Kyshtym disaster

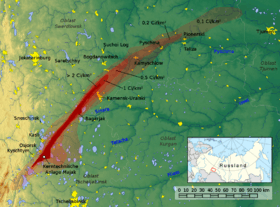

Map (in German) of the East Urals Radioactive Trace (EURT): area contaminated by the Kyshtym disaster. | |

| Date | 29 September 1957 |

|---|---|

| Location | Mayak, Ozyorsk, Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia |

| Coordinates | 55°42′45″N 60°50′53″E / 55.71250°N 60.84806°E |

| Type | Nuclear Accident |

| Outcome | INES Level 6 (serious accident) |

| Casualties | |

| 66 diagnosed cases of chronic radiation syndrome | |

| Estimated 200 additional cases of cancer | |

| 10,000 evacuated | |

The Kyshtym Disaster was a radioactive contamination accident that occurred on 29 September 1957 at Mayak, a plutonium production site in Russia for nuclear weapons and nuclear fuel reprocessing plant of the Soviet Union. It measured as a Level 6 disaster on the International Nuclear Event Scale (INES),[1] making it the third-most serious nuclear accident ever recorded, behind the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster and the Chernobyl disaster (both Level 7 on the INES). The event occurred in Ozyorsk, Chelyabinsk Oblast, a closed city built around the Mayak plant, and spread hot particles over more than 20,000 square miles (52,000 km2), where at least 270,000 people lived.[2] Since Ozyorsk/Mayak (named Chelyabinsk-40, then Chelyabinsk-65, until 1994) was not marked on maps, the disaster was named after Kyshtym, the nearest known town.

Background

After World War II, the Soviet Union lagged behind the US in development of nuclear weapons, so it started a rapid research and development program to produce a sufficient amount of weapons-grade uranium and plutonium. The Mayak plant was built in haste between 1945 and 1948. Gaps in physicists' knowledge about nuclear physics at the time made it difficult to judge the safety of many decisions. Environmental concerns were not taken seriously during the early development stage. Initially Mayak was dumping high-level radioactive waste into a nearby river, which flowed to the river Ob, flowing further down to the Arctic Ocean. All six reactors were on Lake Kyzyltash and used an open-cycle cooling system, discharging contaminated water directly back into the lake.[3] When Lake Kyzyltash quickly became contaminated, Lake Karachay was used for open-air storage, keeping the contamination a slight distance from the reactors but soon making Lake Karachay the "most-polluted spot on Earth".[4][5][6]

A storage facility for liquid nuclear waste was added around 1953. It consisted of steel tanks mounted in a concrete base, 8.2 meters (27 ft) underground. Because of the high level of radioactivity, the waste was heating itself through decay heat (though a chain reaction was not possible). For that reason, a cooler was built around each bank, containing 20 tanks. Facilities for monitoring operation of the coolers and the content of the tanks were inadequate.[7]

Explosion

In 1957 the cooling system in one of the tanks containing about 70–80 tons of liquid radioactive waste failed and was not repaired. The temperature in it started to rise, resulting in evaporation and a chemical explosion of the dried waste, consisting mainly of ammonium nitrate and acetates (see ammonium nitrate/fuel oil bomb). The explosion, on 29 September 1957, estimated to have a force of about 70–100 tons of TNT,[8] threw the 160-ton concrete lid into the air.[7] There were no immediate casualties as a result of the explosion, but it released an estimated 20 MCi (800 PBq) of radioactivity. Most of this contamination settled out near the site of the accident and contributed to the pollution of the Techa River, but a plume containing 2 MCi (80 PBq) of radionuclides spread out over hundreds of kilometers.[9] Previously contaminated areas within the affected area include the Techa river, which had previously received 2.75 MCi (100 PBq) of deliberately dumped waste, and Lake Karachay, which had received 120 MCi (4,000 PBq).[6]

In the next 10 to 11 hours, the radioactive cloud moved towards the north-east, reaching 300–350 km (190–220 mi) from the accident. The fallout of the cloud resulted in a long-term contamination of an area of more than 800 to 20,000 km2 (310 to 7,720 sq mi), depending on what contamination level is considered significant, primarily with caesium-137 and strontium-90.[6] This area is usually referred to as the East-Ural Radioactive Trace (EURT).[10]

