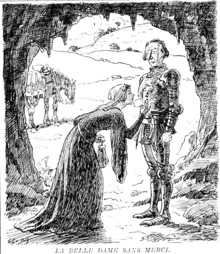

La Belle Dame sans Merci

.jpg)

"La Belle Dame sans Merci" ("The Beautiful Lady Without Mercy") is a ballad written by the English poet John Keats, who used the title of the 15th-century La Belle Dame sans Mercy by Alain Chartier, but nothing of the earlier poem's substance. The published 1820 version differs from Keats' own 1819 original.[1]

Considered an English classic, the poem is a good example of Keats' poetic preoccupation with love and death.[2] Despite its simplicity of structure, with only twelve stanzas of only four lines each in a simple ABCB rhyme scheme, the poem is nonetheless full of enigmas, and so resists simplicity of interpretation, of which there are many.

Poem

Of the two versions, scholars generally hold that the original is superior to the published version, for although the changes to the original are slight, they result in a loss of poetic power.

| The original version, 1819 | The published version, 1820 | |

|---|---|---|

|

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms, |

O what can ail thee, wretched wight, |

Analysis

"La Belle Dame sans Merci" is a popular form given an artistic by the Romantic poets. Keats uses a stanza of three iambic tetrameter lines with the fourth dimetric line which makes the stanza seem a self-contained unit, giving the ballad a deliberate and slow movement, and is pleasing to the ear. Keats uses a number of the stylistic characteristics of the ballad, such as the simplicity of the language, repetition, and absence of details; like some of the old ballads, it deals with the supernatural. Keats's economical manner of telling a story in "La Belle Dame sans Merci" is the direct opposite of his lavish manner in "The Eve of St. Agnes". Part of the fascination exerted by the poem comes from Keats' use of understatement.

Keats sets his simple story of love and death in a bleak wintry landscape that is appropriate to it: "The sedge has wither'd from the lake / And no birds sing!" The repetition of these two lines, with minor variations, as the concluding lines of the poem emphasizes the fate of the unfortunate knight and neatly encloses the poem in a frame by bringing it back to its beginning. Keats relates the condition of the trees and surroundings to the condition of the knight who is also broken.

In keeping with the ballad tradition, Keats does not identify his questioner, or the knight, or the destructively beautiful lady. What Keats does not include in his poem contributes as much to it in arousing the reader's imagination as what he puts into it. La belle dame sans merci, the beautiful lady without pity, is a femme fatale, a Circe-like figure who attracts lovers only to destroy them by her supernatural powers. She destroys because it is her nature to destroy. Keats could have found patterns for his "faery's child" in folk mythology, classical literature, Renaissance poetry, or the medieval ballad. With a few skillful touches, he creates a woman who is at once beautiful, erotically attractive, fascinating, and deadly.

Some readers see the poem as Keats' personal rebellion against the pains of love. In his letters and in some of his poems, he reveals that he did experience the pains, as well as the pleasures, of love and that he resented the pains, particularly the loss of freedom that came with falling in love.

In other media

Television

Californication - Season 1, Episode 5

Rosemary & Thyme - Season 1, Episode 1

Downton Abbey - Season 6, Episode 5

“Victoria” - Season 2, Episode 3

Visual depictions

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to La Belle Dame sans Merci. |

"La Belle Dame sans Merci" was a popular subject for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. It was depicted by Frank Dicksee, Frank Cadogan Cowper, John William Waterhouse, Arthur Hughes, Walter Crane, and Henry Maynell Rheam. It was also satirized in the December 1, 1920 edition of Punch magazine.

Musical settings

The best-known musical setting is that by Charles Villiers Stanford. It is a dramatic interpretation requiring a skilled (male) vocalist and equally skilled accompanist. It has remained popular and is included on many anthologies of English song or British Art Music recorded by famous artists. Patrick Hadley also wrote a version for tenor, four-part chorus, and orchestra.

A setting of the poem, in German translation, appears on the album Buch der Balladen by Faun.

A lyrical, mystical musical setting of this poem has been composed by Lorena McKennitt, published in her 2018 CD “Lost Souls”.

Film

The 1915 American film The Poet of the Peaks was based upon the poem. The main antagonist of the 2009 stop-motion animated dark fantasy film Coraline references the Belle Dame in the poem (see Books).

The stop-action animated fantasy film Coraline (2009, directed by Henry Selick) refers to the malevolent Other Mother as "beldam", and includes a similar theme of entrapment by a seemingly beautiful loving woman.

Books

The last two lines of the 11th verse are used as the title of a science fiction short story, "And I awoke and found me here on the cold hill's side", which is the Hugo and Nebula Award nominated short story by James Tiptree, Jr. (1973).

The last two lines of the first verse ("The sedge has withered from the lake/And no birds sing") were used as an epigraph for Rachel Carson's 1962 book Silent Spring, about the environmental damage caused by the irresponsible use of pesticides. The second line was repeated later in the book, as the title of a chapter about their specific effects on birds.

The line is also featured on page 27 of Philip Roth's The Human Stain in reaction to Coleman describing his new, far younger love interest.

The Beldam in Neil Gaiman's 2002 horror-fantasy novel Coraline references the mysterious woman who is also known as Belle Dame. Both share many similarities as both lure their protagonists into their lair by showing their love towards them and giving them treats to enjoy. The protagonists in both stories also encounter the ghosts who have previously met both women and warn the protagonist about their true colours and at the end of the story, the protagonist is stuck in their lair, with the exception of Coraline who managed to escape while the unnamed knight in this poem is still stuck in the mysterious woman's lair.

Vladimir Nabokov’s books, Lolita, Pale Fire and The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, allude to the poem.

In Hunting Ground by Patricia Briggs, La Belle Dame sans Merci is identified as The Lady of the Lake and is a hidden antagonist.

David Foster Wallace's 2011 novel The Pale King alludes to the poem in its title.

It is also mentioned in the story entitled "The case of Three Gables" from The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. In it Holmes compares and matches the character sketch of Isadora Klein with belle dame sans merci.

Cassandra Clare's 2016 collection of novellas Tales From the Shadowhunter Academy includes a novella titled Pale Kings and Princes, named after the line "I saw pale kings and princes too/Pale warriors, death-pale were they all". Three of the poem's stanzas are also excerpted in the story.

In an interview with The Quietus the English songwriter and musician John Lydon cited the poem as a favourite.[3]

L. A. Meyer's Bloody Jack series features a take on La Belle Dame sans Merci, adapted to reflect the protagonists age. Mary "Jacky" Faber became known as "La belle jeune fille sans merci".

Farley Mowat's 1980 memoir of his experiences in World War II is entitled And No Birds Sang.

Roger Zelazny’s Amber Chronicles refer to the poem in Chapter Five of The Courts of Chaos (1978) wherein the protagonist journeys to a land that resembles the poem.

John Kennedy Toole's novel A Confederacy of Dunces aludes to the poem in initially describing the main character's home.

In Chapter 32 of Kristine Smith's novel Law Of Survival the protagonist, Jani, reveals her true hybrid eyes to the general public for the first time, then she asks another character, Niall, what she looks like. Niall smiles and quotes a snippet of La Belle Dame sans Merci and gives Keats credit for his words.

References

- ↑ Dana M. Symons (2004), "La Belle Dame sans Mercy – Introduction", Chaucerian Dream Visions and Complaints, Medieval Institute Publications

- ↑ Kelvin Everest, John Keats, Northcotte House Publishers, 2002, p.86.

- ↑ "The Quietus". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |