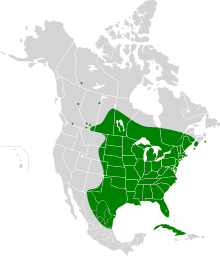

The eastern red bat (Lasiurus borealis) is a species of bat in the family Vespertilionidae. Eastern red bats are widespread across eastern North America, with additional records in Bermuda.

Taxonomy and etymology

It was described in 1776 by German zoologist Philipp Ludwig Statius Müller. He initially placed it in the genus Vespertilio, with the name Vespertilio borealis.[2] It was not placed into its current genus Lasiurus until the creation of the genus in 1831 by John Edward Gray.[3] Its species name "borealis" is Latin in origin, meaning "northern." Of the species in its genus, the eastern red bat is most closely related to other red bats, with which they form a monophyly. Its closest relatives are the Pfeiffer's red bat (Lasiurus pfeifferi), Seminole bat (L. seminolus), cinnamon red bat (L. varius), desert red bat (L. blossevillii), saline red bat (L. salinae), and the greater red bat (L. atratus).[4]

Description

The eastern red bat has distinctive fur, with its back brick red or rusty red and frosted with white. Individual hairs on its back are approximately 5.8 mm (0.23 in), while hairs on its uropatagium are 2.6 mm (0.10 in) long. Fur on its ventral surface is usually lighter in color, while the shoulders may appear white. Females are usually lighter in color than the males. Its entire body is densely furred, including its uropatagium. It is a medium-sized member of its genus, weighing 7–13 g (0.25–0.46 oz) and measuring 109 mm (4.3 in) from head to tail. Its ears are short and rounded, with triangular tragi. Its wings are long and pointed. Its tail is long, at 52.7 mm (2.07 in) long. Its forearm is approximately 40.6 mm (1.60 in) long. Its dental formula is 1.1.2.33.1.2.3, for a total of 32 teeth.[3]

Biology

The aspect ratio and wing loading of eastern red bat wings indicates that they fly relatively quickly and are moderately manueverable.[3] Eastern red bats are insectivorous, preying heavily on moths, with other insect taxa also consumed. They consume known pests, including gypsy moths, tent caterpillar moths, Cydia moths, Acrobasis moths, cutworm moths, and coneworm moths.[5]

Range and habitat

The eastern red bat is widely distributed in eastern North America and Bermuda.[6] It generally occurs east of the Continental Divide, including southern Canada and northeastern Mexico. In the winter, it occurs in the southeastern United States and northeastern Mexico, with greatest concentrations in coastal areas. In the spring and summer, it can be found in the Great Lakes region and the Great Plains region. Unlike the closely related hoary bat, males and females have the same geographic range throughout the year.[7] Formerly, some authors included the western United States, Central America, and the northern part of South America in its range,[3] but these populations have since been reassigned to the desert red bat, Lasiurus blossevillii.[6]

Conservation

The eastern red bat is evaluated as least concern by the IUCN, the lowest-priority conservation category. It meets the criteria for this designation because it has a wide geographic range, large population size, it occurs in protected areas, it tolerates some habitat disturbance, and its population size is unlikely to be declining rapidly.[1] Eastern red bats and other migratory tree bats are vulnerable to death by wind turbines via barotrauma.[8] The eastern red bat has the second-greatest mortality from wind turbines, with hoary bats most affected.[9] While it has been documented carrying the spores of Pseudogymnoascus destructans, the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome, no individuals have been observed with clinical symptoms of the disease.[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 Arroyo-Cabrales, J.; Miller, B.; Reid, F.; Cuarón, A.D.; de Grammont, P.C. (2016). "Lasiurus borealis". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T11347A22121017. Retrieved 2017-12-10.

- ↑ Müller, P.L.S. Des Ritters Carl von Linné vollständiges Natursystem: nach der zwölften lateinischen Ausgabe, und nach Anleitung des holländischen Houttuynischen Werks. 1. Gabriel Nicolaus Raspe. p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 Shump, K. A.; Shump, A. U. (1982). "Lasiurus borealis". Mammalian Species (183): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3503843.

- ↑ Baird, A. B.; Braun, J. K.; Mares, M. A.; Morales, J. C.; Patton, J. C.; Tran, C. Q.; Bickham, J. W. (2015). "Molecular systematic revision of tree bats (Lasiurini): doubling the native mammals of the Hawaiian Islands". Journal of Mammalogy. 96 (6): 1255–1274. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyv135.

- ↑ Clare, E. L.; Fraser, E. E.; Braid, H. E.; Fenton, M. B.; Hebert, P. D. (2009). "Species on the menu of a generalist predator, the eastern red bat (Lasiurus borealis): using a molecular approach to detect arthropod prey". Molecular ecology. 18 (11): 2532–2542. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04184.x.

- 1 2 Simmons, N. B. (2005). "Genus Lasiurus". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 458–459. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Cryan, P. M. (2003). "Seasonal distribution of migratory tree bats (Lasiurus and Lasionycteris) in North America". Journal of Mammalogy. 84 (2): 579–593. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2003)084<0579:SDOMTB>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Cryan, P. M.; Brown, A. C. (2007). "Migration of bats past a remote island offers clues toward the problem of bat fatalities at wind turbines". Biological Conservation. 139 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2007.05.019.

- ↑ Kunz, T. H.; Arnett, E. B.; Erickson, W. P.; Hoar, A. R.; Johnson, G. D.; Larkin, R. P.; Strickland, M. D.; Thresher, R. W.; Tuttle, M. D. (2007). "Ecological impacts of wind energy development on bats: questions, research needs, and hypotheses". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 5 (6): 315–324. doi:10.1890/1540-9295(2007)5[315:EIOWED]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ "Bats affected by WNS". White-Nose Syndrome.org. US Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lasiurus borealis. |