Evacuations

At least 22 villages were exposed to radiation from the disaster, with a total population of around 10,000 people evacuated. Some were evacuated after a week, but it took almost 2 years for evacuations to occur at other sites.[11]

| Village | Population | Evacuation time (days) | Mean effective dose equivalent (mSv) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berdyanish | 421 | 7–17 | 520 |

| Satlykovo | 219 | 7–14 | 520 |

| Galikayevo | 329 | 7–14 | 520 |

| Rus. Karabolka | 458 | 250 | 440 |

| Alabuga | 486 | 255 | 120 |

| Yugo-Konevo | 2,045 | 250 | 120 |

| Gorny | 472 | 250 | 120 |

| Igish | 223 | 250 | 120 |

| Troshkovo | 81 | 250 | 120 |

| Boyovka | 573 | 330 | 40 |

| Melnikovo | 183 | 330 | 40 |

| Fadino | 266 | 330 | 40 |

| Gusevo | 331 | 330 | 40 |

| Mal. Shaburovo | 75 | 330 | 40 |

| Skorinovo | 170 | 330 | 40 |

| Bryukhanovo | 89 | 330 | 40 |

| Krivosheino | 372 | 670 | 40 |

| Kozhakul | 631 | 670 | 40 |

| Tygish | 441 | 670 | 40 |

| Chetyrkino | 278 | 670 | 42 |

| Klyukino | 346 | 670 | 40 |

| Kirpichiki | 160 | 7–14 | 5 |

Aftermath

Because of the secrecy surrounding Mayak, the populations of affected areas were not initially informed of the accident. A week later (on 6 October 1957), an operation for evacuating 10,000 people from the affected area started, still without giving an explanation of the reasons for evacuation.

Vague reports of a "catastrophic accident" causing "radioactive fallout over the Soviet and many neighboring states" began appearing in the western press between 13 and 14 April 1958, and the first details emerged in the Viennese paper Die Presse on 17 March 1959.[12][13] But it was only in 1976 (18 years after) that Zhores Medvedev made the nature and extent of the disaster known to the world.[14][15] In the absence of verifiable information, exaggerated accounts of the disaster were given. People "grew hysterical with fear with the incidence of unknown 'mysterious' diseases breaking out. Victims were seen with skin 'sloughing off' their faces, hands and other exposed parts of their bodies."[16] Medvedev's description of the disaster in the New Scientist was initially derided by western nuclear industry sources, but the core of his story was soon confirmed by Professor Leo Tumerman, former head of the Biophysics Laboratory at the Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology in Moscow.[17]

The true number of fatalities remains uncertain because radiation-induced cancer is clinically indistinguishable from any other cancer, and its incidence rate can only be measured through epidemiological studies. One book claims that "in 1992, a study conducted by the Institute of Biophysics at the former Soviet Health Ministry in Chelyabinsk found that 8,015 people had died within the preceding 32 years as a result of the accident."[3] By contrast, only 6,000 death certificates have been found for residents of the Techa riverside between 1950 and 1982 from all causes of death,[18] though perhaps the Soviet study considered a larger geographic area affected by the airborne plume. The most commonly quoted estimate is 200 deaths due to cancer, but the origin of this number is not clear. More-recent epidemiological studies suggest that around 49 to 55 cancer deaths among riverside residents can be associated to radiation exposure.[18] This would include the effects of all radioactive releases into the river, 98% of which happened long before the 1957 accident, but it would not include the effects of the airborne plume that was carried north-east.[19] The area closest to the accident produced 66 diagnosed cases of chronic radiation syndrome, providing the bulk of the data about this condition.[20]

To reduce the spread of radioactive contamination after the accident, contaminated soil was excavated and stockpiled in fenced enclosures that were called "graveyards of the earth".[21] The Soviet government in 1968 disguised the EURT area by creating the East Ural Nature Reserve, which prohibited any unauthorised access to the affected area.

According to Gyorgy,[22] who invoked the Freedom of Information Act to gain access to the relevant Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) files, the CIA had known of the 1957 Mayak accident since 1959, but kept it secret to prevent adverse consequences for the fledgling American nuclear industry.[23] Starting in 1989 the Soviet government gradually declassified documents pertaining to the disaster.[24][25]

Current situation

The level of radiation in Ozyorsk itself, at about 0.1 mSv a year,[26] is harmless, but the area of the EURT is still heavily contaminated with radioactivity.[19]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Lollino et al. 2014, p. 192

- ↑ Webb, Grayson (12 Nov 2015). "The Kyshtym Disaster: The Largest Nuclear Disaster You've Never Heard Of". Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- 1 2 Schlager 1994

- ↑ Lenssen, "Nuclear Waste: The Problem that Won't Go Away", Worldwatch Institute, Washington, D.C., 1991: 15.

- ↑ Andrea Pelleschi (2013). Russia. ABDO Publishing Company. ISBN 9781614808787.

- 1 2 3 "Chelyabinsk-65".

- 1 2 "Conclusions of government commission" (in Russian).

- ↑ "Kyshtym disaster | Causes, Concealment, Revelation, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-11-26.

- ↑ Kabakchi & Putilov 1995, pp. 46–50

- ↑ Dicus 1997

- ↑ Kostyuchenko & Krestinina 1994, pp. 119–125

- ↑ Soran & Stillman 1982

- ↑ John Barry; E. Gene Frankland (25 February 2014). International Encyclopedia of Environmental Politics. Routledge. p. 297. ISBN 978-1-135-55396-8.

- ↑ Medvedev 1976, pp. 264-7

- ↑ Medvedev 1980

- ↑ Pollock 1978

- ↑ "The Nuclear Disaster They Didn't Want To Tell You About". Andrews Cockburn. Esquire Magazine. 26 April 1978.

- 1 2 Standring 2009, pp. 174–199

- 1 2 Kellerer 2002, pp. 307–316

- ↑ Gusev, Gusʹkova & Mettler 2001, pp. 15–29

- ↑ Trabalka 1979

- ↑ Gyorgy 1979

- ↑ Newtan 2007, pp. 237–240

- ↑ "The decision of Nikipelov Commission" (in Russian).

- ↑ Smith 1989

- ↑ Suslova, KG; Romanov, SA; Efimov, AV; Sokolova, AB; Sneve, M; Smith, G (2015). "Journal of Radiological Protection, December 2015, pp. 789-818". J Radiol Prot. 35 (4): 789–818. doi:10.1088/0952-4746/35/4/789. PMID 26485118.

References

- Lollino, Giorgio; Arattano, Massimo; Giardino, Marco; Oliveira, Ricardo; Silvia, Peppoloni, eds. (2014). Engineering Geology for Society and Territory: Education, professional ethics and public recognition of engineering geology, Volume 7. International Association for Engineering Geology and the Environment (IAEG). International Congress. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-09303-1.

- Schlager, Neil (1994). When Technology Fails. Detroit: Gale Research. ISBN 978-0-8103-8908-3.

- Kabakchi, S. A.; Putilov, A. V. (January 1995). "Data Analysis and Physicochemical Modeling of the Radiation Accident in the Southern Urals in 1957". Moscow ATOMNAYA ENERGIYA (1). Archived from the original on 3 April 2015.

- Dicus, Greta Joy (16 January 1997). "Joint American-Russian Radiation Health Effects Research". United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- Kostyuchenko, V.A.; Krestinina, L.Yu. (1994). "Long-term irradiation effects in the population evacuated from the East-Urals radioactive trace area". Science of the Total Environment. 142 (1–2): 119–25. doi:10.1016/0048-9697(94)90080-9. PMID 8178130. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- Medvedev, Zhores A. (4 November 1976), Two Decades of Dissidence, New Scientist

- Medvedev, Zhores A. (1980), Nuclear disaster in the Urals translated by George Saunders. 1st Vintage Books ed, New York: Vintage Books, ISBN 978-0-394-74445-2 (c1979)

- Soran, Diane M.; Stillman, Danny B. (1982). An Analysis of the Alleged Kyshtym Disaster. Los Alamos National Laboratory. doi:10.2172/5254763.

- Pollock, Richard (1978). "Soviets Experience Nuclear Accident". Critical Mass Journal.

- Standring, William J.F.; Dowdall, Mark; Strand, Per (2009). "Overview of Dose Assessment Developments and the Health of Riverside Residents Close to the "Mayak" PA Facilities, Russia". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 6 (1): 174–199. doi:10.3390/ijerph6010174. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 2672329. PMID 19440276. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- Kellerer, AM. (2002). "The Southern Urals radiation studies. A reappraisal of the current status". Radiation and Environmental Biophysics. 41 (4): 307–16. doi:10.1007/s00411-002-0168-1. ISSN 0301-634X. PMID 12541078.

- Gusev, Igor A.; Gusʹkova, Angelina Konstantinovna; Mettler, Fred Albert (28 March 2001). Medical Management of Radiation Accidents. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-7004-5. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- Trabalka, John R. (1979), Russian Experience (PDF) pp. 3–8 in Environmental Decontamination: Proceedings of the Workshop, 4–5 December 1979, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, CONF-791234

- Gyorgy, A. (1979). No Nukes: Everyone's Guide to Nuclear Power. ISBN 978-0-919618-95-4.

- Newtan, Samuel Upton (2007), Nuclear War I and Other Major Nuclear Disasters of the 20th century, ISBN 9781425985127

- Smith, R. Jeffrey (10 July 1989). "Soviets Tell About Nuclear Plant Disaster; 1957 Reactor Mishap May Be Worst Ever". The Washington Post: A1.

- Rabl, Thomas (2012), The Nuclear Disaster of Kyshtym 1957 and the Politics of the Cold War." Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia 2012, no. 20. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society.

External links

- Focus on the 60th anniversary of the Kyshtym Accident and the Windscale Fire

- An Analysis of the alleged Kyshtym Disaster

- Der nukleare Archipel (in German)

- Official documents pertaining to the disaster (in Russian)